By Lilianne Milgrom

Irit Ovadia Rosenberg would be the first to tell you that she never imagined establishing a ceramic practice amongst the towering pines of New York State’s Catskills mountains, far from the madding crowd of her native New York City. Nestled between the conifers and surrounded by wild fern, her studio barn and cottage gallery provide a serene backdrop that lend her substantive, tactile assemblages an even greater sense of expanded space and time.

In her latest assemblage series, the artist hangs draped ceramic forms alongside the brutalist, rusted remains of farm machinery from bygone days, creating an uneasy yet harmonious co-existence. I sat down with Irit to discuss the nature and evolution of these unique groupings.

Let’s start with your ceramic oeuvre. Both your functional and sculptural forms have always been defined by a conscious desire to show the creator’s hand and celebrate the imperfect – you embrace the cracks, the runny glazes and even the warping!

I’ve always enjoyed bending the rules and seeing how far I can go in manipulating the clay. That’s probably why I prefer hand building to wheel throwing. I love the infinite possibilities of a freshly rolled slab. I get so much enjoyment texturizing and printing on slabs even before shaping them into a form. I think the lack of formal training allowed me to experiment with clay from the very beginning. I sort of fell into ceramics while I was teaching art at the American School in Israel. The school wanted to offer a clay elective and aside from some rudimentary training, I learned about clay as I went along. The purist, pristine aesthetic never appealed to me. Some of my failed experiments were my favorite pieces!

You have accumulated decades worth of experimental ceramic fragments as well as components from past series and exhibitions. What inspired you to re-purpose these items and combine them with pieces from your ever-expanding collection of rusted metal and weathered wood artifacts?

Those ceramic pieces still hold meaning for me – they were created with my own hands. They represent a point along the continuum of my ceramic education. I find many of them beautiful and want to give them a new home, a new lease on life, if you will. It’s like sending your kid out into the world again! I enjoy the symbolic transformation of a solitary, random object when it becomes part of a bigger picture. Similarly, I’m drawn to old scavenged and found objects because of their history. They are also deserving of a second chance. Aesthetically, the build up of rust and texture on these corroded objects are reminiscent of the iron oxide and iron glazes I am fond of using. I like the fact that even though my hand built ceramic pieces are vulnerable to breakage, the clay fragments may well last longer than the machinery-produced elements. The rusted artifacts scream ‘Don’t touch’ whereas the smooth surfaces of my draped ceramics are an invitation to caress. There’s a dialogue that develops between the discordant elements – sometimes it’s loud and sometimes it’s quiet.

What is the origin and significance of your draped forms? Is there a story behind them?

Years ago, I was visiting a museum in New York and I was struck by the expressive folds of the garments on the Greek and Roman sculptures. Fabric is an integral part of human civilization and plays a significant role in all aspects of our lives – from the soft fabric you swaddle a baby in, to the sheet that one is buried in according to Jewish tradition. But creating a facsimile of draped fabric out of clay is extremely challenging. I usually start out with texturizing or silkscreen printing on a slab before carefully forming the folds and letting the piece dry very, very slowly. During the firing (cone 10), the piece has to lie flat in the kiln so unfortunately I often lose the fullness of the folds and they develop cracks as they sag. Even allowing for imperfections, my breakage rate for these draped forms is about sixty percent!

I arrange and re-arrange constantly – I can very much relate to Oscar Wilde’s famous quote: “I spent all morning taking out a comma and all afternoon putting it back!” I get a distinct feeling in my gut when the piece comes together in a harmonious composition. Like the pieces of a puzzle.

Walk me through your assemblage process – do you begin with one foundational piece that sets the tone for each assemblage? How do you know when they are complete?

I’ve loved the art of assemblage ever since being introduced to Picasso’s early assemblages. Jasper Johns is also a great inspiration. I usually start from the top down with the horizontal element that will support the hanging components. I get excited when I find a piece that is full of character and interesting detail. I hang it on a blank wall of my gallery and then I start picking through my collection of ceramic works and metal or wooden objects. I customize the hanging hardware either out of old chain or twisted wires. It’s a very physical process and one that is painstakingly slow. I arrange and re-arrange constantly – I can very much relate to Oscar Wilde’s famous quote: “I spent all morning taking out a comma and all afternoon putting it back!” I get a distinct feeling in my gut when the piece comes together in a harmonious composition. Like the pieces of a puzzle. It’s a great feeling but I might come back to it weeks later and start substituting or adding elements. I consider these assemblages as works in progress.

Could you see creating these assemblages without ceramics?

