You are one of the most assiduous ceramic artists in the world, with hundreds of exhibitions over more than thirty years. Why did you choose this career path?

If by career path you mean, “why did I choose to be an artist?” I was one of those guys who always knew that they wanted to be an artist. I honestly cannot remember a time that I did not draw. I remember drawing in kindergarten. I took my first oil painting class with my mother at age 7. I identified with being an artist my whole life, so the path was “written on the wall” so to speak. Also, times were different thirty years ago when I graduated from UC Davis. The word “career” was subject to interpretation. I remember that all I wanted to do once I graduated was to do whatever I needed to do to keep making art without needing to work a “regular” job. This was a huge factor because if one wants to make art their whole life they need to be creative in terms of how to do that. As a consequence, I learned how to make a career instead of only making a lot of things.

When did you realize that ceramic art was important for you?

My relationship with ceramics has always been a double-edged sword because I originally didn’t identify with ceramics or sculpture. In the beginning, I used clay to make a better painting!

My formal undergraduate art education at American River College in Sacramento and later California State University was as a photo-realist painter, this was the art movement of the time and all my teachers were photo-realists. I, although formally trained with all the exactitude and precision of a realist, was extremely frustrated. I wanted my paintings to be more expressionistic, spontaneous and “rule breaking”, but the training and dictum of “painting the right way” was so hardwired that I needed to change the very physicality of the painting’s object-ness. I realized that when addressing the white geometric canvas, specifically when the paintbrush approached the edge of the canvas, my gestures would be stilted and choked. I was too intimidated by its rigidity. I remember thinking that if I was too influenced by the edge, then I needed to change that edge.

Meanwhile, at California State University, at the opposite side of campus from the painting lab, was the ceramic department. Two of the professors there were Peter Vandenberge and Robert Brady, both were UC Davis alumni and former students of Robert Arneson. It was by watching them make their clay sculpture and witnessing the ways that they both treated the clay as a mud that did their bidding, that first attracted me to it. This was an epiphanous moment. I remember thinking that clay was the perfect replacement for canvas on stretcher bars. Upon returning to my studio, I slung a number of clay slabs and stretched them on the floor and then fired them, resulting in “bisque canvases” of non-geometric shapes, like a stack of so many pancakes. Then, using oil paint, I reacted to the silhouette of the shape by painting-in imagery that would co-relate to the swells and dips of the randomly shaped ceramic slabs. In my eyes, clay was a remedy, not a historical material. Ironically, I later dispassionately applied to graduate school at UC Davis to study ceramics sculpture under Robert Arneson knowing that I was competing against real ceramic artists who knew more about clay than slinging slabs, which literally was all I knew! It was those first experiments with oil paintings on ceramic slabs that got me into graduate school. My education of clay as a material didn’t start until my time with Robert Arneson. The one thing that I loved about clay was how I now could make things that could distance me from the confines of oil on canvas and, as a result, lifting the weight of the ‘History of Painting’ off my shoulders. When I thought of ceramics, I didn’t see “History” or “Tradition” or “right and wrong”. In fact, I didn’t even think of it as “ceramics”, I thought of it as clay that you made hard. To me the material was only material, and because I came to it through the back door it represented to me to be absolute freedom, a kind of sanctuary from the rules of painting and, as a result, pure invention.

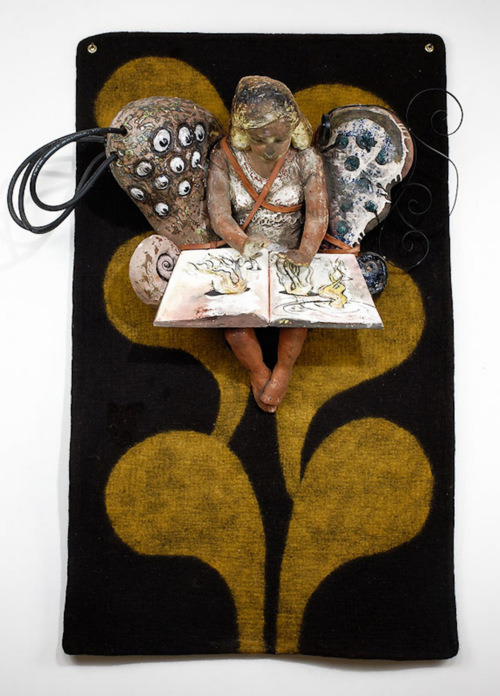

Song of a drunken angel, 2007, ceramic, glaze, iron rod, rubber hose, leather, Iranian felt, 60” x 48”x17.”

