By Dr Marte Johnslien, Associate Professor of Ceramic Art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, Norway

In June 2024, the Hidden Stone exhibition opened at Velferden in the south-west of Norway. It contained works by the research group TiO2: The Materiality of White (MoW), which the author of this article, Marte Johnslien, leads at the Department of Art and Craft, subject area Ceramics, at Oslo National Academy of the Arts in Norway1. The exhibition centers around the history of ilmenite mining to produce the world’s most used white pigment, titanium dioxide (TiO2). However, it also exemplifies how, as educators in ceramic art, we can navigate the increasingly significant yet sometimes conflicting roles of preserving craft knowledge and traditions while fostering a conscientious approach to the use of natural resources.

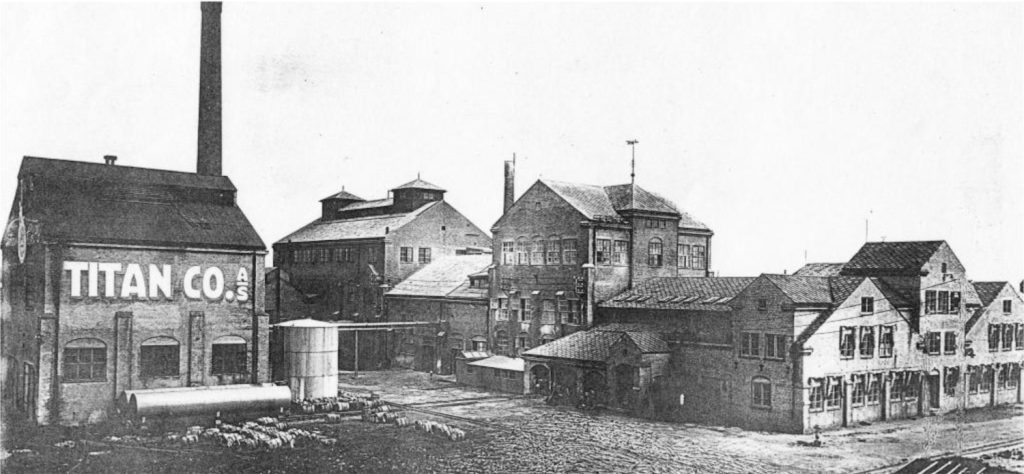

The exhibition took place in the former Welfare building of the mining company Titania AS, now run as an art space by Maiken Stene and Hans-Edward Hammonds. The MoW artist group delves into the industrial history of the white pigment, titanium dioxide. Developed from Sandbekk’s ilmenite ore, the first patented production of titanium dioxide in 1910 has been instrumental in shaping our modern world. Titanium dioxide white pigment is a global color phenomenon. Marketed as non-toxic, long-lasting, and chemically stable, the pigment replaced zinc white and lead white pigments in the 1920s, supporting the modernist vision of a bright future by becoming the primary colorant for paint, lacquer, paper, plastic, food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products in the following decades. In 2024, titanium dioxide is present in almost all man-made products and is the most produced color pigment of our time. The pigment is now found in most paint products and all white (or lightly colored) plastic objects and cosmetics. This includes sunscreen, make-up and tattoos. In some regions, the pigment is even added to candy, chocolate and other food products. It is safe to say that the invention of the production method of titanium dioxide by Norwegian chemists and industrialists Dr. Peder Farup and Dr. Gustav Jebsen has left a profound impact on the modern world.2

Fig. 2. The open-pit mine of Titania, Tellnes, Norway. Photo: Marte Johnslien.