I can’t imagine not using some element made of clay in my work. Clay is such a remarkable material. Working with clay engages the four elements of matter: Earth, Water, Air and Fire. The ceramic pieces play off the found objects in terms of material, texture, history and design.

How has moving out of the city to the country impacted your work?

It was a difficult transition. When I lived in New York City I had access to some of the most innovative art being produced. I worried at first about what I was missing out on but now I appreciate the quiet and serenity of the Catskills and its history as an agricultural community. I source almost all of my found objects from this area. I think my love of forgotten and abandoned farm implements stems from my time in Israel, a country so ancient that you need only scratch the dirt to find a two-thousand-year-old shard of pottery!

What do you want the viewer to take away from these mixed media assemblages? Do you have a message?

I don’t create my assemblages with a particular concept in mind. I am more focused on the relationship between the disparate elements and creating a balanced harmony. I create them primarily for myself and when they’re ready to be seen, they can act as repositories for any number of meanings. Aside from wanting my viewers to appreciate the tactile and visual nature of the works, I urge them to question and to find their own narrative. I love that art is open for interpretation.

Irit Rosenberg

Irit Ovadia Rosenberg was born in Israel and raised in the US. She studied at Jerusalem’s Bezalel School of Art and Design and earned her undergraduate degrees in art from New York’s School of Visual Art and Hunter College. She taught Art and Ceramics at the American International School from 1994 to 2014. She currently lives in upstate New York with her husband.

When living and working in Israel she was inspired to explore the controversial issue of fences, walls and borders. It was then that she began incorporating found objects and corroded metal fragments. Her mixed media works form a sculpture of many voices. She draws inspiration from clay, its versatility, its texture and its amazing transformations.

Visit Irit Rosenberg’s website and Instagram page.

Lilianne Milgrom

Lilianne Milgrom is a multimedia artist, ceramicist and published author. Her articles have appeared in Ceramics Now, Ceramics Monthly and Ceramics Art and Perception.

You can see Lilianne’s artwork on her website or Instagram page and find out more about her writing here.

