By Doug Navarra

From the outset, I found Mai-Thu Perret’s work in the exhibition titled “Underworld” at the David Kordansky Gallery in NYC to be deeply challenging, which immediately drew me to it. This challenge arises from multiple factors: the work is interdisciplinary and conceptual, departing from traditional notions of ceramics while also offering a fluidity of meaning that invites viewers to actively participate in shaping their artistic experience. If we consider content to be the catalyst that elevates the viewer beyond mere engagement with an artwork and into a deeper realm of contemplation, then this exhibition enriches that dialogue by presenting it as a dynamic and multifaceted experience.

Mai-Thu is renowned for her ability to create works that intricately weave contemporary cultural dialogues with art historical frameworks using a who, what, where, when and why, broad definition of what materiality really is within contemporary and historical lexicons. Yet within that, she consistently emphasizes the tangible qualities of her materials, revealing how the physical properties of these materials contribute to the artwork’s meaning and impact. The depth of her statements highlights the interconnectedness of culture, a broad comprehensive understanding of materiality, as well as the transformative nature of her work.

In the center of the exhibition space there exists a large tomb-like structure guarded on the outside entrance by Siren I and Siren II, free-standing sculptures. The Siren figures are inspired by the sculptural grouping “Orpheus and the Sirens,” a Greek work from 350-300 BC that was originally part of the Getty collection and has now been repatriated to Italy.1 Drawing inspiration from these two ancient sentinels of the underworld, this work reinterprets anatomically scaled figures that similarly evoke mannequin-like features. They showcase clay that has been modeled to accurately reflect the proportions of the upper human torso, seamlessly combined with bronze castings of oversized bird-like legs. In their striking visual departure, these assemblages skillfully blend two very different materials, glazed ceramics and bronze casting, while resulting in unsettling and disquieting images that possess an enduring yet timeless presence.

Creating hybrid forms by blending ceramics and bronze involves a fascinating interplay of techniques and materials. This fusion not only creates visually striking works but also explores the contrast between the fragility of ceramics and the durability of bronze. Ceramics, often perceived as delicate and prone to breakage, embody vulnerability and impermanence. In contrast, bronze is renowned for its strength and longevity, often symbolizing resilience. While, in this case, the fragility of ceramics can symbolize the transient nature of life, bronze might represent strength, a décor of permanence, and, in fact, the weight of history. This duality of materials reflects a visual tension because each material actually carries with it a cultural history of its very own. In a sense, the combination of the two is where she weaves her conceptual narrative of both past and present.

Leading into the central tomb-like structure, we find another ceramic figural work, titled Build fire and read the future in smoke, presenting an organization of body parts either waiting for assembly or detached from one another. But astonishingly, the torso exhibits signs of pregnancy! This was unsettling for me because, at first, I saw the hopeful potential of life in the piece. However, afterward, that initial sense of hope became overshadowed by a turbulent and unsettling portrayal of despair stemming from the separation of its parts.

In the inherent duality within this piece, we then witness the emergence of life alongside its departure, in a sense forcing a confrontation with the intrinsic uncertainties of life. This invites a dialogue which values emotional and intellectual engagement over purely formalist concerns. This intentional and continued emphasis on the conceptual foreground shifts the focus from the purely aesthetic qualities traditionally associated with ceramics towards the deeper meanings within the works, a consistency that runs throughout the entire exhibition.

Her orientation appears to encourage viewers to dive deeper into their own thoughts and experiences. I’m not sure if it’s just me, but I often sense a feeling of fear and unease whenever I encounter models of detached body parts within the art mainstream. In my mind, this ushers in a reflection of the Jamal Khashoggi event, who was assassinated at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018. It’s worth noting that anatomical elements have also been vividly represented in recent art, as demonstrated by Bruce Nauman, Kelly Akashi, Amy Pleasant, and ceramic artist Clementine Keith-Roach, all of whom incorporate disembodied features into their work

While the fragmented body parts may initially appear unsettling, they invite interpretation and emotional connection. In this way, Mai-Thu encourages viewers to reflect on their own feelings and perceptions. By depicting body parts separately, she is symbolizing the human condition, illustrating how some individuals may experience a disconnection in society. I also think this fragmentation emphasizes the existential nature of a somewhat fraught reality.