You accepted the challenge of imagining and constructing figurative works. What’s your process of thinking a new series of works or a new piece? We know that drawing is also important for you.

“Accepted the challenge” is a funny way of putting it. That’s like saying, “accepting the challenge” to eat your favorite foods, but it’s also understanding that figuration has a major history within The History of Art, which can be daunting. I, on the other hand, could not see myself as any other kind of artist. Figuration is my first-best passion; anything else would be a waste of time. I wonder what it would be like to be born twenty years earlier and faced with a world of Abstract Expressionism and how I would need to “triumph” over a world of non-imagery. This is why one of my favorite artists is Philip Guston.

In terms of “what is my process of thinking” a new piece or series, this is a question that requires thinking! The first thing in my head is that it comes from many places…in fact it comes from everywhere! When I think of myself, objectively I see someone who is like a walking puzzle, each piece fitting into other pieces, yet each part independent with its own curiosity. By saying that I see myself objectively, it’s similar to being a voyeur of my own movements. I will witness then judge my decisions and maybe become curious about that person and help understand what needs to happen next. This sounds a bit like a split personality, but I believe that this is a way of tracking one’s own process and is mandatory for understanding a diagonal growth in one’s personal art.

That being said, I see my work as a working soup; gathering aspects of influence, being influenced by curiosities, questions that occur through observations, observations of beauty, the beauty of a pose, the posing of questions, the questioning of media mixed, the mixing of metaphors, the metaphors of things that are most important, the importance of things that create passion, the history of passion and personal definitions of passion that are different from history’s, and the joy of understanding that we are in history now and not in a “post-history”. The biggest chore is to make this soup full bodied and experiential and not a concoction of repellant meaninglessness.

Now in terms of figuration and your question, I see the figure in sculpture as a base, much like a painter needs something to paint on. The figure is my canvas. It is my start. I find that I think in terms of metaphor and symbolism. I am a student of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and those who are their descendants, and although I use fired clay as a dominant material, I respect all media and understand that certain symbols and their portrayal are best exposed when they are attached to specific material. In other words, there is a time for glass, rubber, wood, iron, string, cloth, mirror, turtle shell, bone, when attached to ideas of the unknown, ideas of openness, flexibility, defensiveness, warmth and desperateness, age and youth. If I need to speak about weightlessness, ceramic is not the right thing to use, but ceramic is the great communicator. It can take on so many different shapes and looks, it can diplomatically be the go-between other materials. When I see a visual devise that inherently can have many ways to explore a specific visual combination (perhaps a theme of a figure who carries a heavy load) with a variety of archetypes (man, woman, old man, young child etc) carrying various metaphors (fire, inner ears, a bag of intestines [labeled “a bag of intentions”]) then a series of drawings begin. These drawings will explore techniques of realism or cartoon. These may become paintings and eventually a wall or floor sculpture…and that’s a whole other game.

What is the role of figurative in your works? You express so many emotions that threaten to erupt into reality; you can feel them just by looking at your works.

The “role” of the figure is to always be present for the sake of the viewer’s ability to relate to the work on a personal level. There are many works of art in history that are difficult to relate to because the role of the figure is missing, for example the works of Joseph Beuys. His performance work is amazing because it includes the figure. It makes a connection from the personal to the universal. We get it. We understand the poetry. It is more difficult to understand the importance of “fat and felt” when the figure is absent. Of course, in those pieces, the figure is not really absent; the figure is present in the understanding of the metaphors, yet it’s a more difficult read for those of us who love figuration. Joseph Beuys is an artist who changed my life in art as far back as my undergraduate work in Sacramento. His theory of “material” is still a vertebra to the backbone of my understanding of what I need to remember when I make art.

But if one looks at the pieces that I make, you will often see the figure in pre-occupation. The figure just isn’t posing, just being beautiful or ugly. It is involved in a certain task, or it may be holding something important in a way that reminds us of other things held in that manor. The expression on the face is paramount to the point being made. Without these aspects to the figure, the sculpture will very seldom leave my studio.

Nouns & Verbs, 2007, ceramic, Egyptian paste, mirror, wire, wood, 31” x 31” x17”. Collection of the Colorado University Museum in Boulder.