This profound impact of titanium dioxide also extends below the surface. Titanium dioxide pigment seems to travel invisibly within our objects and systems. In my practice, I use the four elements of fire, air, water, and earth to conceptualize the trope of invisibility. White surfaces are primarily perceived by the human eye as devoid of content, and I believe they are interpreted as immaterial – akin to the element of air, rather than earth, where the material originates. Thus, one might say that titanium dioxide is a paradoxical substance – a metal oxide derived from minerals deep within the ground, yet with a presence that appears immaterial or even invisible. This paradox may have caused the public to overlook it as a material substance despite its ubiquity in visually defining our physical surroundings for over a century.3

The physical impact of the pigment is highly evident at the production sites of ilmenite, specifically at the mining company Titania AS and the pigment factory Kronos Titan AS4. At the mining facility in Tellnes, Sokndal, which has been operating since 1960, approximately 12% of the world’s ilmenite resource is found in a single, enormous ore deposit. Excavations of the open-pit mine leave behind a vast scar in the landscape, and the surrounding areas are littered with tailings from the mining process, deposited in decreasing sizes but still on a colossal scale. The land deposit of the finest tailings, an industrially produced type of sand with particle sizes less than 0.5 mm, grows by 2 million tonnes every year. The first landfill, initiated in the early 1990s, now covers an entire valley with a depth of up to 100 meters.5

The paradox of the invisible, immaterial pigment and its profound, irreversible impact on the local environment is central to my research and the reason why I find it particularly compelling to study titanium dioxide through ceramic processes. In ceramic glazes, titanium dioxide influences the development of color by chemically reacting with surrounding substances. Consequently, it is primarily used for its ability to create opacity and, in some cases, crystalline structures rather than white surfaces. During a glaze firing, titanium dioxide sheds its quality as a light-refractive technology and reveals itself as the material agent it truly is – a mineral particle of the earth element.

Fig. 4. The MoW group inside the old mine in Blåfjell. Photo: Marte Johnslien.

As part of my teaching in Ceramic Art over the past two years, MFA students of Medium- and Material-based Art6 have been involved in the research project TiO2: The Materiality of White (MoW)7. Teaching in the MoW group takes place on five levels: Introduction to the history of titanium dioxide, fieldwork at the mining areas in south-west Norway, collaboration on the technical compendium TiO2 in Ceramic Glaze, individual artistic work, and exhibitions.

Along with my assistant, artist Julia K. Persson, the MoW group has accompanied me to Titania’s mines and deposits, gathering local materials and information. Much like geologists who explored the Sokndal area over 150 years ago in search of valuable minerals, our group has traversed the landscape, collecting stones, sand, clay, and rust-colored earth. Through this process, we have gained insight into how the global industry of titanium white pigment is connected to the history and context of this specific geographical zone.

The first ilmenite mine was in a mountain called Blåfjell, named for its color, so dark it is almost blue. One can imagine the 19th-century geologists’ reaction when they picked up a stone from the ground. Consisting of a high iron level, the rocks are very heavy and leave dark, metallic dust on the hand.

Inside the mine, the mountain reveals its many colors to us in the last rays of light that touch the walls before we are swallowed by the darkness. We pick pebbles and pieces of ilmenite ore from the ground and carry them with us as we continue our journey into the mineral sites of Sokndal.

At Tellnes, the open-pit mine that has been Titania’s main production site since 1960, we head for the waste rock deposit. On the day of our visit, the wind is strong and cold, and the dry, white snow drifts around our hands as we reach for the multi-colored rocks that emerge as we search. We find quartz, feldspar, olivenite, and anorthosite in the waste rock. We knock them loose from their frozen earth beds and carry them with us to the next deposit: the historical sand deposit in Sandbekk, where Titania had its first large-scale production site from 1916 to 1965.

The underground mine Storgangen is closed to the public, but with the guidance of Stene and Hammonds, we are shown around the area. The mining industry has left behind millions of tonnes of fine tailings in the region. The sand was transported by cableway from the crushing facility to the top of the nearest mountain, where the carriages tipped the fine sand down the slopes. Today, a few fragile trees and mosses grow in the sand, but the landscape is forever transformed and deprived of its natural contours and vegetation by the 25-meter-deep sand deposits.

We bring the rocks, sand, and earthly findings back to the Oslo Academy of the Arts ceramic laboratory, where we further investigate them through ceramic processes. Additionally, we return with bodily experiences and first-hand knowledge of how the mining industry affects the nature and landscapes of Sokndal. This forms the foundation for the next part of the project: to transform the materials and embodied knowledge into artworks.

