By Aleina Edwards

As a multimedia artist predominantly focused on ceramics, Simone Leigh is very concerned with her material—its essence and associations, its myriad histories. In the past two decades, Leigh has made a name for herself by rendering figures in clay, using racially-charged images like face jugs, cowrie shells, and stylized busts to reclaim and reconstitute the Black femme form. Now, as her first museum survey show settled into its final stop in Los Angeles, Leigh’s visual vocabulary has become a vibrant language, her sculptures nearly mythic.

Simone Leigh has its roots in Sovereignty, the artist’s presentation at the 2022 Venice Biennale—the United States’ first by a Black woman. Nine of the pieces from the Sovereignty show have migrated to Simone Leigh, which is currently split between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the California African American Museum. Of the 29 pieces on display across both locations, nearly all are based in clay. The sculptures range from small stoneware busts to large-scale figures clay-modeled and cast in bronze. Everything, from the 9-foot-tall Sharifa (2022) to each rosette in a figure’s hair—is first molded by hand. In Leigh’s worlds, people come from clay; the cowrie shell and the jug vessel are sacred symbols; women’s work and African vernacular architecture are elevated; and bronze bodies become beacons of belonging.

Leigh’s forms have grown over the years, and monumental figures mark the entrance to each half of the show, signaling new spaces with new rules. At LACMA, 16-foot-tall Sentinel (2022) stands outside the Resnick Pavilion; at CAAM, Cupboard (2022) glistens gold near the front doors, even at night. Sentinel references the West African “power object”—a ritual vessel or figure that contains and releases divine energy—and the effect here is both elegant and mystifying. The figure’s head is a circular dish akin to a satellite; we don’t know what it’s sending, or receiving. Outside CAAM, Cupboard also complicates the idea of welcome and the roles that Black women are expected to play in domestic spaces. In a resplendent and ominous recharacterization of the mammy archetype, Cupboard offers us her arms, but they are cut off above the elbows. She faces us, but she has no eyes.

The gaze is a mechanism of power and a means of control, especially in portraiture, and most of the pieces in Simone Leigh are portraits of Black femmes that vibrate in the tension between object and subject. In the first room of the LACMA presentation, there are three new bronze sculptures: Herm, Vessel, and Bisi, each made in 2023. There are traces of the artist’s hand visible on the forms, little indentations where fingers pressed against clay models. With their sensuous forms and elegant finishes, they are alluring, but self-contained. As with all of Leigh’s figurative sculptures, their faces are impassible—they’re eyeless, actually. Their eyelessness represents generations of invisibility and subservience, but it also serves as a shielding mechanism; eyes are emotional access points, and Leigh doesn’t give them readily. Her figures are relatively inscrutable to the museum-goers milling around them—and in them, in Bisi’s case. Standing under the bell of Bisi’s hoop skirt, I get the sense I might be intruding, not sheltering. She, like the Cupboard figure at CAAM, has no arms. Nearby, Herm sticks one foot out of her rectangular column of a body, maybe trying to escape the confines of her body, or interrupt the walkway. I am not entirely sure what is happening, or where I belong—it’s uncomfortable, and that’s the point. Through such subtle and specific formal choices, Leigh generates a kind of helix: an ongoing, interlaced discourse about racial and gendered hierarchies and norms.

Leigh’s authoritative figures hold space for Black women first and foremost, their scales, shapes, and placements transforming the museum space into sacred halls. The pieces in the LACMA installation have plenty of room to themselves, and the Resnick Gallery—even on a free admission, family-friendly evening complete with drinks and a DJ—has the relatively hushed reverence of a church. Positioned in the middle of walkways and watching from perimeters, the looming figures and busts on tall pedestals require acknowledgment and invite admiration, but refuse to engage stares. All but four of the pieces at LACMA were made post-Biennale, and there isn’t an obvious progression across the galleries; it’s as though this is what Leigh has always been making. Many of the individual elements—hoop skirts and tight rosettes, refined symmetries and smooth faces—are familiar now. These are people that we are beginning to recognize and interact with on their own terms.

Leigh, as always, finds her force in a fusion of theory and materials. Ceramics, porcelain, and terra cotta have traditionally been considered craft materials, the foundations of functional objects—women’s fare. Bronze, however, is masculine, revered, and timeless. The intersection of these materials and practices—one rooted in craft, the other in fine art and architecture—is emblematic of Leigh’s hybridization, or what Leigh’s friend and historian Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation”—a type of reparative, generative storytelling that collapses time and place to articulate both a truer history, and a more beautiful future. Darkly revelatory and magically aspirational, these kinds of stories encompass the best and worst of humanity. They are, in short, sublime.

The terrible beauty Leigh has conjured in the past twenty years is undeniable. At CAAM, it’s visible in the bell curves of Cupboard’s cascading raffia skirt, and the green glisten of Breeze Box’s (2022) glaze. It’s visible in the oldest piece in the entire show, White Teeth (for Oto Benga) (2004). Clustered rows of porcelain teeth in various, muted hues line a metal, mirrored box. They stick out at all angles, almost crystalline. Several friends and I stand on either end of the box, looking in at this kaleidoscope of fantastical teeth. It’s only after I Google the piece that I learn about its namesake, an enslaved Black man whose teeth were sharpened to points against his will. All of Leigh’s works are like this: rich and multifaceted, working on multiple aesthetic and theoretical levels.

