Kamer vol klei is on view at Museum Albert Van Dyck, Schilde

February 28 – June 4, 2023

Kamer vol klei translates as Room full of clay

Essay by Liesbet Waegemans

‘We should be grateful that we have sufficient food. Which is why we have to treat it with a great deal of respect. Nothing is too good or too beautiful to prepare or serve food in. The food nature gives us deserves appreciation. The plate that is designed with love and made by hard work is also meant to honour that which is laid on it.’1

The words of Piet Stockmans, in whose work the plate recurs as both a utensil and an archetype, neatly summarises my own fascination with ceramics: it represents people’s connection with the earth. A connection in which the earth is not just utilised, but also loved and cherished. As a receptacle, the plate is the ultimate object and symbol of this link. So are the bowl and the vase. Critic and curator Dieter Roelstrate argues: ‘The fact that so much recent interest in ceramics as a contemporary art form has revolved around the archetype of the pot in particular (bowls, jugs, vases: vessels) is shaped in no small part by this archetype’s symbolic force as a gathering site, as a metaphor for assembling and convening.’2 The receptacle also opened up a fresh perspective on communal living for writer Ursula K. Le Guin. Her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction was inspired by anthropologist Helen Fisher’s theory that people made receptacles—the carrier bag, the net, the bowl for gathering food—before they invented spears. Le Guin wants to rewrite the history of civilisation from a radical perspective. She seeks to replace the centuries-old canonical stories, in which heroic warriors subjugate nature with their weapons, with new narratives based on communion—around a bowl, for example—and a shared existence. I like to think that the artists referred to by Dieter Roelstrate, who repeat the primal act of making a bowl, are standing at the dawn of civilisation once more. And creating a new world.

Last year, the Museum Albert Van Dyck in Schilde (Belgium) invited me to curate an exhibition on ceramics as an art form. The starting point is the emergence of the genre in the 1950s, with a focus on the first and second generation of artists who forged their careers at this time. People’s relationship with the earth became a key focal point of the resulting exhibition. This is not only expressed through objects, however. Clay lends itself to the theme more than any other medium. Clay is earth. Artists bring the clay itself into focus, and the relationship with the earth becomes tangible.

Until recently, the term ‘ceramics’ has denoted work in fired clay, both in pottery and within the realm of ceramics as an art form. ‘Ceramics’ is derived from the Greek word keramos, which means ‘fired pot’. Yet the notion of what ceramics are and can be is expanding to include work in unfired clay. The exhibition Kamer vol klei and the accompanying publication Hands, Eyes, Ceramics aim to bring this diversity to the fore. A diversity in which installation, photography and video all find their place alongside sculpture.

Ceramic art has always suffered from its association with the applied arts, within which the manufacture of utilitarian objects is paramount. Moreover, the status of clay as a medium, supposedly less noble than bronze or silver, means that ceramics have long been considered inferior within the fine arts. This has changed in the past decade. Ceramics have been embraced by the visual arts like never before and are now omni-present at art manifestations, art fairs and biennales. And at the Museum Albert Van Dyck.

