Your work with ceramics has been active only in the last three years. What did you do before that? Tell us about your first experience with ceramics.

Well, my mother was a potter, starting back in the early 70’s, and so when I was a teenager I was exposed to clay through her work. She had a studio in our basement, with a wheel, kiln, glaze mixing area, etc. I tried throwing on the wheel back then, but I didn’t really connect with the craft aesthetic or the making process during that time. I was more interested in playing music and adventuring outdoors than working with mud.

Somehow thirty years went by before getting my hands back in the clay again. I ended up studying engineering and enjoyed a twenty-year career in the computer industry (designing graphics chips for companies such as Pixar, Silicon Graphics, and nVidia). It wasn’t until a little while after my mother passed away that my wife Liza had the idea of paying homage to her creative spirit by taking a raku class at our local adult school. Pull pieces directly out of a red-hot kiln and drop them into burning sawdust? …sign me up! It was fun performance art, but it was the building process that really drew me in. I started hand-building and designing systems to create forms that reflected my own sensibilities. More classes followed, and within a couple years I left the virtual world of computer engineering and was spending a lot of time in the clay studio. It was refreshing to be working with such a physical material and in a process where every piece created embodies its own unique identity.

You usually work with soluble metal salts, which give impressive shapes and patterns. How do you make the pieces?

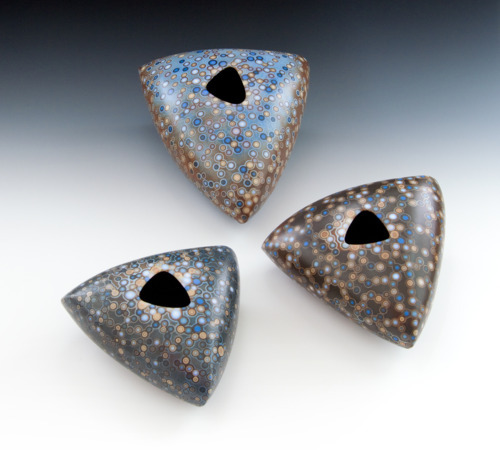

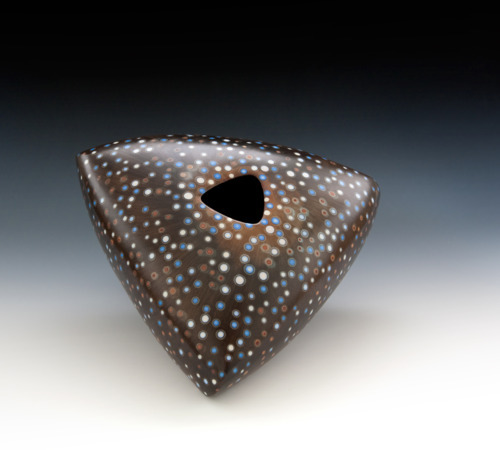

I may have been influenced by my experience in computer graphics, where you can render all sorts of interesting objects composed of intersecting curved surfaces, but early on I wanted to get away from the radially symmetric forms that come about from working with the wheel. So I learned about slab construction and ended up making a series of special hump molds (by pouring plaster into stretchy fabric suspended through triangular cutouts in plywood) to shape the clay. These molds enabled me to construct forms out of asymmetric parabolic curved surfaces, which had immediate appeal. My basic process is to shape, and then join these surfaces together to make my rounded vessels. The arcs in these pieces are designed to fit the sweep of my hand as I burnish the surface by rubbing with a smooth stone. For now, I enjoy working in a scale that fits easily into the hands, with forms that feel like waterworn stones.

I first learned about the soluble metals through a friend at the studio who took a solubles workshop from the American potter Gary Holt. Later I contacted Gary (who works locally in Berkeley), and he kindly shared with me a bunch of really useful tips on how to work with these chemicals. Fortunately, there is an encyclopedic tome on the process, written by the amazing Norwegian ceramist Arne Åse. I found a copy through my local library and quickly read it cover to cover. I started experimenting with the solubles in 2008, and it took nearly a year to get some basic proficiency in the use of these hazardous materials.

Is it technologically difficult to work with soluble metal salts, or do you find it easy?

And I thought engineering was difficult! For me, it’s still quite challenging to work with the solubles. Beyond the obvious issues of working with these highly toxic metal compounds, the fact that you can’t see what your finished piece will look like until after the firing takes some serious testing to pull off. I add food coloring to some of the solutions (which burns out in the kiln) just to be able to see where I have painted them. My early work experience as a chemistry lab technician is serving me well here.

