By Kristina Rutar

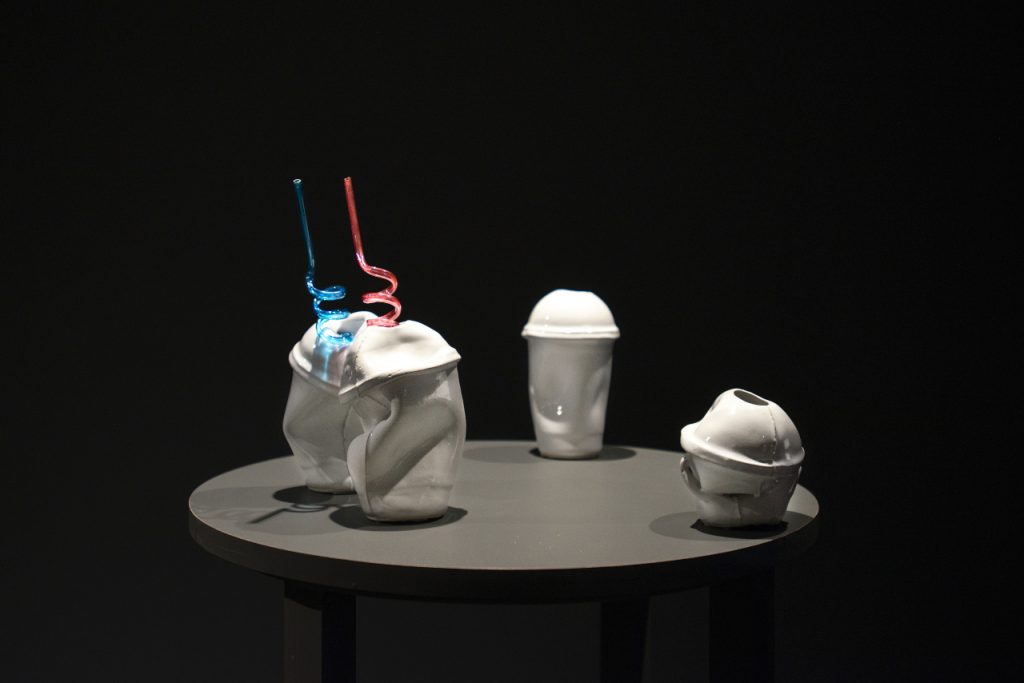

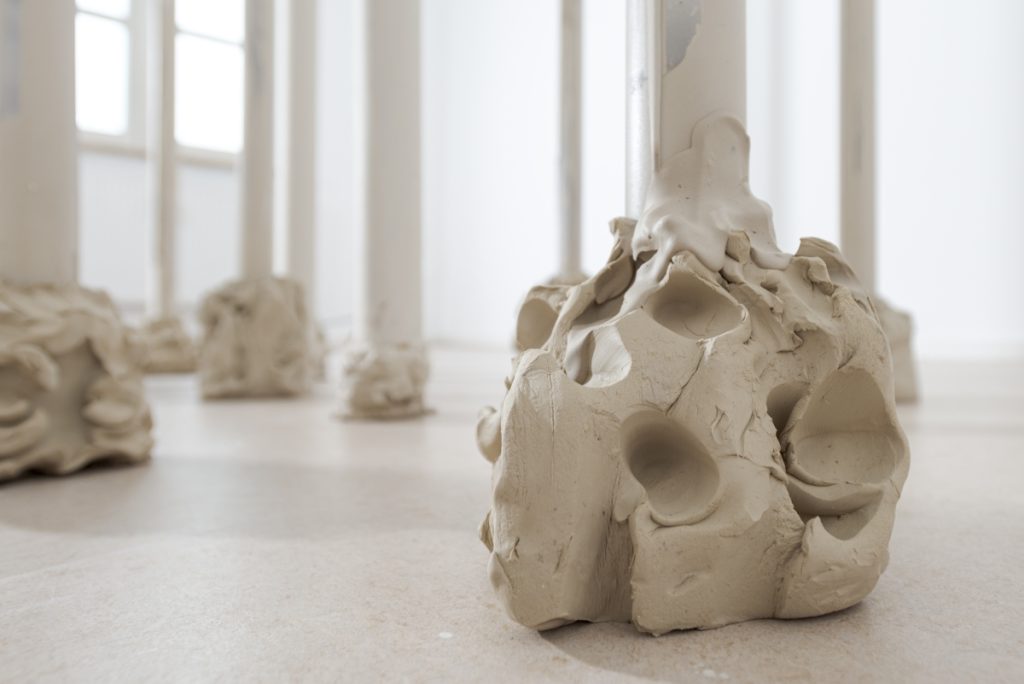

I first met Danijela Pivašević-Tenner in 2016 during my Tandem residency in Neumünster, Germany. As I was taking my first steps as a ceramicist, Danijela immediately challenged my understanding of the material. Her work made a lasting impression on me: installations transforming into paintings—the drying slip covering various utilitarian objects would begin to develop mould, creating new life and continuing its course on its own. Could a material have its own life without our interference? Could unfired clay even be considered ceramics? Why was sustainability so important to her? Why were most of her works unfired, and what was her understanding of the materials she used? And finally—why were these questions so important?

Last year, I had the opportunity to visit Danijela at the Universität der Künste in Berlin. Observing her approach to teaching and her philosophy of understanding her primary material opened new perspectives, which I’m eager to share with Ceramics Now readers. I hope you’ll find this interview as engaging as I enjoyed discovering new ideas through my conversation with Danijela Pivašević-Tenner.

Danijela, your academic background is grounded in traditional ceramics—you completed your diploma at the Department of Applied Arts, Ceramics, at the University of Arts in Belgrade. There, you received a comprehensive education covering all aspects of ceramics, including the technical details essential to the craft. Afterwards, you pursued a master’s degree at the Weißensee Academy of Art in Berlin.

Your work leans towards conceptual art, which might challenge the traditional understanding of ceramics. For instance, some might not recognize your work as ceramics because it often doesn’t follow conventional processes such as firing. I’m curious: given your traditional training, how and when did your perspective on ceramics shift to a more conceptual approach? When did you start developing conceptual ideas?