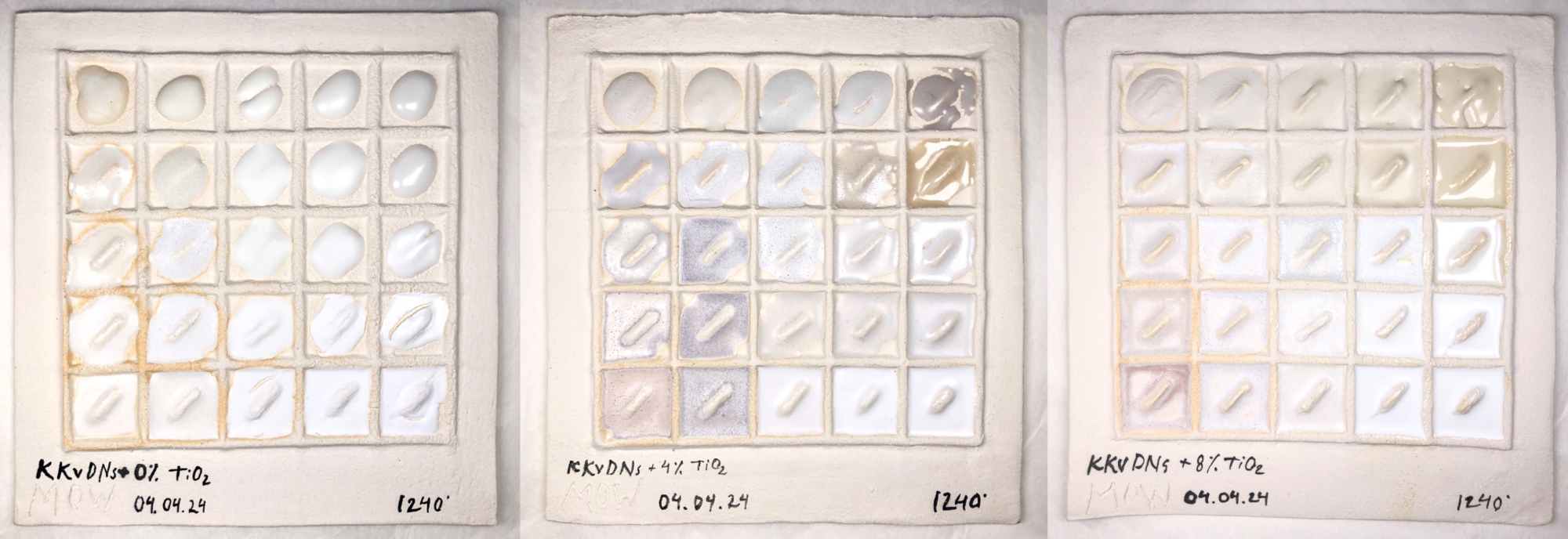

Collectively, we are also developing glaze recipes with titanium dioxide and a limited number of substances found in Norwegian geography: kaolin, quartz, nepheline syenite, chalk, wollastonite, and/or dolomite. Using a simplified version of the Ian Currie grid method8, developed by workshop master in ceramics Knut Natvik, we are working on creating glazes from titanium dioxide and the six substances, leading to the publication TiO2 in Ceramic Glaze, due in 2026. In group workshops and through ongoing research by assistant and artist Julia K. Persson and myself, we aim to create an open-access publication detailing our work methods, testing systems, and glaze recipes, along with the context. This work enhances our understanding of how titanium dioxide affects ceramic glazes, shifting our perception of it from a mere colorant to a physical property. Some of the functional glaze recipes we have developed have evolved from coded test tiles to have descriptive names, such as Titadon, Cream White, Silverspot, and Titanium Rivulet. By applying a set of limits and rules to the process, we maximize the learning process for the glaze students and become more conscientious of the glaze’s impact on nature and health, as each substance is traceable to Norwegian geology and not deriving from industrial composites.

