By Rachel Dickson

It is no coincidence that we refer to the ‘making’ of a drawing. To draw is to make and to make is to draw. To draw on skills, experience, material qualities, the past, a glimpse of the future and the influence of others. Others who have taught us, told us their stories, showed us their secrets and entrusted us to pass them on. Others we have never met.

How do we learn to explore our stories through material and line. Is this a skill developed by chance, by coincidence, through the influence of other ‘drawings’, by experimentation, or being directed. In all cases, the link between the head and hand unfolds through the ‘drawing’. The hand often answers many questions that the mind or sketch cannot, and there may also be lessons to be learned of trust. A trust in the ability of the artist/maker, and experience stored that is somehow remembered through the hand.

Drawing can be viewed as preparatory thought, conversation or exchange. Sometimes never revealed, it becomes the secret held by the artist, utilised to produce the more cohesive, final, concluded work. Somehow, this hidden process can appear the most interesting and thought provoking element in that line from idea to object (whether this is ceramic, painting or print).

Makers will employ a range of drawing techniques in their particular practice. It can often become revelatory to ‘peek behind the curtain’ and explore the decision-making process used, through the making of marks, thoughts, maquettes, material tests, and drawing in space. Some ceramicists will only see drawing as the plan on a page, which leads to the construction of a material object. Others will explore a line using altered or found materials, which then manifests itself in space. Others use clay, glaze, oxide as basic drawing material, substituting these from pencil and ink.

Drawing in these terms, lends itself to analysis and exploration and, therefore, becomes linked with integrity and honesty. In contemporary practice, drawing/making can no longer be seen as secondary or confined to the margins. Looking, seeing, thinking, making, are all vital and fundamental elements of the conveying of ideas. By viewing works in clay as works of drawing and process, these objects seek to encourage and enlighten us.