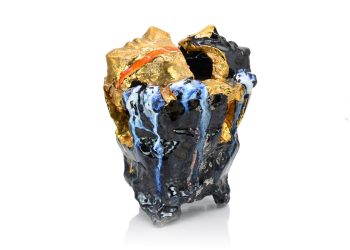

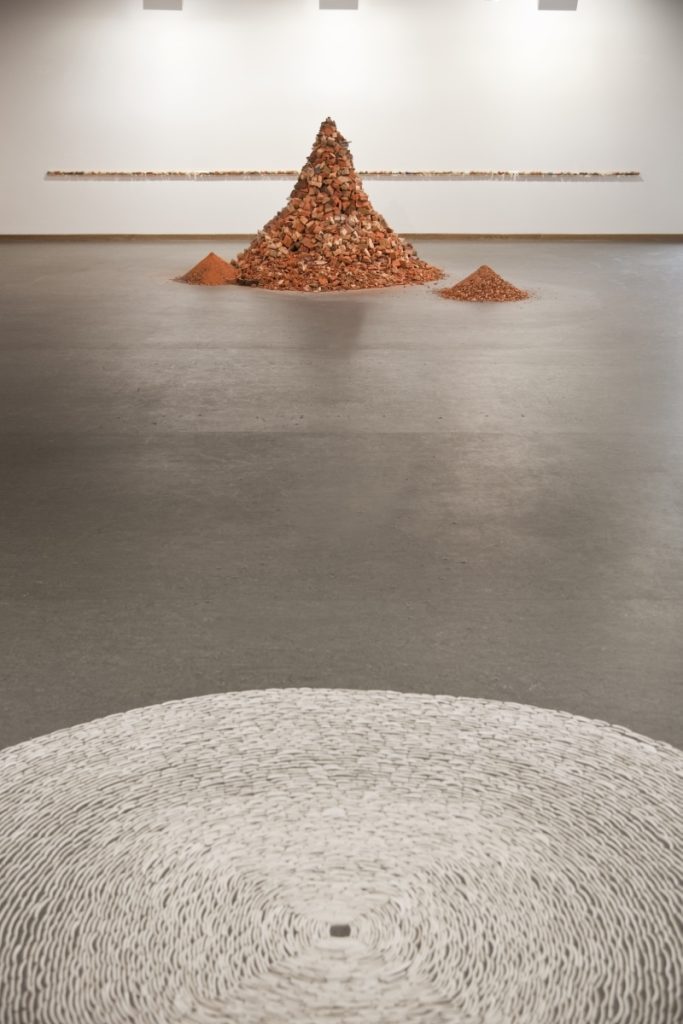

Kamer vol klei presents the work of Rogier Vandeweghe, Pierre Culot, Lutgart De Meyer, José Vermeersch, Nathalie Doyen, Anne Ausloos, Alexandra Engelfriet and Bie Michels. The vase is the starting point of the exhibition. It occupies an important place in the work of Rogier Vandeweghe (1923-2020), one of the first ceramists in Belgium to elevate pottery to a higher level in the 1950s. His vases have a sculptural character, not least because of their scale—some are two metres high—but also because of their infinitely elaborate forms wherein nothing is too much or too little. Pierre Culot (1938-2011) was another innovator in the field of pottery. His early tableware pieces rapidly evolved into a sculptural oeuvre, culminating in his iconic and enigmatic torso-shaped vases that evoke the human figure. In his work, which evolved towards land art over the years to become part of nature, the form of the pot remained the key reference. ‘I refuse abstraction, forms that cannot contain’, says Culot. The vase, or enveloping form, remains tangible even in Lutgart De Meyer’s (1924) final ceramic pieces, which clearly express a desire to let go: the folded forms reveal buckling, cracks and fissures. That the vase is not a static object becomes even clearer in the work of Nathalie Doyen (1964). She smashes bowls and vases, and uses the shards to create installations. The artist says: ‘From the fragments, something new emerges. An image as strong as that of the vase. One that brings the inside and the outside together.’ Anne Ausloos (1954) pulverised all the ceramics still in her possession from the period 1972 to 1991. She wants to eventually return the particles to the all-encompassing geological cycle. Ausloos works like an artist-researcher. In In a Lifetime Exploration, her contribution to Kamer vol klei, she explores the physical characteristics of the particles, resulting in installations and a film. Materiality is also central to the work of Alexandra Engelfriet (1959). The experience of the clay is her primary concern. She multiplies its pleasing sensation between the fingers—which largely explains the popularity of ceramics in these digital times. She delves into the material with her whole body, using video as the medium of choice to capture this transformative experience. The body descends into the earth and re-emerges. In this case, the clay is both matter and metaphor. This is also true of Bie Michels’ (1960) work. Her video’s around the vase and the brick—that other essential form within ceramics—is shown alongside her ceramic drawings, for which she smeared her body with red brick dust. The ascending figures that can be discerned have a symbolic value. Cyclical movement can also be detected in the work of José Vermeersch (1922-1997). With his earth-coloured figures, depicting humans and dogs, he seems to be searching for an existential state that precedes life, that knows no difference between man and animal, between man and woman. That primal state transcends the limitations of society and situates humanity within a greater whole.

Taking the works in Kamer vol klei as a starting point, the accompanying publication Hands, Eyes, Ceramics outlines the practices of the participating artists and the broader context within which they either developed or are currently working. Kamer vol klei starts in the 1950s, the era in which ceramics underwent a fundamental renewal on the world stage. Artists from Pablo Picasso to Joan Miró and Lucio Fontana discovered the medium. On the one hand, the art of ceramics reinvented itself and acquired a broader and more modern interpretation; on the other hand, and above all else, ceramics developed into a new artistic medium within the fine arts, with both figurative and abstract iterations.

Through the introduction of colour, ceramics made a fundamental contribution to the monochrome world of sculpture. Different hues are typically applied to clay using glazes or engobes. But ceramics also introduced a sense of playfulness. Art critic Lisa Ponti, for instance, argued in 1948 that sculpture was ‘over’, in crisis, and that ceramics provided ‘a florescence of the baroque, provisional, capricious’.3