I studied in Belgrade during a turbulent time marked by wars, inflation, and political turmoil. At the beginning of my studies, Yugoslavia was still intact, but as the former republics gained independence, and later when Serbia briefly united with Montenegro, the idea of a stable country repeatedly dissolved. This constant change shaped my understanding of structure and permanence, leaving me with the impression that everything could be redefined.

My diploma studies lasted five years—an intensive and comprehensive programme quite different from contemporary BA and MA structures. While my focus was on Free Ceramics, the curriculum covered a wide range of subjects, including art history, anatomy, technical drawing, ceramic techniques, painting, drawing, glaze formulation, and product design. This broad education provided me with a solid foundation in the arts and equipped me to pursue various creative directions. Although my passion lay in ceramics, I quickly learned that an in-depth understanding of art history and related fields was essential for artistic development. Initially, I didn’t fully appreciate subjects like product design, but they ultimately contributed to my artistic growth.

Upon completing my studies, I decided to study abroad—not because I needed additional training (my education in Belgrade was quite comprehensive), but due to the region’s unstable political and social situation. The upheaval, wars, and general instability prompted me to seek a more secure environment for my practice. This brought me to Berlin, where I completed a Master of Arts and Art Therapy. Immersed in a new cultural setting with access to well-equipped workshops, and with the opportunity to work as a tutor, I was able to refine my skills. My shift from traditional to conceptual art stemmed from an internal drive, something that I had always felt but couldn’t fully define.

Do you think your art, after all your studies, would be different if you moved back to Serbia?