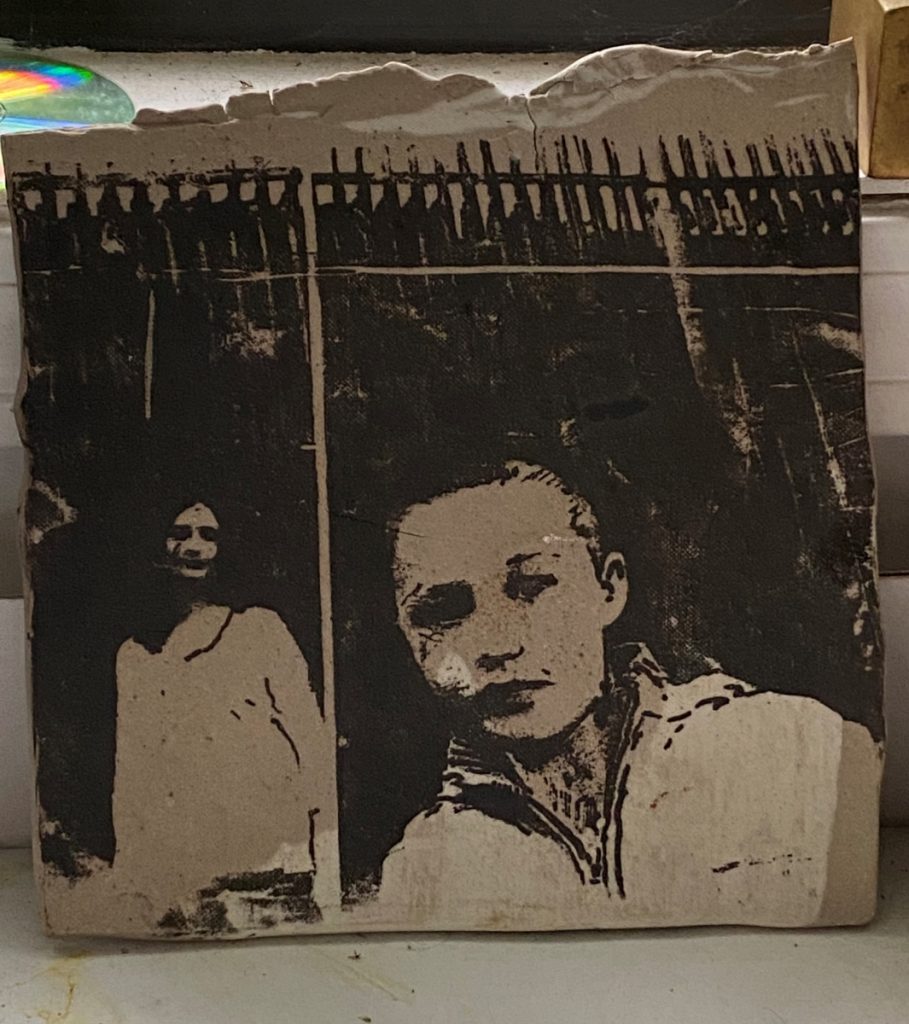

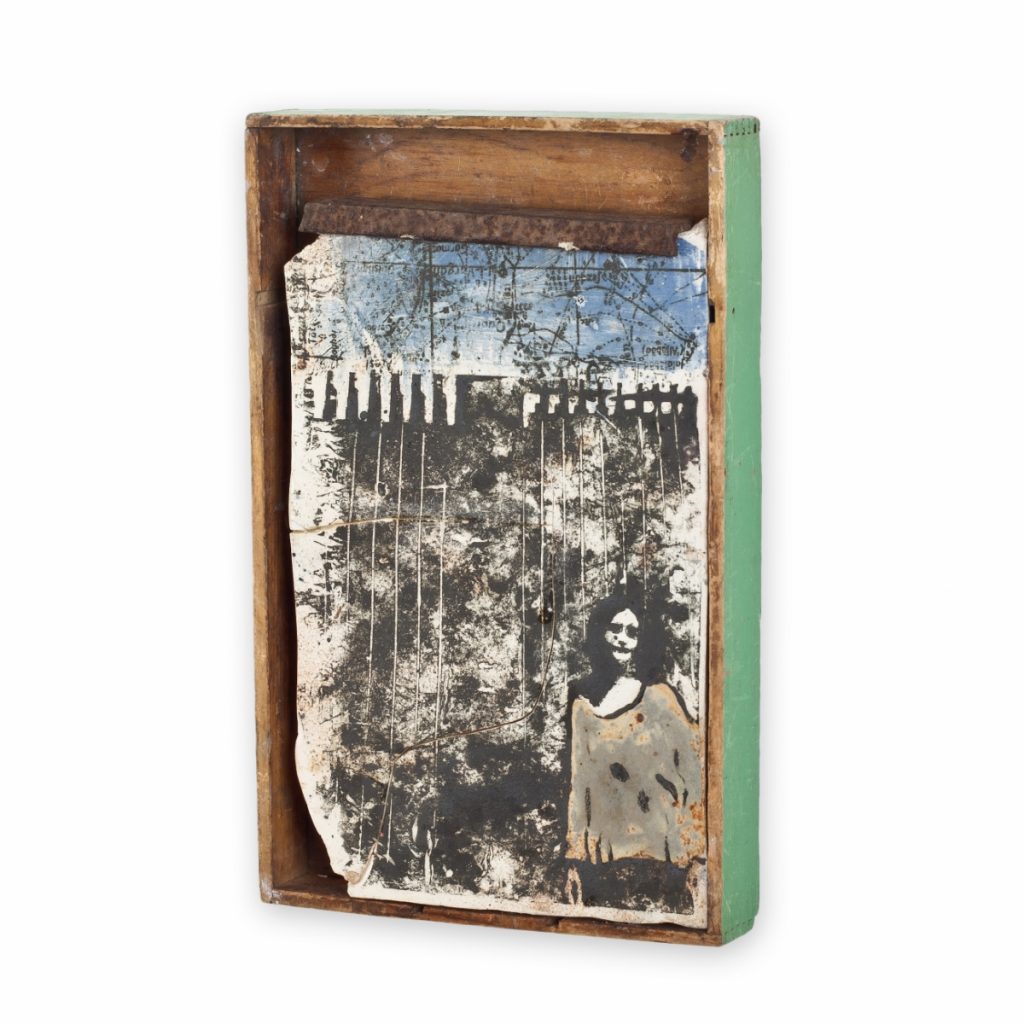

Photo captions

- Boxed woman, High Fired Stoneware, silkscreen, found materials, 21x15x3

- Korea, High Fired Stoneware, silkscreened, found materials, 11x6x5

- Mapped Fence, High Fired Stoneware, silkscreened, found materials, 22x22x3

- Mother and Son, High Fired Stoneware, silkscreen, found objects, 20x17x

- Platter, High fired stoneware, silkscreen, 24

- Woman Alone, High Fired Stoneware, silkscreen, found objects, 24x22x3

Comments 1