Henry Van de Velde, one of the pioneers of modernism who advocated the integration of arts and crafts, played a crucial role in the development of ceramics in Belgium. Noticing that the country was lagging behind, he launched the first ceramics course in 1937 at the Higher Institute for Architecture and Applied Arts in Brussels, where he aimed to put his theories into practice. He encouraged artists working in other disciplines to explore the medium. One of the most pre-eminent forerunners in this respect was Pierre Caille, who made colourful and fantastical sculptures inspired by folk art. He also taught at La Cambre, where his pupils included Antoine de Vinck, who became known for his austere forms influenced by the East, Jan Heylen, who created art brut-like figures, and Olivier Strebelle. The latter went on to head the ceramics department that opened at the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts in 1953. Strebelle subsequently taught Lutgart De Meyer, Louise Servaes, Jan Dries, Jef Verheyen and Jan Van de Kerckhove, who, like their tutor, mainly trod the path of geometric abstraction. The KASK in Ghent opened a ceramics department in 1955. Two of their first students were Roger Raveel who made playful abstract figurative work (resembling his paintings but in three dimensions) and Carmen Dionyse, who quickly found fame with her mythologically inspired busts and masks.

Such courses lacked the necessary professionalism during the early years. Yet they nevertheless offered a context and environment in which numerous artists could explore the medium. Just as many artists are apprenticed to one another, Rogier Vandeweghe honed his skills in the studio of Joost Maréchal, an innovator in pottery who also produced abstract work. Pierre Culot knocked on the doors of Antoine de Vinck and the grandmaster of British ceramics, Bernard Leach. Certain artists made the craft uniquely their own, as did José Vermeersch, for example.

The World’s Fair in Brussels, Expo 58, played an important role within the development of ceramics in Belgium. It placed the work of Carmen Dionyse, Jan Heylen, Antoine de Vinck and others on the map. A group of artists from Antwerp, who were not represented at Expo 58, then joined forces to create their own group, G58. They organised numerous exhibitions, including the work of Lutgart De Meyer, Louise Servaes, Jan Dries and Jef Verheyen. For the latter two makers, as well as Roger Raveel, ceramics proved to be a temporary diversion. For other artists, it became (one of) their principal discipline(s). As knowledge of the medium increased, cross-pollinations between artists also occurred, and exhibitions followed one another in quick succession. Institutions such as the PMMK in Ostend (now Mu.ZEE), the Museum of Decorative Arts in Ghent (now the Design Museum) and the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels all started to collect ceramics. Belgian makers also gained international recognition. Rogier Vandeweghe, Carmen Dionyse, Olivier Strebelle, Pierre Caille, Jan Van de Kerckhove and Antoine de Vinck, amongst others, all won prizes at the prestigious annual Concorso Internazionale Premio Faenza. José Vermeersch represented Belgium with his ceramic work at the Venice Biennale in 1983.

An important shift occurred in the 1970s. Within the visual arts in general, and within ceramics specifically, the object and classical modes of presentation diminished in significance. ‘A dissatisfaction with the current social and political system resulted in an unwillingness to produce commodities which gratify and perpetuate that system. Here the sphere of ethics and aesthetics merge’4, argued art critic Barbara Rose in 1969. Sculpture was deconstructed. It was removed from its pedestal and displayed in installations, either directly on the floor or suspended from on high. With his repetitive installations of often broken bowls and plates, Piet Stockmans was one of the pioneers. The artwork no longer thrived in classical museum and gallery contexts. With their land art projects, artists such as Anne Ausloos and Nathalie Doyen moved their work into nature. Their interventions are often ephemeral. Performance became the medium of choice for revealing the creative process, and also, especially in the case of ceramics, the experience of the material, as evidenced in the work of Alexandra Engelfriet and Bie Michels. They regularly involve the audience in the process. Such practices are documented, in particular, via photographs and videos. Beyond the object, the emphasis is on the material. ‘The focus of the 1970s environmental movement on the degradation of landscape through pollution and stripping of natural resources led to a particular stress in ceramics on the value of their own raw material the earth’5, explains Edmund de Waal. The wealth of stories that clay holds is made visible, and with it the preciousness of the earth. A beautiful example of this is Forced to Settle, the result of research by Anne Ausloos, which is reproduced on the cover of this publication.

Translation by Helen Simpson

Hand, Eyes, Ceramics, an illustrated publication with texts by Liesbet Waegemans, Lut Pill & Lottie Brown, was published in connection with the exhibition.

Contact

cultuur@schilde.be

Museum Albert Van Dyck

Brasschaatsebaan 30

Schilde, Antwerp

Belgium

Photos by Tom Van Hee

Footnotes

- Piet(er) Stockmans: een meesterlijk dilemma – a masterly dilemma, Genk: Pieter Stockmans Foundation, 2010, p. 67.

- José Vermeersch. Presences, Brussels: Ludion, 2022, p. 85.

- Vitamin C. Clay + Ceramic. In Contemporary Art, Phaidon Press, 2021, p. 12.

- E. de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics, New York – London: Thames & Hudson World of Art, 2003, p. 175-176.

- Ibid., p. 176.