The major goal for 2024, however, was the exhibition Hidden Stone at Velferden. In this exhibition, I aimed to showcase our group’s investigations into titanium dioxide (and related materials) in ceramic art, thereby highlighting the industry’s impact on nature, landscapes, and our surroundings.

In Western culture, white symbolizes purity, innocence, power, and progress. By processing the color white and related materials in ceramic sculpture, I encourage the students in the MoW group to critically examine this symbolism by tracing the color back to its mineral origins and geographical roots. Based on our study trips, conversations, texts, and the art and glaze work we have explored as a group over the past 1.5 years, the students were asked to create a ceramic artwork for the exhibition that relates to the act of bringing titanium dioxide back to its earthly origin. The story is broad and comprehensive, and the seven artists each have a unique perspective. In many of the works, the students used the titanium dioxide glazes we had developed in the workshops, as well as applying glazes produced from the harvested materials.

At the entrance to Velferden, you are greeted by Julia K. Persson’s work, White Canvases, made of textile forms filled with liquid clay, which will dry or become moist depending on the weather. The work explores how we see and experience the color white. The installation’s various shades of white mirror and reflect different colurs and lights from the surroundings. Textiles that individually appear white no longer seem white; some look green, some yellow, some blue, depending on the light and situation. This makes us aware of how sensitive our eyes are to nuances and that we perceive colors in relation to their surroundings.

In the stairwell and the banquet hall, you encounter Linda Flø’s ceramic reliefs. The reliefs are made by hammering waste stone from the mining industry in Sokndal onto soft clay. The texture becomes sharp and angular, somewhat like the terrain or topography of Sokndal. The reliefs are glazed with both titanium dioxide and sand from the deposit in Sandbekk – the product itself, and the waste left behind by the industry. The stones attached to the reliefs are titanium-rich iron ore from the old Blåfjell mine and waste stone from the deposit at Tellnes. The reliefs can be perceived as landscapes on both a micro and macro scale, creating dizzying images of the connections between the mining industry, nature, and human bodies down to the cellular level.

In Iliana Maria Papadimitriou’s work SPF 1240, one follows the metamorphosis of ilmenite from dark iron-rich ore to pure white pigment. The ceramic containers have been sprayed with local ilmenite and combined with waste sand and metal from Sandbekk. The containers house and highlight ilmenite’s ultimate form: titanium dioxide. They contain homemade sunscreen made by the artist, using titanium dioxide as the raw, active ingredient from the same lab MoW glazes were produced. Thus, titanium dioxide is presented as a key product of both the mining and cosmetic industries, respectively.

Fig. 9. Linda Flø, Terreng i farger, I. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Fig. 10. Linda Flø, Gjenforening I and Gjenforening II. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Fig. 11. Iliana Maria Papadimitriou, SPF 1240. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Sara Bauer Gjestland Zamecznik presents two sculptures that can both be touched. Carved Stone is a stone-like sculpture that can be opened. With this sculpture, the artist wants to explore the complete darkness one experiences when entering a cave and the total light that blinds when leaving it.

The large sculpture Krinkete krok can give the viewer a sense of not knowing if it was made in this century or discovered in an archaeological excavation. The form invites the public to explore not only with their eyes but also with their hands to experience its complexity. The sculpture Krinkete krok is glazed with a titanium dioxide-rich recipe, thus creating a bone-like surface fused to the clay body.

Quin Scholten presents two series of sculptures. In the mountain series, Scholten puts the mining industry in dialogue with the Norwegian troll. The sculptures show the mountains being “squeezed” and hollowed out by the industry. The trolls refer to the cultural and mythological history of the landscape, playing on the trolls’ role as protectors of the landscape.

Pitcher is a series of three ceramic sculptures glazed with Titanium Rivulet standing on bases with ilmenite-rich glazes. The footings have also been textured with ilmenite stone, making the stone both literally and metaphorically a support for the titanium oxide pitcher. Ilmenite gathered from Blåfjell and industrially produced titanium dioxide are the main elements in the glaze and design of Scholten’s ceramic works. He delves into cultural history and the Norwegian folk soul to bring forth new images of everyday objects, folklore, and the mountains’ impact on life in Sokndal.