Absolutely. Although I’ve lived in Germany for 20 years and travelled extensively, I frequently return to Serbia to keep that connection alive. I participate in residencies and symposiums there, and I’ve noticed that when I’m in Serbia, my work becomes more socially engaged. This is a direct reaction to the local political and social climate. In Germany, there’s a stable social foundation that allows me to freely develop my thoughts and interests without having to worry about survival or basic rights. Here, I can engage in a more conceptual approach to art. Had I remained in Serbia, my work might have evolved more towards socially engaged art.

Sustainability is a key theme in your work and teaching. Has this always been the case, or did it develop over time? How do you incorporate sustainability into your teaching?

Sustainability has been central to my practice from early on. As a student, I was always eager to fire my pieces, and I understand how important that experience is for students. However, firing isn’t always necessary; understanding materials and techniques is more important. Firing may sometimes limit one’s creativity; it can be like focusing on a single tree while missing the forest.

My commitment to sustainability deepened after traveling through southern Germany and witnessing the environmental damage caused by the extraction of ceramic materials. This prompted me to research the origins of these materials and question the environmental cost of firing. I started limiting my use of materials, reusing and reclaiming them to create new works without contributing to unnecessary destruction. This approach allows me to create while remaining at peace, knowing I’m minimizing harm.

Sustainability in art is not just a trend—it’s essential. During my time running the Keramikkünstlerhaus Neumünster in northern Germany and in my teaching, I’ve emphasized sustainability at every level. In foundational courses, I educate students about the environmental impact of ceramics, including where materials come from and how landscapes are affected. Many are unaware of these realities and assume ceramics is inherently eco-friendly. While it can be, the issue lies in overproduction.

In another course, I ask students to bring seeds to give back to the earth—small acts that encourage critical thinking. My goal is not to instil guilt but to raise awareness. We discuss when firing is necessary, and often, students realize it isn’t, though I still ensure they experience the full process.

When exhibiting at a gallery, do you create the works on-site? How do you plan and set up an exhibition? Are your sustainable works for sale and where do they end up afterwards?

As an artist, I have the opportunity to engage with the public on various levels, spreading the message of sustainability. For instance, I invite people to bring in their old textiles and share the personal stories behind them. I also incorporate items from living spaces, exploring their personal significance. The community becomes part of the artwork, actively involved in its creation. One of my pieces, Triumphsäulen (42 Szenen der Gegenwart), was initially prepared in my studio but assembled on-site over several days. For larger international exhibitions, such as the Indian Triennale or Indonesian Biennale, curators typically give me about a month to prepare my work. However, for the Unicum Triennale, I only had two days, which required me to complete everything at my studio and quickly assemble the installation on-site. I enjoy these challenges—they push me to explore new ways of working. My approach varies depending on the context. When working abroad, I use local materials, which are returned to the community after the exhibition. The artwork is often deconstructed and recycled at the end of the show, aligning with my sustainable practice.

After 25 years of working with ceramics, I had a humbling experience at the Indian Triennale, where the clay slip was so sandy I struggled to work with it. It took me a month to understand how this new material “breathes”. I try to share this philosophy with my students—you are the ones who need to listen to the material. You are not the master of the material, it’s the other way around: clay is your master, and you need to listen to it and see what it can offer, and only then can you start to work.

I appreciate how you describe the material as the “master”. Traditionally, makers are expected to master their materials by perfecting techniques and avoiding mistakes. In product design, strict criteria must be met, which can limit the material’s potential. Once someone masters a technique, they often fall into repetitive patterns. While mastery doesn’t necessarily stifle creativity, I personally seek practices that push the boundaries of material exploration. Your work is a great example of this.

In my opinion, this is a form of self-censorship. We unconsciously follow rules, often for pragmatic reasons, producing work that meets public expectations or sells well. This limits creativity from the outset. It’s similar to how a journalist might self-censor under political or social pressure—such a journalist isn’t realizing their full potential. Instead, they simply work to meet expectations, leaving their true abilities untapped. It’s a waste not to utilize all the qualities we possess.

This is why, in my foundational courses, I teach all possible techniques. Even if students don’t end up using them, they need to experience the full process to understand what they’ll need in the future. Once they’ve learned the fundamentals, I encourage them to break the rules and find their own path.