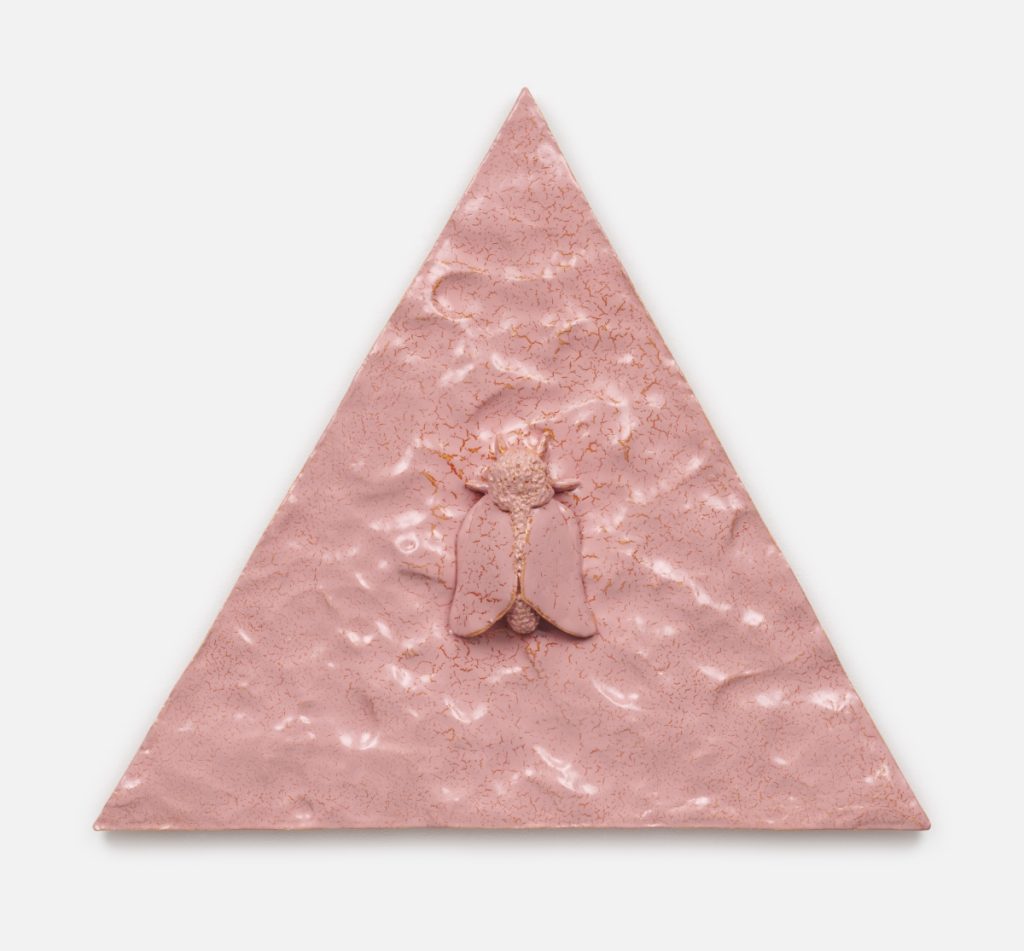

I would be remiss not to mention the nine-piece, massive triangular wallwork titled Underworld, a tour de force and the namesake of the exhibition. If you work with clay, it’s difficult not to appreciate the boundless gestural qualities of this piece and the way she manipulates the material as a visceral visual component. The title “Underworld” suggests a journey into the depths, both literally and metaphorically. It evokes a theme of the unknown, particularly the hidden realms of the unconscious. The chunky geometric shapes in the top triangular section of the work seem to transform into bird-like motifs in the lower triangular quadrants. This visible transition invites the viewer to ponder deeper existential questions of change while, at the same time, it evokes an underworld of myth as a place of both danger and potential rebirth.