Another artist drawing from Norwegian cultural history is Silje Kjørholt with the work Utilstrekkelig overalt del 1. The sculpture consists of a red-painted surface (like a traditional Norwegian barn wall), marine blue clay mixed with straw, and titanium white paint. In this work, Kjørholt dwells on the contrast between ilmenite in the hard rock and the white powder made from it. An even greater contrast is between the white powder and the earth; these contrasting qualities could represent the oppositions of purity and impurity. When you scratch the surface, a shared origin is revealed, with intersecting or overlapping qualities.

Fig. 13. Sara Bauer Gjestland Zamecznik, Carved Stone. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Fig. 14. Sara Bauer Gjestland Zamecznik, Krinkete krok. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Fig. 15. Quin Scholten, Being Poured Over. Photo: TiO2 Project.

Fig. 16. Quin Scholten, (Bending) Pitcher and (Quad) Pitcher. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Fig. 17. Silje Kjørholt, Utilstrekkelig overalt del 1. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

We display glaze tests and material samples on the wooden structure in Hidden Stone, which was named the “control panel” of the exhibition. Here, Linda Flø demonstrates how she has developed glazes based on Blåfjell ore, sand from the deposits, and blue clay she gathered in Sokndal. We also present the titanium dioxide grids, where one can see how a consistent amount of titanium dioxide in each little square reacts with varying amounts of silica, alumina, and melting agents to form an endless number of textures, glosses, and color variations. The grids display the complexity of titanium white and its material context, making it both hard to grasp and optically confusing.

In a conversation the day before the opening, I prompted the students to reflect on what the exhibition had meant to them. It was clear that each person had approached the context of the color white from their own perspective, yet using the same materials gave the exhibition a visual coherence, particularly in terms of its color scheme. Iliana Maria Papadimitriou noted that the exhibition possessed a certain rawness because the materials were approached with honesty, highlighting their qualities as well as their role and value. Linda Flø added that the process of collecting the materials and learning about their history and context nurtured a deeper appreciation and care for them.

The physical effort involved in gathering these materials, set against the backdrop of the post-industrial landscape juxtaposed with the area’s natural beauty, imbued even the waste rocks and sand tailings with emotional value, she elaborates. This heightened sensitivity and economical use of the substances in the workshops surpassed what could be achieved with industrially produced ceramic glaze ingredients in a lab setting. The act of personally collecting the rocks, ground ilmenite from Blåfjell, and the scattered sand from the landscape enhanced the emotional value of these materials, which, despite being classified as waste, were infused with new significance through our labor and translated into the artworks.

Fig. 19. MoW, test tiles and grids. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Quin Scholten adds that the process also involves “world-building”. By delving deep into the context of materials and retelling their stories from our individual perspectives, we create new contexts for these materials. The artworks in the exhibition are centered around narratives of landscapes, the intrinsic value of rocks, and mythologies of nature, diverging from the human-centric narratives that typically dominate the history of the mining industry.

When asked about the distinctive aspects of this exhibition compared to others in ceramics, Sara Bauer Gjestland Zamecznik highlights the site-sensitive nature of the artworks. She notes that observations from our field trips have unexpectedly emerged in the sculptural works: from the old iron cableways (now buried in the sand) and stark light rays in the old mine to individual angled surfaces of collected ilmenite rocks. Thus, we have not only processed the physical materials but also distilled our experiences of them into the artworks themselves.

The students’ reflections resonate with my own thinking. Everyone presented works with a defined personal artistic expression, which nonetheless spoke in the same “tongue” – that of the site-specific origin of the artworks, which were reflected in color, texture, and reference to the local industry. We may have acted as artists who travel, select, crush, and consume natural materials, not unlike the industry itself, only on a micro-scale. However, our work was additionally an investigation into the value of waste rocks, sand tailings, and the post-industrial landscape, which I believe could give the local audience a new perspective on the mining history of Sokndal when visiting the exhibition Hidden Stone.