By rendering her subjects with such scale and dignity—such striking beauty—Leigh creates a world where their histories are validated, and their futures are promised.

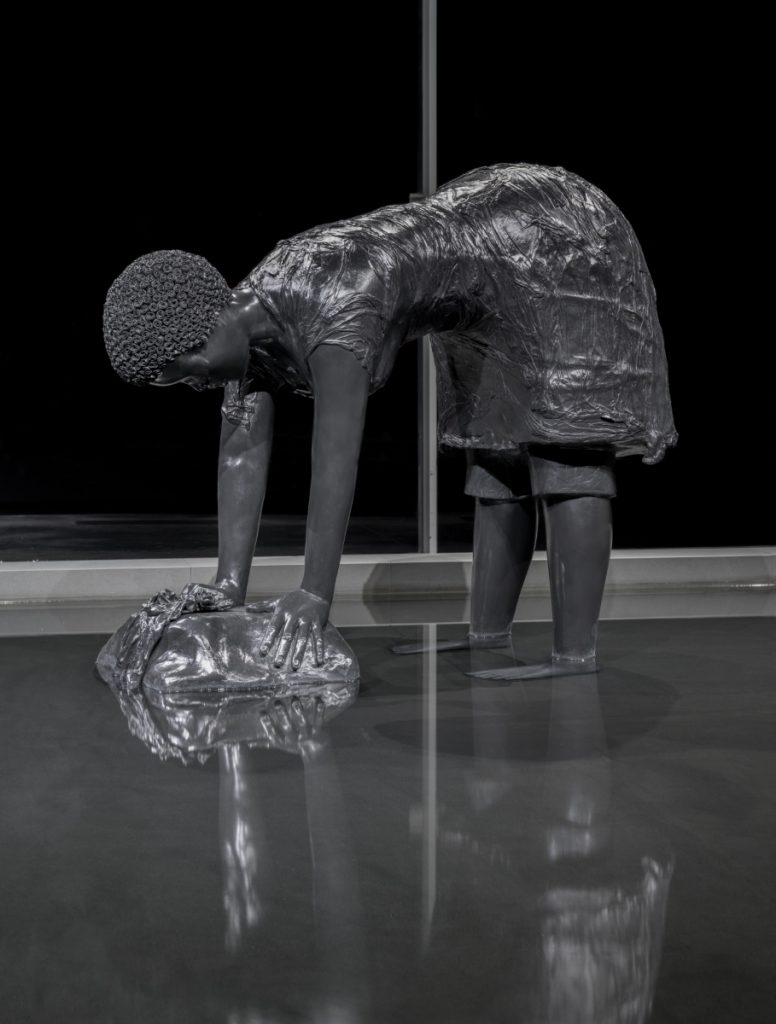

But just as beauty is intertwined with subjugation in Simone Leigh, it also becomes an antidote to violence—it casts a protective spell. This effect is evident in Leigh’s newer works at LACMA. Untitled (After June Jordan)—a 16-foot-tall tower made of 988 ceramic cowrie shells, all hand-shaped and uniquely glazed—stretches to the ceiling. A pair of shimmering sphinxes lounge on the floor, a little enticing and a little threatening. Just beyond them, a dark figure bends over in a reflecting pool, as if rinsing something in the water. This is The Last Garment (2022), based on a popular 19th-century postcard from Leigh’s parents’ native Jamaica.

In a 2022 interview for the New Yorker, Leigh described one of the themes of her Biennale show, the souvenir—”the idea that we like to bring other worlds into our world.” The souvenir, she explains, “is a seemingly harmless object that has actually proven to be quite devastating.” She refers specifically to the image of the washwoman in Jamaica, a representation of Black subservience and labor that circulated the world, and the inspiration for The Last Garment. Souvenirs—a postcard to fit in a pocket or a mug to stuff in a carry-on suitcase—are trivialized as trinkets, but can be emblematic of entire cultures that have been extracted and abstracted. To take something as a souvenir is to destroy its context, to fundamentally change its story.

So Simone Leigh presents a new story. The Last Garment was modeled on the figure of Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, a scholar and friend of Leigh’s. Leigh created the sculpture, twice the size of its referent, in clay before casting it in bronze—she also hand-sculpted each of the 800-some rosaries that make up the figure’s hair. By transforming a four-by-six image into a carefully crafted monument fashioned after a close friend, Leigh both highlights racist, extractive dynamics and reasserts the value of the people they affect. By rendering her subjects with such scale and dignity—such striking beauty—Leigh creates a world where their histories are validated, and their futures are promised. Outside LACMA, the setting sun paints the sky pink.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Aleina Grace Edwards is the Director of Craig Krull Gallery in Santa Monica, and she writes about contemporary art in California and the American Southwest. Find more of her work at aleinagraceedwards.com.

Simone Leigh, a traveling exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA) and co-presented in Los Angeles by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the California African American Museum (CAAM), is the first comprehensive survey of the richly layered work of this celebrated artist. The shows are on view through January 20, 2025.

Ceramics Now is a reader-supported publication, and memberships enable us to publish high-quality content like this article. Become a member today and help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Captions

- Simone Leigh (exhibition view). California African American Museum and Los Angeles County of Museum of Art, May 26, 2024 – January 20, 2025. Photos by Elon Schoenholz

Comments 1