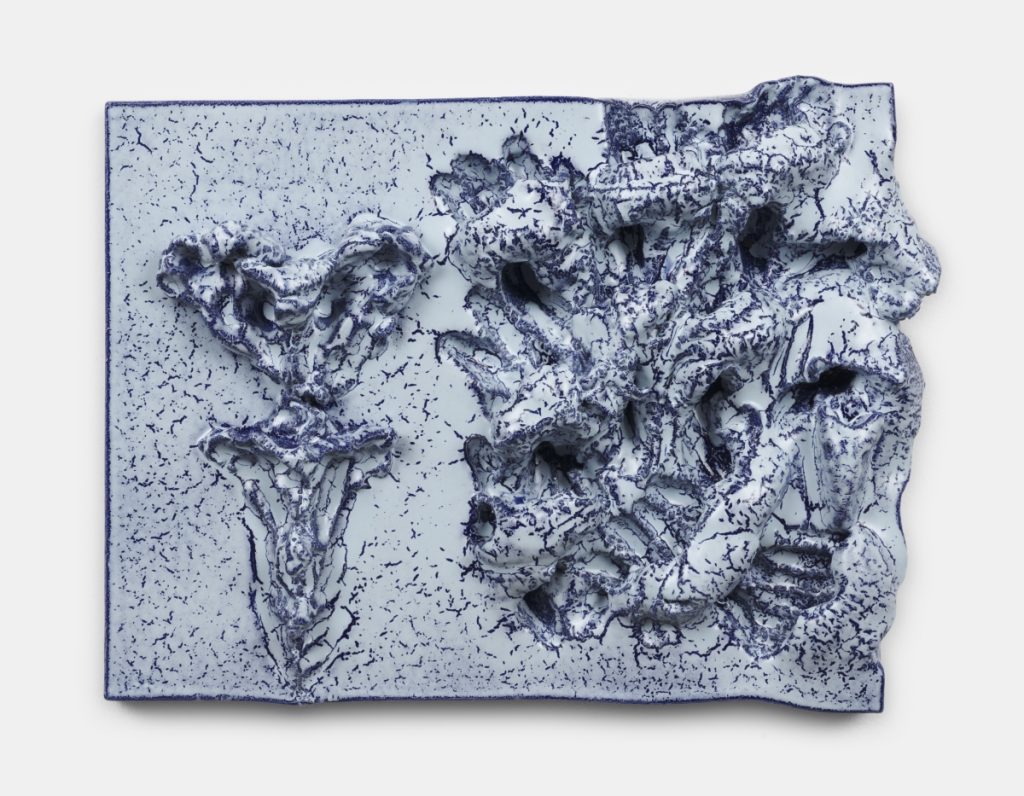

I gravitated to the smaller rectilinear wall-mounted works where the titles are poetic, and although smaller in stature, they are amicably grandiose, where meaning is ascribed if not reinforced in the material itself. Here is where I fantasized about which one I would like to own! As in the piece titled The song ends, no one in sight; over the river, several peaks are blue, it possesses this visceral visual component that elevates the statement by underscoring the profound sensory engagement that the artwork elicits. It implies that the visceral manipulation of clay has a wonderful raw and “open” quality to it. This is another example that goes beyond mere aesthetics. It invites viewers to connect with the work, I’d say, on an instinctual and almost intensely emotional level. It also implies that visual stimulus alone has the potential to be a formative means of achieving a deep penetrating form of content that moves the viewer into an advanced state of thought. You may lose yourself in this piece by connecting to it as an immersive personal experience.