Where do you get your inspiration from and what motivates you?

I get my inspiration from many sources, but inspirational events show themselves from the beckonings of personal needs and concerns, which I have many!

There is always my love for the female figure, and the challenge to portray the inexplicable as well as the obvious, but that being said, there is the need to understand the archetypes of gender and age, and so the subject of the piece will dictate the archetype. A beautiful nude can be completely wrong where an aging Pinocchio is appropriate, but more important than that is the face of the figure. If there is a face, the viewer must read it. And expression is everything. It tells us whether the subject is cynical or romantic, alert of daydreaming, meditating or simply asleep.

There is my need to understand things that I know that I will never fully understand like the ancient practice of alchemy, yet I know that I have a connection with alchemy in a deep way, so I will insert imagery, postures, and symbols in provocative places in order to empower the piece and hopefully enlighten the artist. The idea of empowering the piece in divisive fashions sits large with my agenda. I love poetry, yet consider myself a novice, so I will insert a passage from Federico Garcia Lorca or Chaucer on the skin of a figure and place it upside down so that the figure can look down and read it. It’s not for us to read, because we are the voyeur.

I’m very interested in visual devises that trigger ways of thinking, such as visual or conceptual duality. Passion and irony are two subjects that work well together, and is a staple in my work. I try to discover new metaphors that I have never used before. This is the power of found objects and mixed media. I make a distinction between these two subjects, one has the luggage of past usage, and the other has inherent energy. In terms, of sculpture, there is the issue of making wall work and new ways of seeing its limits and creating new solutions. I try to find new ways of structuring formal balance and visual dynamics in my work by looking at other things that balance, such as bonsai trees, flamenco dance film stills, and Calder sculpture. Then there is the point of making visually interesting work. Simply put, if the work isn’t provocative enough for viewers to approach and stay interested enough to bother investigating, then what does anything else matter?

Front cover of Ceramics Now Magazine – Issue One

Tell us about your plans.

I am currently making about four different series of work at the same time, including a series of oil paintings on wood panel. I would like to be able to make sculpture and painting at the same time. The fact of the matter is that I have always described myself as a sculptor who thinks like a painter. After thirty years, I realize that it’s time to make paintings again. I’ve been enjoying this new phase, but it takes a lot of time. I’m making my wall work that’s a continuation of “the Question of Balance” series as well. I also am working a series of sculpture that are mutant painting/sculptures. These works are seriously strange, and at this point, very experimental. These pieces are a result of me posing the question, “If my work is described as sculpture that speaks in the language of painting, then what would painting that speaks in the language of sculpture look like?”

In the “next” future I will show at John Natsoulas Gallery in Davis, California and Mason Murer Gallery in Atlanta, both being shows of new painting. And on an exciting note,I have been invited to be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at Colorado University Museum in Boulder. This is still a few years away. Other than that, I’m hording all the new sculpture and exposing them all at once “somewhere down the road”.

I realize that I needn’t worry about what I make, as long as I see it as growth. If I make something that doesn’t have some new way of thinking in it, then I’ve just imitated myself. I know how to go into my studio and make another ”Arthur Gonzalez” sculpture; I don’t need to do that. I’ve had friends that point at another artist and accuse that artist of imitating me. I don’t care about that, just as long as I don’t do it! I know that when I enter my studio everyday, I have one “have to”, I have to find something new, and I have to find freedom. Ever since graduate school I remember a quote from Meret Oppenheim. “No body gives you freedom; you have to take it.”

Arthur Gonzalez received his MFA degree at the University of California at Davis. He studied under Robert Arneson. Manuel Neri and Wayne Thiebaud. He is an internationally exhibited artist with over 35 one-person shows in the last 25 years. He has received many awards, including two Virginia Groot Foundation awards,and an unprecedented four-time recipient of the National Endowment of the Arts award. He is a tenured professor at the California College of the Arts in Oakland, He also has been awarded many residencies including the Pilchuck Glass School, and the Tainan University of Art in Taiwan. Gonzalez advises his students to rid themselves of the process normally associated with ceramics, get past things that are supposedly bad technique (like epoxy in cracks), colve problems creatively and remember spirit when making work.

By Vasi Hirdo.

Published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 1 (Print Cover).

Visit Arthur Gonzalez’s website.

View Arthur Gonzalez’s profile on Ceramics Now.