The most significant finding in the process, however, was how we, as a group, developed a collective emotional tie to the landscape and the history of the local area. To harvest materials, an activity that has momentum in contemporary ceramics, is not only about developing a more sustainable approach to making ceramics. It is a practice of creating connections. By acquiring knowledge about natural resources and the mining industry’s impact on the local landscape, bonds are grown to that place and context.

One may look at the containers of chemical substances in the glaze lab and imagine the mining, pollution, and loss of landscape that lies behind the content of each one of them, which can dishearten any one of us. However, as artists, we are in a unique position to process facts and numbers and create new experiences and perspectives from them. We may enter the industrialized landscape, gather and investigate the minerals, and tell the stories about the material’s circulation in the modern world in new ways. We cannot slow down the global pigment industry, but we can create artworks that make us see new sides of our shared material reality and perhaps catch some glimpses of visions for a different future.

Marte Johnslien (b. 1977) is a visual artist and researcher who lives and works in Oslo, Norway. She is an Associate Professor in Ceramic Art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, Department of Art and Craft, and holds a PhD in artistic research. She is the PI of the research project TiO2: The Materiality of White (MoW) and Co-PI of TiO2: How Norway Made the World Whiter (NorWhite), in collaboration with art and architecture historian Ingrid Halland (UiB).

Process, perception and materiality are keywords in her practice. Her projects are often anchored in historical research and material investigations. The project White to Earth (2020) investigated the materiality of titanium dioxide and how the white pigment travels through our systems seemingly invisibly. The work consisted of two series of ceramic sculptures and a photo-illustrated book. The project formed the basis for the current collaborative research projects TiO2: MoW/NorWhite. The projects aim to write a critical history of white pigment based on archive studies, material investigations, and interdisciplinary collaborations.

Marte Johnslien’s work has been included in exhibitions at the Norwegian National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, The Astrup Fearnley Museum of Art, Norway, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp, and the 12th Havana Biennial in Cuba. She has held solo exhibitions in the Lillehammer Art Museum, Henie Onstad Art Center, Galleri Riis, and Kristiansand Kunsthall, Norway. She is the recipient of the Einar Granum Art Award (2012). Her work is included in the collections of the Norwegian National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Henie Onstad Art Center, Sørlandet Art Museum and Lillehammer Art Museum.

Marte Johnslien is represented by Galleri Riis, Norway.

Ceramics Now is a reader-supported publication, and memberships enable us to publish high-quality content like this article. Become a member today and help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Featured image

- Julia K. Persson, White Canvases. Photo: Hans Edward Hammonds.

Footnotes

- TiO2: The Materiality of White collaborates with the research project TiO2: How Norway Made the World Whiter at the University of Bergen, Norway, led by Associate Professor in Art History Ingrid Halland. For more information about the collaborative research work, please visit the project’s website.

- The inconspicuousness of titanium white is further discussed in Ingrid Halland and Marte Johnslien’s article “‘With-On’ White: Inconspicuous Modernity with and on Aesthetic Surfaces, 1910–1950,” Aggregate 11 (January 2023), Link.

- Marte Johnslien, “White to Earth”, 2020. An artist’s book and the final result in Johnslien’s PhD in Artistic Research marks the beginning of the TiO2 Project. https://khioda.khio.no/khio-xmlui/handle/11250/2655680

- Titania AS and Kronos Titan AS have since 1927 been under the ownership of the American multinational company Kronos Wordwide.

- Are Korneliussen, Suzanne A. McEnroe, Lars Petter Nilsson, Henrik Schiellerup, Håvard Gautned, Gurli B. Meyer, Leif Roger Størseth. ‘An overview of titanium deposits in Norway’. NGU-Bulletin 436-2000 (2000).

- The MoW group consists of MFA students in Medium- and Material-based Art in the subject area of Ceramics at the Art and Craft department at Oslo National Academy of Arts.

- Supported by the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme.

- Link