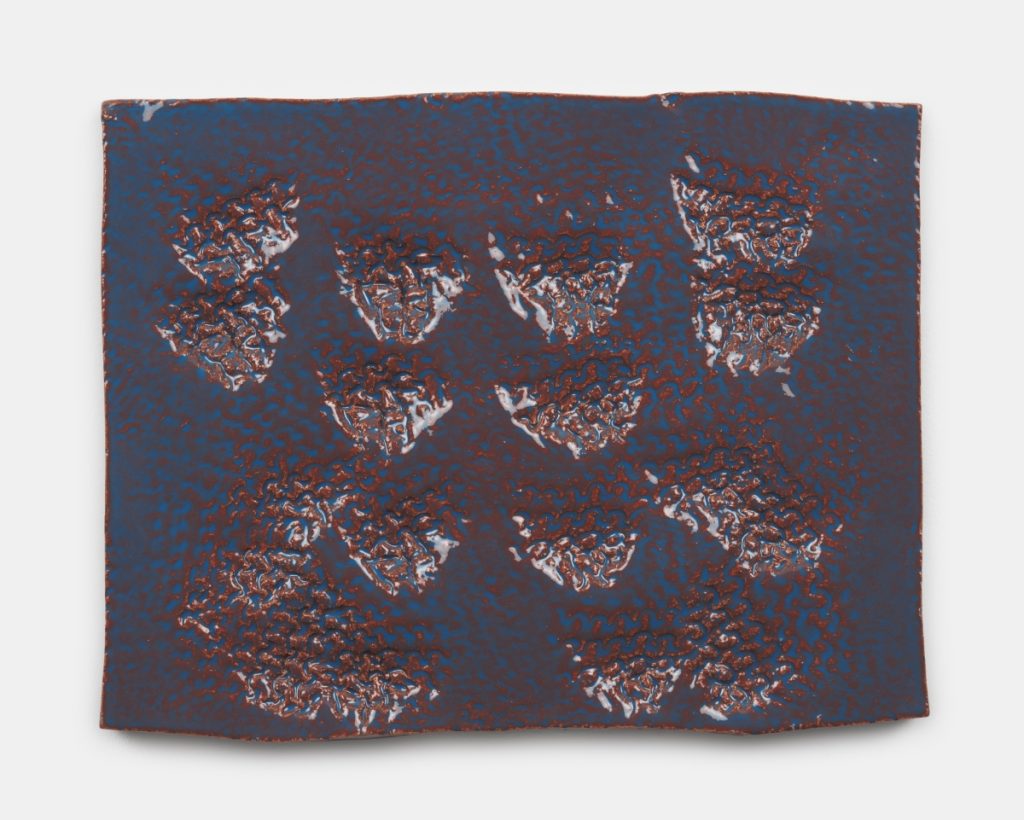

A similar tension is evident in the other wall-mounted ceramic works on display. Consistent conceptual foregrounding emphasizes relationality, focusing on the connections it creates—both between the viewer and the artwork and between the artist and her creation. What I find most compelling about these works is their focus on the dialogue that unfolds in the liminal space between the object and the viewer. This interaction suggests that meaning arises from the engagement itself rather than being confined to a fixed identity of what is seen. Each encounter with a piece leads to different interpretations and emotional responses, influenced by both the viewer and the work’s representational or non-representational elements.

These works are not merely objects to be observed; they serve as catalysts for interpretation. They reinforce the idea that meaning in these works is not static but transformative. By focusing on that liminal space between the viewer and the object, the viewer transforms from a passive spectator into an active participant. This essentially creates an open network, enabling viewers to shape meaning through their own subjective experiences. As a result, traditional notions of the artist as “author” are challenged. Of course, there is also an utterly magnificent representation of glaze technology at play as well.2 These works visually capture your attention, but they also resonate with your personal experiences and emotions.