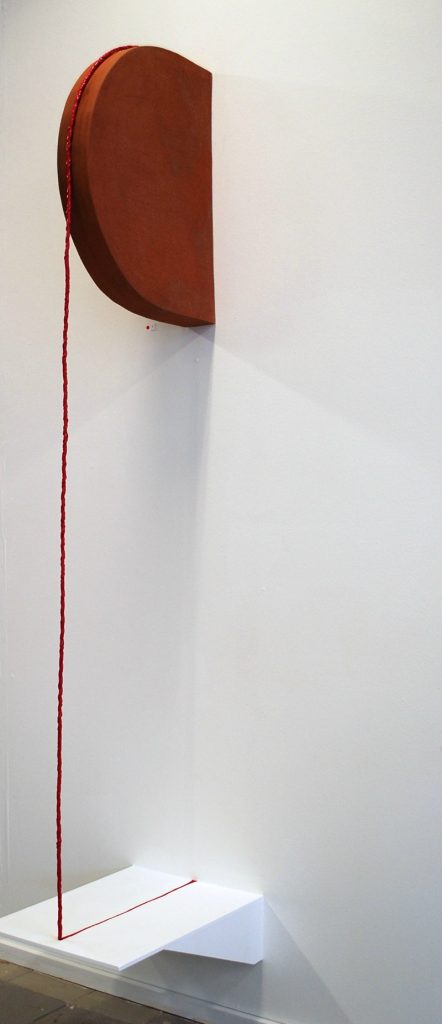

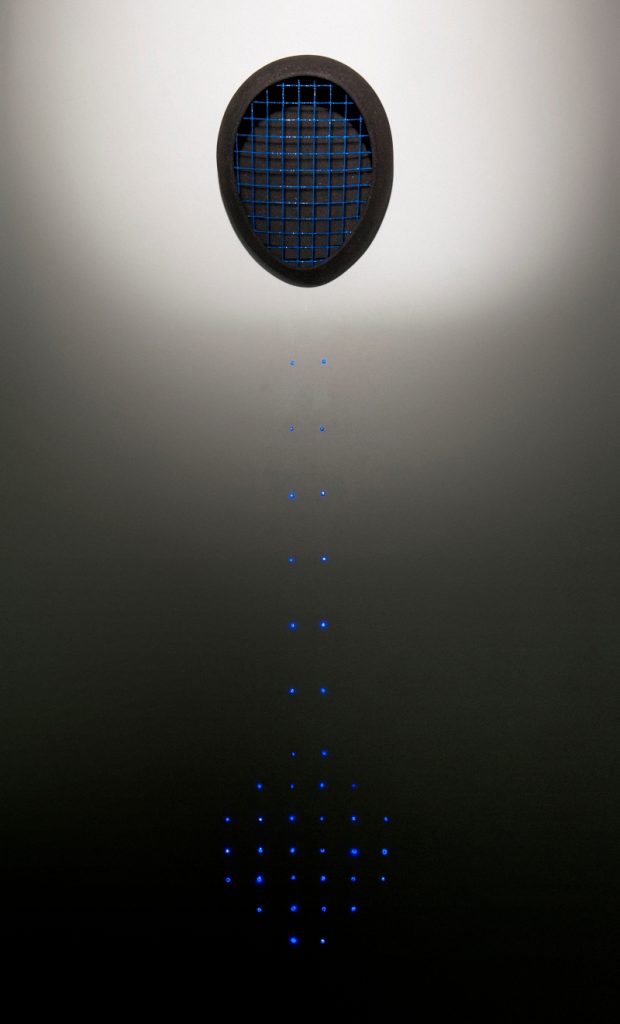

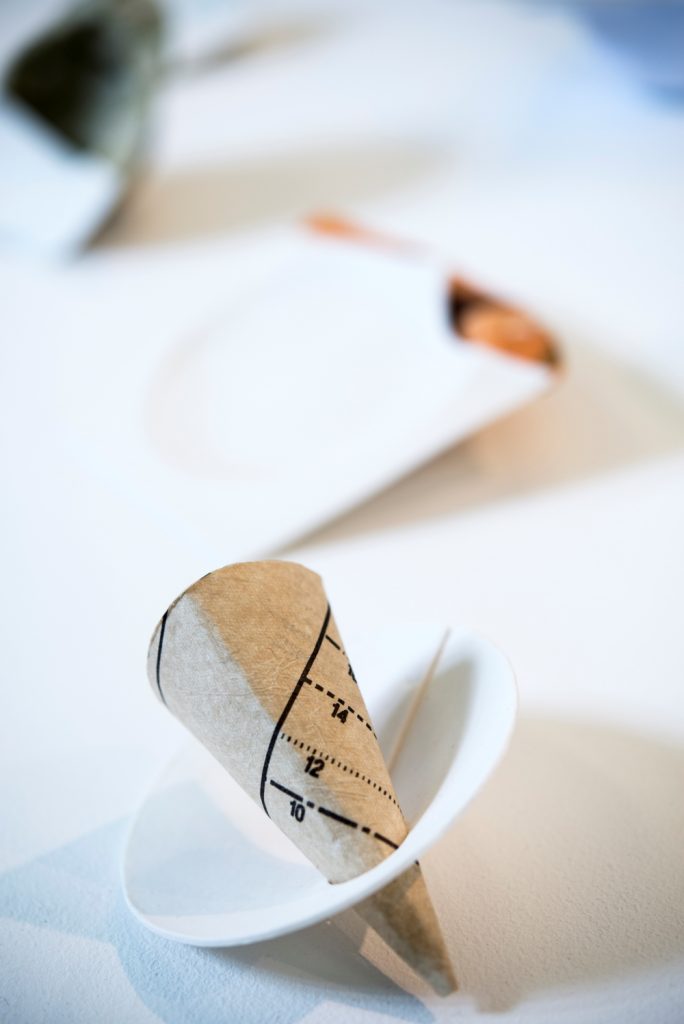

Rachel Dickson, to make: to remake, 2014, Porcelain paperclay, paper, found ceramic. Photo by Glenn Norwood.

Rachel Dickson, to make: to remake (detail), 2014, Porcelain paperclay, paper, found ceramic. Photo by Glenn Norwood.

Rachel Dickson, to make: to remake, 2014, Porcelain paperclay, paper, found ceramic. Photo by Glenn Norwood.

When it is possible, we are privileged to experience the drawing process, in its broadest terms, of makers. As a course director and lecturer in contemporary applied arts, I am lucky to witness such exploration and experimentation amongst ceramics students seeking out ways to develop and enhance their work in clay. It is also interesting and perhaps significant in contemporary practice that many of these new makers have embraced technology in the ‘drawing’ or ‘construction’ of their work. There is a sense of the machine, a use of technology that is both skilful and appropriate, yet does not appear to overpower the hand. To relinquish control of making seems to be the antithesis of craft, yet many contemporary makers are employing industrial techniques or using appropriated objects in order to explore further, the line between head and hand. The question may arise as to the level of craft which remains in these final works.

The incorporation of industrial processes cannot be disregarded within the realm of ceramics. The importance is in an understanding of the process. The artist should have knowledge of the ‘how’, in order to understand and exploit the possibilities. Is it not crucial that there appears a sense of investigation, a seeking out, an experimentation, and a respectful approach to both the context and the material. We cannot be afraid of the ‘drawing’ of works through a 3D printer, just as we embraced the technology of an electric wheel or industrial slip-casting techniques.

The fascination exists in the knowledge that these makers have the ability and responsibility to produce works, which take up space in the world, in whichever processes they have chosen to create ceramic objects. Some works are fleeting, momentary, projected, glimpsed, made from dust. Others are more permanent, existing in the context of their environment. Added layers exist in the revealing of the drawing, in the construction of an idea and the process of drawing it out into an object.

Courage can be sought in the revealing of the artist’s own drawing process, an honesty in the making, in whichever process this may be, and an integrity of context. The objects and works produced seek to reveal what can be ‘drawn’ from this.

Rachel Dickson is a graduate of the Royal College of Art and is currently Associate Head of School of Belfast School of Art, Ulster University. As a practicing maker, research interests explore ideas of memory, the narrative of objects, and the space between art and craft, to include the possibilities of digital fabrication and the handmade. She is a Director of CraftNI, a member of Applied Arts Ulster, and ICE: Irish Ceramic Educators.

Visit Rachel Dickson’s website.

2014. Article published in Ceramics Now Magazine, Issue 3.