It’s a huge help to be collaborating with fellow ceramic artist, Liza Riddle, who also works with the solubles. We’re still discovering some of the large number of variables that determine the final colors and halo effects that are possible.

The same solutions can produce radically different results based on such factors as clay type, how the piece is dried, firing temperature, etc. I find it essential to run a lot of tests and keep detailed notes to have any chance of achieving a deterministic outcome. Even with this approach, there are still many surprises when opening the kiln!

Have you tried any other materials and techniques, for example, raku firing?

I started with raku, and my aversion to shiny surfaces led me to try a number of non-glaze alternative firing techniques: pit, saggar, and barrel firing. In a nutshell, these processes have in common the fuming of metal oxides that are then deposited and bond with the clay surface. I found the results highly variable and somewhat difficult to control. So it seemed to me that one should be able to achieve better predictability through the use of soluble metals that are painted directly on the bisqued clay. I still sometimes work with a smoke firing process that many call “naked raku”. This allows the layering of drawn or random smoke patterns on top of pieces previously fired with the solubles.

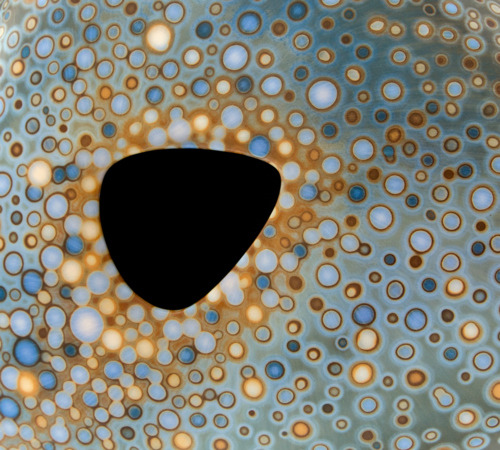

Vessel Detail (m57) – 12.5”w x 4.5”h – View his works

Tell us about how it’s like to be an emerging ceramic artist.

The whole experience has been extremely gratifying. One thing that was unexpected at the outset is the wonderful community of potters, sculptors, and ceramists that we’ve gotten to know over the past several years. It’s really a welcoming and supportive group, which gives me the feeling of being part of a larger creative collective. And through Facebook, we are connecting with more creative spirits in far corners of the globe (like Romania!)

What are you working on next?

A few months ago I took an excellent workshop from Heather Mae Erickson on mold-making and slipcasting. I think this opened up some new avenues for me. My current focus is to perfect some of these techniques and slipcast my forms. It’s quite exciting to work with some new processes that present some different constraints. I can see that these will lead my work in some new directions. One of my favorite quotes is from Johnny Cash who said, “Your style is a function of your limitations, more so than a function of your skills”, and this seems especially true with the processes I’m involved with. So far, my work has been largely vessel-based, but in future, I expect to branch out into some other areas.

What advice has influenced you the most in your career as a ceramic artist?

I’ve always thought that anyone who has found their passion and has an opportunity to pursue it is extremely lucky. So my advice is to “follow your bliss” as Joseph Campbell said. It’s quite likely to lead you through a satisfying life.

But also, balance this out by acquiring a few additional money-making skills! From what I can tell, those who make a decent living as a full-time ceramic artist are few and far between…

“The process of working in clay is a grounding experience that focuses my attention in the present moment, but also is a tangible thread that connects across time with twenty thousand years of ceramists who preceded me.

My work is an exploration in shape and pattern, using the enclosed vessel as the underlying form. These vessels are constructed from asymmetric curved surfaces that project a unique contour with each viewing angle. The interior space is intentionally hidden, leaving the contents to the imagination, metaphorically containing perhaps hopes, dreams, or spirits. These rounded shapes are meant to be held and, when set on a flat surface, gently rock before coming to rest at their own natural balance point.

My approach is to combine ancient methods of stone-burnishing and earthenware firing with computer-aided shape design to produce talismans that fuse traditional and modern aesthetics. Surface markings are created by painting water-soluble metal salts on bisque-fired clay. These watercolors permeate the clay body and become a permanent part of the surface when fired. I have a strong affinity for intricate abstract patterns, ones that can’t be fully comprehended with a single glance, an invitation to in-depth exploration.

These ceramic forms echo the geometries of nature: waterworn stones, shells, seed pods, expansive desert landscapes, the Milky Way on a moonless night.” Mark Goudy

By Vasi Hirdo.

Published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 1.

Visit Mark Goudy’s website.

View Mark Goudy’s profile on Ceramics Now.