Nowhere is it more apparent in these smaller wall-mounted works that Mai Thu entertains an attraction with vernacular ceramics, the everyday mass-produced ceramic items such as plates, dishes, and bathroom fixtures designed for functional, utilitarian use. Perhaps what initially strikes me is the limited production within the series of thick, rectilinear base forms, which begin with smooth, straight lines before she introduces powerful gestural manipulations, sometimes alongside recognizable objects. Her attraction to vernacular ceramics as objects of “everyday life” is key to her practice, as it allows her to contextually explore multiple dimensions.3

I have long advocated for examining contemporary ceramics through an anthropological lens, especially when the works carry an inherent cultural specificity, as is the case here. In a sense, these works are turning the vernacular on its head by recontextualizing forms typically associated with domesticity (such as commercial bowls, jugs, plates, etc.), subverting the functional role of ceramics into sculptures that address broader socio-cultural concerns. This carries historical practice and cultural concerns from ceramic communities where “women’s work” has historically been relegated to crafting traditions. The anthropological roles of gender, craft, and cultural history are quite distinctive here. It reforms the traditionally gendered division of craft by challenging the marginalization of feminine labor formerly relegated to domestic or small-production cottage industries. This is her blending of tradition with modernity, blurring the boundaries of the domestic with the artistic, which forms the core of her relationship with the vernacular. This almost intrinsic connection to the vernacular provides a nuanced approach to engage in an anthropological investigation, allowing her to explore the cultural specificity of being a female fine artist in the mainstream today.

In conclusion, Mai-Thu Perret’s “Underworld” exhibition offers us a broad exploration of materiality, cultural history, and the complexities of her own identity through the lens of contemporary ceramics. Her works also challenge traditional perceptions of both the medium and its meaning. “Underworld” is an exhibition not just of objects but of points of reflection on gender, societal roles, and the human condition. By combining ceramics with bronze, she creates a conversation between fragility and strength, past and present, that highlights historical meaning. Her attraction to vernacular ceramics, typically associated with domesticity, subverts their formerly functional and utilitarian roles and transforms her own works as vehicles for broader socio-cultural inquiry, particularly around the role of women in art and craft. This exhibition encourages us to look beyond the surface and engage more personally with the material, its context, and the artist’s exploration of her own place in the world. Ultimately, Perret demonstrates how contemporary ceramics can transcend traditional boundaries, opening space for deeper reflection and conversation.

Doug Navarra is a visual artist who has an extensive background in working with clay. He lives in Hudson Valley, New York.

Mai-Thu Perret: Underworld is on view between October 25 and December 21, 2024, at David Kordansky Gallery, New York.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Captions

- Mai-Thu Perret, Siren I, 2024, glazed ceramic and bronze, 70 1/8 x 17 3/4 x 15 inches (178.1 x 45.1 x 38.1 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Siren II, 2024, glazed ceramic and bronze, 68 1/2 x 18 x 15 1/2 inches (174 x 45.7 x 39.4 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Build fire and read the future in smoke, 2024, glazed ceramic, dimensions variable. Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Underworld, 2024, glazed ceramic, 102 x 123 x 6 inches (259.1 x 312.4 x 15.2 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, The song ends, no one in sight; over the river, several peaks are blue, 2024, glazed ceramic, 15 1/2 x 20 1/2 x 3 3/8 inches (39.4 x 52.1 x 8.6 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Chaos has no seams, 2024, glazed ceramic, 15 1/8 x 19 1/2 x 2 inches (38.4 x 49.5 x 5.1 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Do not talk of what goes on in the women’s quarters, 2024, glazed ceramic, 34 1/2 x 39 x 3 1/2 inches (87.6 x 99.1 x 8.9 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

- Mai-Thu Perret, Erase footprints, wipe out traces, 2024, glazed ceramic, 33 1/4 x 38 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches (84.5 x 97.2 x 11.1 cm). Photo: Mareike Tocha, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

Footnotes

- Link

- I would like to give credit where credit is due, and that would be with the technical collaborative experience of the Niels Deitrich ceramic atelier in Cologne, Germany, where many of these works were realized.

- Published interview with Alexander Glover 02/02/2017 A. Glover: “You use ceramics frequently.” Mai Thu Perret: “Yes, I do; I think it’s because it’s such a fluid, tactile, and amorphous material. I also really like that it’s a material that you have in your everyday life. It’s in your bathroom or makes up your dinner plate. I really like that. It has a domestic feel to it.”