I believe this programme structure supports conceptual exploration within ceramics. Traditional knowledge is essential—it teaches you what can be done. Once you understand what ‘s achievable, you can also explore what can be “undone”.

In the art world, we often find ourselves reinventing things that have already been discovered, either because we don’t invest enough time or because we lack information. Understanding a material’s full range of possibilities allows me to push its boundaries further. I draw on the expertise of past ceramic masters and continue from where they left off.

You were the creative director of the Dr. Hans Hoch Foundation and the Foundation of Sparkasse Südholstein in Neumünster, where you initiated the Ceramics Tandem programme. Now, as a lecturer, you work with students. You’ve thus always been able to observe artists and students during their creative processes. What is the most important lesson you’ve learned from this?

The residency programme was unique because it wasn’t a typical artist residency. It was intimate, with two artists working side by side in the same building where I lived with my family. Artists worked within existing infrastructure, becoming part of the household. It was a special environment.

What I learned from observing artists is the importance of letting go. Many artists struggle with wanting and needing everything to be perfect. I would think: be happy with the experience itself, the opportunity to be here and with knowing your work is part of this collection. Why exhaust yourself striving for more? Some artists would work day and night, pushing themselves to the limit. This relentless drive prevented them from truly enjoying the moment.

The key is to be present and let go—of the idea, the art, and the technical aspects. Those artists who allowed themselves to relax and let go of their expectations were the ones who benefited the most. Only then could they truly connect with their inner voice, their ideas, and the material. They also opened up to their fellow artists, discovering new collaborative possibilities.

This reminds me of my residency in Indonesia, where we had almost nothing. I had to face it, deal with it. Otherwise, you waste a lot of energy, but nothing changes.

This was my experience in Indonesia as well. I’d done research back in Germany, but arriving there, I had nothing. There were no materials. I’d have to wait for several days for a single 1.5 litre bottle of slip cast, and so I had to calculate how long it would take for me to get enough so that I could start casting. Situations like these make you think differently.

Reflecting on the Neumünster residency, I was fascinated to observe both young and experienced artists facing similar struggles. But I often wondered: is it worth becoming so consumed with these challenges that you forget to be present in the moment, to truly experience the process—both physically and mentally? Of course, it’s human to struggle, and not everyone can deal with these situations easily. People have certain expectations about how their work should progress and how it should look. When things don’t go as planned, it can be hard to cope with the reality of the situation.

One especially memorable and successful experience was with a group of students during an external residency I organized outside the university. We travelled together and held exhibitions, and through that process, we realized our collective potential. The group consisted of five individuals—painters, sculptors, all at different stages of their careers. But we came together around the topic of sustainability and the environment. We created a time capsule project, imagining a world 500 years from now, where nothing would be the same. We asked ourselves: what message should we leave behind for future beings? What if these future creatures or civilizations didn’t speak our language? The idea was to bury a message that could be universally understood, perhaps explaining why our civilization no longer existed, much like many ancient ones. We didn’t have definite answers, but this thought experiment united us as a collective.

This project led to an invitation to Documenta, one of the largest contemporary art shows in Germany and the world. It was an incredible experience for all of us.

How did you get to Documenta?

We were a group of five, and I truly believe in the power of collaboration—multiple minds are always better than one. That’s why I love working with others and building communities. One of my students was in Berlin on a residency, so we decided to visit him and use that opportunity to work on a joint project.

Our project became part of Documenta through the lumbung Indonesia, an Indonesian collective that organized invitations as a series of expanding rings—one group invited another, creating a growing network. Initially, it was somewhat controlled, but eventually, it became unpredictable. That kind of dynamic can either lead to collapse or to success, and in our case, it turned out well.

A partner, ZK/U Berlin, a centre for art and urbanism, helped transform an old house into a boat, reflecting our focus on resourcefulness. Artists powered this boat by pedalling, moving from Berlin to the Documenta site over two months. Someone always had to push the pedals to keep the boat moving.

