There is visible consistency in your creation. What was the starting point for your investigation with ceramic art?

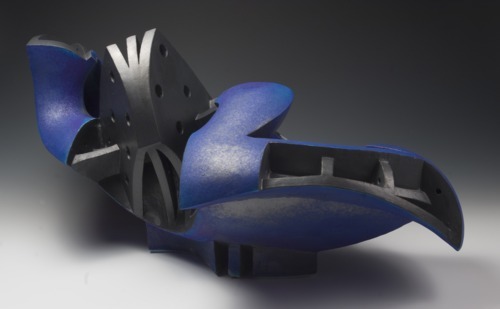

The starting for my works comes from the traditional vessel and understanding the primary elements in the design. I have taken the elements of the foot, body, and lip of a pot and applied them to more structural elements within my sculptural designs. Development of a language within these components has allowed the works to maintain continuity through the progression of forms. The works become more refined as I focus on transitions of lines and volume. Complexity in the structures is inspired by marine life, geological formations, buildings, bridge design, and armor. With the creation of all my works, I try to stay true to the inherent properties of the materials.

Your works reveal a very rigorous methodology. Tell us more about the process of constructing them. Do you make preliminary drawings?

I used to draw blueprints for my pottery and sculptures. But the works always seemed to lose something in the translation from 2D to 3D. I think the spontaneity of the sketch and energy never quite translated. Once I began using slump and drapes molds, I began to only sketch gestural drawings with ink. This allowed me take an idea (not a concrete design) and began to find new forms through exploring hidden lines within objects while only maintaining the idea of the gesture. I apply the gestural line I am looking for onto the X, Y and Z axis of the object in order to maintain flow and control of the entire three-dimensional space it occupies. I am working with a modular mold system, which allows me to create an inventory of parts to pick and choose from freely. This system allows me to maintain being in a “state of the art” while exploring new forms. The sculptures are hollow, and all have an inherent strength as I complete lines whether circular or elliptical, symmetrical or asymmetrical. Then I construct a lip on the vessels using armature, just like ribs in an airplane wing or a boat hull. The ribs create a template to be covered with slabs, which accentuates the forms I have already created. The tensile strength of this element keeps the hollow forms from warping or moving during the firing process.

Architectonics – Hull Improv, side view, 2011. White stoneware, slab built, 38”L x 18”W x 17”H, Cone 04 Oxidation

Tell us more about large scale fabrication. Taking the size into consideration, have you confronted with some particular technological problems?

I found through many accidents, the importance of the foundation you build on. There were many cracking issues early on in the high arches of the sculptures. I thought it was uneven displacement of weight that could be resolved by building additional supports that were fired with the works. But with continual cracking at the point of the supports I began reviewing the overall movement of the pieces throughout the shrinkage stages, from cone 04 to cone ten the problems were the same.

I have since figured out the most important component for success is in the shrinkage slab. My pieces are built on a piece of gypsum board and a 3-5 cm thick clay slab. The gypsum board has two strengths; it helps dry the shrink slab evenly and allows it to shrink evenly with little friction during the firing process. When fired to a range of temperatures the gypsum board can protect kiln shelves by catching any glaze accidents and as it is fired it breaks down consistently keeping the slabs from warping.

A second issue I deal with at large scales is in the firing process. I have witnessed that you can fire any scale and any thickness of work as long as you go slow for the important stages of the firing where out gassing of the materials occurs. I used to be terrified of quart inversion but realized that my issues were occurring during much earlier stages of the firing. I have since dramatically slowed down the preheating of the work and kiln. The most delicate stages are between 90 degrees Celsius to 400 degrees Celsius. As this is when physical and chemical gasses are released. The thicker or more complex the work the slower I go. My bisque firings are generally a 3-4 day firing. By slowing down these stages, the other benefit is that the kiln and all posts/bricks/shelves heat up more evenly and allow for more control of temperatures from top to bottom that can be very difficult in kilns that are over 1.5 meters in height. I have also recorded less fuel usage in this longer firing as it leads to a more efficient firing with preheating the kiln sufficiently.

Between industrial and handcrafted ceramics, where do you place your works? How do you relate to mass-production?

Between industrial and handcrafted ceramics, where do you place your works? How do you relate to mass-production?

My aesthetic has also been greatly influenced by mass production industries. I have been fascinated by systems and production practices in large-scale factories creating objects ranging from extruded roof tiles, slip cast figures and jiggered vessels. There is a visual power in both multiples of an object and the consistency of sharp details. I also find a great beauty in the molds themselves and maintain a vision that sees the objects as parts, not finished pieces. Though, the removal of the human hand from the object within most industries leaves the work lifeless. I have developed my studio practices by taking the elements of the industry that allow for efficiency in production but also allowing a freedom within the final designs. During construction, the sculpture itself becomes a mold for making other components of the piece. I enjoy making works that are one off and not designed for mass production while maintaining a balance with aesthetics related to machine-made objects. Through this process of the invention, the work is allowed to evolve continually.

What challenges you the most in ceramics practice?

“Learn to work within your limitations”, this was written on the wall at the University of Montana when I was in undergrad. I would look up and read it everyday, but I think it took years for it to settle in and for me to gain an understanding of the importance in the statement. Limitations seem to have a negative connotation, but I have found in my studio that parameters are strengths. Parameters can be determined by factors such as: the physical environment (studio space, kilns, materials) and/or our own body (physical disabilities, mental states, accumulated skill sets & knowledge). The challenge within my work and goals in ceramics has been to seek out creative and innovative solutions that allow projects and concepts to become a reality.

Architectonics – Nautilus Improv 1, side view, 2011. White stoneware, slab built, 26”L x 23”W x 33”H, Cone 04 Oxidation

What are you currently working on? Tell us about your future goals.

Recently I have taken a position running the ceramics program at Northern Michigan University. Most of my focus has been on the development of new curriculum and establishing an international study program. The program will have yearly trips to such facilities and studios as Gaya Ceramic and Design in Bali, Indonesia; Da Wang Cultural Highlands Park in Shenzhen, China, Pottery Workshop in Jingdezhen, China. With this also brings the expansion of the classroom/glaze facilities and experimental kiln construction for ceramics students to take part in kiln design and firing.

In my studio, I have been expanding my modular mold system with the next evolution of forms. Revisions of the molds are allowing for more efficient construction and also helping me get a little closer to finding a good one. The works have been focused on trying to give tangible form to gestural lines. With the experimentation of the installation of sculptures, I have been honing in on the vision of the works and realizing the next body of work is contained within the negative spaces. The dialog between sculptures contains elements of form and design that are missing in the final objects and has become the focus of the new works.

By Andra Baban

Published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 2.

View Brian Kakas’ profile on Ceramics Now.

Visit Brian Kakas’ website.