The artwork we presented was a collaborative effort: a time capsule, a boat, and unique dining plates with messages and political imagery. We used these plates daily on the boat, finding joy in the different designs.

Upon arriving at the castle just in time for our performance, we invited the public to eat from the plates as if it were our last meal. Afterwards, we held a ceremony in which we buried the plates. Unfortunately, we found out that we lacked the necessary permission, and we only had an hour to complete the performance before the police would arrive. I was worried because, in a sense, I was no longer just an equal member of the collective. I do take on a different role when I teach, but at that time I was able to forget about it and to function as just another member of the group. We realized there were masses of people. It was too late to stop, so we asked ourselves what to do next. I told the group to check the dirt nearby, and we ended up near a palace. It wasn’t the smartest choice, but it was better than being by the river, where the police would have arrived immediately. The public was observing our performance and we continued with our ceremony. If the police would come, we’d keep our poker faces. But we were lucky; they didn’t show up.

The energy there was incredible. People, friends and strangers, were deeply engaged, choosing plates to place. Towards the end, my gallerist asked if she could buy a plate, and I told her she could, but only if she buried it. She agreed, and the whole experience left everyone in awe. The performance wasn’t just some silly game; everyone was fully immersed until the very end. That’s what made it special, more so than any prize or recognition. It was something beyond the usual academic setting.

When students apply to UdK in Berlin, they cannot choose Ceramics as their main course of study, but they can take it as an elective within their Fine Arts programme. How do you balance the technical aspects of ceramics with artistic expression?

They are definitely more free, in the sense that they don’t have any boundaries. When I arrived and took over the course, I completely restructured the programme, adding many projects that we implement at other institutions outside the university. The best part was the total freedom we had in creating our programme, allowing me to introduce something new each semester. I wanted to keep the programme fresh, both for myself and for my students. However, I quickly realized we faced a major challenge. I was at a great university, but the previous lecturer had a very hands-off approach, letting students do whatever they wanted without much guidance. I saw potential in this situation. Since nothing substantial was in place, I decided to focus my energy on the foundational courses for the first few years. I made these courses mandatory, ensuring that students couldn’t skip them. If someone came to me with a project idea but hadn’t completed the basics, I’d direct them to start there. This approach helped me manage the workload and prevented chaos. Without it, I would have been overwhelmed by students wanting to do ambitious projects without the necessary foundations.

In the first year, I doubled the foundational courses, offering them both in the morning and in the afternoon to accommodate as many students as possible. I knew that if I built a solid base early on, I could focus on more advanced topics later. The foundational course provided students with comprehensive knowledge, condensing what I’d learned in five years into one semester. I made it clear that, while not all of it might be needed immediately, it would be valuable later, especially if they pursued teaching. After these basic courses, students moved on to more advanced studies where we delved deeper into specific topics or practices. We also had open studio sessions where students who completed all courses presented their projects, and we created detailed plans together. This approach ensured they could work independently, but with a clear structure. Another issue I noticed was that gallery pieces often originality, relying too much on existing glazes. I started offering glaze courses to encourage students to experiment and create their own. We even established a glaze library with shared recipes available online, promoting global knowledge-sharing.

Ultimately, my approach is about deconstruction, not destruction. By breaking things down, I can create something new, which requires letting go of the old.

Your work aligns with contemporary and conceptual art, challenging traditional views of the medium. Given today’s ceramics scene, what’s your opinion of the current situation? How do you see the field evolving compared to a decade ago, particularly in the context of various biennial and triennial events? In Slovenia at least, the ceramics community often debates the value of ceramics as art. What’s your perspective on this?

I believe that question is outdated—ceramics is undeniably art. My work, while rooted in tradition, often incorporates humour and has a contemporary twist that makes it relevant to today’s world. The argument about whether ceramics qualifies as art is unnecessary; what we’re doing now is contemporary ceramics, and there’s no need to question it.

Regarding institutions like biennales and triennales, these events play a crucial role, but the focus should be on the present and future of ceramics, not on rehashing old debates. Ceramics, whether traditional or contemporary, shouldn’t be overanalysed. We’re making contemporary ceramics, and that’s it. I’m here now, not a hundred years ago, so why question it? When we bring up these discussions, it makes it look like we’re uncertain about what we’re doing, but that simply isn’t the case. I stand by every word I say and every piece I create.

It’s exciting when new talent emerges because our community, being small, often recycles the same energy and ideas. This stagnation can make the community feel insular and uninviting. If we identified as artists rather than just ceramicists, our perspective would expand, and the community could grow. We’d avoid the repetitive complaints about the same issues at every event and instead focus our energy on new projects.

As artists and educators, it’s crucial to continuously innovate and reflect on our work, yet many institutions resist change, sticking to outdated methods because it’s easier. But is this beneficial for the art scene and the community? Institutions have a responsibility to the artists and the public who fund these endeavours. They need to adapt and innovate, even though the changes might be small, to stay relevant and engaging.

For instance, when I joined a very traditional institution in Neumünster, it was largely unknown because it was so insular, only serving the interests of a few people. I realized the need to open it up and create something that spoke to a broader audience. Art shouldn’t be a solitary pursuit; it’s about eliciting reactions and interactions. Public participation is crucial to my work. My projects often involve the audience directly, making them co-creators. Such engagement can bridge the gap between traditional and contemporary art, making it accessible and relevant.

One project in Hamburg involved a terracotta carpet painted with traditional patterns. Visitors who walked on it unknowingly became part of the artwork, tracking the patterns through the gallery, which evolved over time. This process highlights the importance of audience involvement—they contribute to the art’s creation and feel a deeper connection to it.

Art should surprise and engage people, creating moments of realization and participation. This is a view that likely stems from my upbringing in socialist Yugoslavia, where community was paramount. My work reflects this idea, striving to connect the past with the present and to involve the public in meaningful ways.

Ultimately, my approach is about deconstruction, not destruction. By breaking things down, I can create something new, which requires letting go of the old. This freedom to continually renew is essential in my art and life.

By letting go of constraints and embracing freedom, I can create something new. If I hold on to my work, conserve it, or worry about preserving it, I can’t move forward or innovate. This freedom allows me to see potential in what might seem negative or challenging, and to find something positive in it.

Nothing is stable or fixed; there is no permanent form. This realization, combined with my experiences, has helped me understand the importance of the environment. Everything gradually came together, but also remained fluid and dynamic.

What is your relationship with the material itself? Sometimes you let the material take on a life and characteristics of its own, allow it to exist as it is. However, when you cover objects with it, the material often drips and doesn’t dry properly, suggesting you are controlling it. How do you view this process? When I see your work, it feels like every aspect is carefully thought out. Everything is meticulously planned down to the millimetre and matches exactly what was envisioned. Do you see this as controlling the material or as a form of freedom? What is your relationship with the objects and the clay?

When I work, I start with a clear plan and prefer to stick to it. Given my multiple commitments—projects, teaching, and family—I need to be highly organized to make art. I plan meticulously to ensure everything works out. However, I experience a different kind of engagement during exhibition openings. About five hours before the opening, I apply the final layer while the material is leather-hard—neither wet nor dry. At this stage, people can touch it, which is intriguing. Observing their reactions—sometimes akin to childhood curiosity—reveals a primal urge to interact with the material.

In the following two weeks, I relinquish control and let the material act on its own. This is the moment I truly enjoy. I don’t know where cracks will form or how the material will evolve. I provide a framework and then step back, becoming an observer. I document the changes and enjoy the subtle transformations, from colour shifts to the development of lines. This process of letting go and observing is what I find fascinating.

I agree. When something is shiny, there’s a strong urge to touch it. Your work, especially when it’s completely dry, creates a similar urge. It feels delicate, and I have this instinct to avoid breaking it. I appreciate how your work provokes this reaction. If I understand it correctly, your pieces invite interaction. For example, a sofa at the exhibition is meant for sitting?

Many people asked if they could sit on it, and the answer was yes. The work was designed to be engaged with, whether by sitting or touching. At one exhibition, I recall a visitor constantly touching the pieces, like a child. Eventually, he came to me saying “Look, I’m dirty because of you”, as if it were my fault that he got dirty from touching the pieces. I found it amusing because I’d been observing him closely, noticing how his touch was changing the work.

I documented this interaction, realizing that each touch left its mark, effectively transforming my pieces. It’s as if I had unexpected collaborators in the audience. I never instructed anyone to touch or handle the work; I simply allowed them the freedom to interact with it. If their actions changed or even damaged something, I accepted those consequences. My initial, intensive dialogue with the material happened during the creation process, but now the material communicates on its own with the public, independent of my direct involvement.

I guess I’ll be sitting on that sofa next time I see you work. laughter

It’s interesting because, while observing your installation, I felt a strange, contradictory sensation. There was a sofa that I could sit on, but it was also a dry clay art piece, making it seem untouchable. This created an intriguing moment of uncertainty for me.

I was unsure whether to sit on it or not. The humour of the situation was clear, but at the same time, I wondered how to interact with the piece. Should I engage with it or keep my distance? If I engage, I understand there might be certain consequences. If I don’t, I’m left with a sense of detachment from an everyday object that I would typically use at home. This tension between interaction and detachment is what continues to fascinate me about your work.

You asked about covering objects with clay and their patterns. For me, it was essential to gain an understanding of the background of these objects through interviews. I wanted to learn why these items were significant, not just about their surface details.

During an interview, a woman brought in a porcelain sauce set. Initially unsure about giving it to me, she eventually sat down to share its story. It turned out her parents had given it to her when she first left home for studies. As we talked, she realized the deep emotional significance of the object, which moved her to tears.

This experience highlighted a broader point: in our over-consumptive society, we often accumulate more than we need. Reflecting on our possessions, we might find that only a few truly bring us joy. My work aims to strip away symbols and patterns, making all objects appear the same, thus challenging the notion of material value and consumption. By covering everyday objects with clay, I remove their distinctiveness and force people to reconsider their relationships with them.

What do you do with the stories people share with you? You said that you know the personal story behind each object. Do you write these down?

Yes, I document them. If there’s an exhibition catalogue, I include them there. Otherwise, I still collect and keep them, thinking they may one day become part of a book or something similar. Everything I’ve published so far has gone into a catalogue, which I believe people find important.

For you, the creation of an artwork seems to begin well before you start touch the clay or cover the object with slip. It starts when you begin planning and searching for objects. So, when does your project truly begin and end?

My work often begins even before I start planning or selecting objects—sometimes a year or more before an exhibition, when I first discuss my ideas with the curator and visit the space. The venue and its history can be a trigger for my creativity. Once I know the exhibition venue, my mind starts planning everything—from materials to the overall concept.

What’s important to understand is that my work is a continuous process, it doesn’t have a clear start or end. Each exhibition leads to the next, with ideas evolving and transforming. For example, during my solo show in Hamburg, a visitor was so inspired by our conversation that she brought me a set of gold porcelain from her mother. This gift became central to a new piece that I did a year later, showing how my projects are always interconnected.

My work may appear minimal and understated, but it’s part of a larger process that never truly ends. The art continues to evolve, and the only question is whether we take the time to notice that and engage with it.

Kristina Rutar is an artist born in 1989 in Slovenia. She completed her studies in ceramics at the Faculty of Education, University in Ljubljana, in 2013. She continued her post-graduate studies in interdisciplinary printmaking at the E. Geppert ASP in Wroclaw, Poland. She mainly works in sculpting and ceramics, questioning the traditions of the two mediums. She received numerous awards and acknowledgments, and her works can be found in public and private collections. She lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia, where she works as an assistant professor of ceramics at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.