Before starting a career in ceramics, you studied Biology. In relation to your line of work, how would you characterize the relationship between Biology and Ceramics?

I believe my study of biology helped create the artist I am today: one that works by questioning what surrounds me, and by creating objects based on observation in a very systematic manner. Artists, like biologists, work from direct observation and immersion in the environment around them, and are forever attempting to interpret this world.

Both groups employ creative means to achieve this. I grew up on a farm in Southern California, one my family had farmed for four generations, surrounded by this natural world that was under the direct manipulation of the human hand to serve human needs. I believe I was drawn to study biology in college because growing up immersed in this agrarian landscape and was incredibly interested in the idea that we, as humans, have this ability to define, control, and use the natural world that surrounds us, yet we also have an imperative responsibility as a species to maintain this world.

In my final semester in college, I took a ceramics class, the first art class I had ever formally taken. I was immediately overwhelmed by the questions I found artists asking, by the responses that they drew from their audience, and the simple fact that they were using dirt, one of the most basic components of the natural world, to create. This type of communication and way of thinking drew me in, and I decide to change the direction of my life completely. I found that my voice was much more attuned to express my concerns of the livelihood of the natural world through the means of art than through my study of biology.

In the studio today, I find myself working in much of the same manner as I used to in the biology lab: trying to find the answer to a particular question. I also recognize my history as a student of biology in my draw to clay’s ability to be manipulated at all levels of its creation, whether it’s in the mixing and altering of a slip, or in the potential of atmospheric firings. I use this characteristic of clay as the basis of communication in my works.

You use unconventional techniques in very interesting ways, like unfired earthenware and wax. Tell us more about these methods and the creation process.

The medium of clay itself creates a very heavy material metaphor. Artists, I believe, are drawn to it for its malleability, its ability to record the touch of the human hand, and the sense of permanence it retains once fired. Unfired clay, especially at the bone-dry stage, is incredibly fragile, and ephemeral; it can be dissolved or broken down immediately. The impermanence that clay retains at this stage-struck me as incredibly meaningful, and I thus employed it to convey the meaning that I wished for in my work.

In my piece “What I See, What I Saw,” am speaking of three different landscapes I have experienced at one physical locale: one I lived in as a child, one I imagined as a child, and how I see the landscape existing today. The 2000+ roses in this work are made of unfired earthenware. They embody the namesake of the ranch I knew as a child, the Rose Ranch, and their arrangement suggests the fields of grain that once grew there. Wax, historically used as a preserving agent, holds these forms in this transient state; just how I hold my memories of this landscape now lost to me. By placing these fragile objects on steel rods that act as stems growing out of the hundreds of plywood house forms, I finally present the landscape as it exists today, covered by tract housing and shopping malls. What results in the contrast of the placement of these incredibly fragile objects paired with these industrial materials are a reflection, an observation, and a conjuring, all combined to form one landscape.

Your works are physical expressions of metaphors. Are some of these metaphors deliberately revealing pro-environmental messages?

By creating works that speak of landscapes that no longer exist, I am directly speaking out against what I see existing there today, yet I understand and acknowledge the need for this change as the human population continues to grow at an astonishing rate. What I find at the core of my desire to speak of this in my work is really my own search for the answer to this question: What can we do about this inevitable change, and how can we do this in a more positive way, one that considers both the human idea and need of home, and our reliance as a species on our natural surroundings? I openly intend for my works to speak of memory and loss in regards to the now suburban landscape that blankets much of what used to be rural lands, but I do try to do this somewhat subtly, by stopping short of very direct pro-environmental statements. I admire artists that can work with very straight political or environmental messages, but the intention behind the majority of my work is to present more of a questioning, asking the viewer to question what they see around them, and perhaps see the potential they each possess to participate positively in this change.

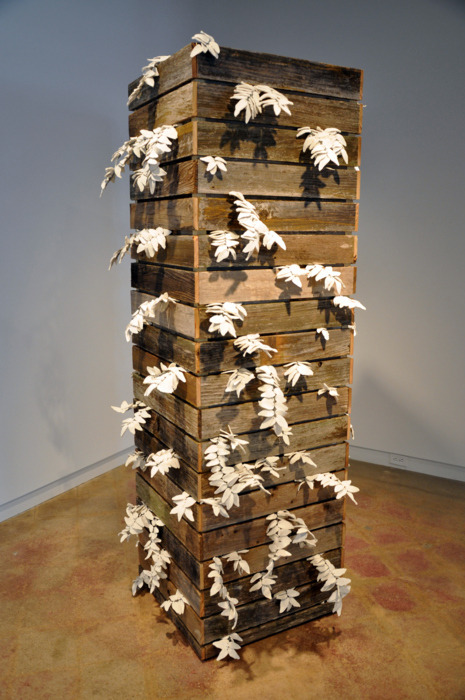

Roots, 2010, earthenware, tree roots, 5’h x 18”l x 5’d

You are also an instructor of art at the Temple College. How do you find the time to work both as an artist and instructor/teacher? Do students give you strength?

Time is an incredibly valuable commodity for any artist, and as an instructor, time in the studio often is overtaken by time in the classroom. My studio time is limited to my weekends during the school year, but I can immerse myself in my work during those valuable breaks. Working at a community college, I have a very dynamic classroom at all times: students from all walks of life, of every age and with amazingly varied amounts of experience. This leads to wonderful discussions and discoveries, and I honestly learn something new from my students every single day. I do my best to show them that I lead this sort of double life as an educator and as an artist, and I include them in this experience as much as I can. I attempt to bring a sense of community into the classroom by often working alongside them as they create their works, and by recruiting students to work with me as studio or installation assistants. Temple College has been incredibly generous to my students, my work and myself by sponsoring my travel and my students’ travel to numerous exhibitions across the country. This allows these students exposure to the functionings of the art world itself while also supporting my career as a studio artist.

You have an upcoming show in 2012, entitled “Marianne McGrath: New Works”. What can you tell us about it?

This show will be at the Las Cruces Museum of Art in New Mexico in August of 2012. It will include a new 200 square foot version of my work “What I See, What I Saw,” two large wall pieces comprised of small porcelain objects and various other materials that will talk about the growth and change of rural America, and a dozen or so graphite drawings based on my observations of the landscape that surrounds me. The drawings are a new endeavor for me, but one that I am excited about.

What inspires you?

Oh, so much I can directly recognize, and so much I can not: landscapes in which I have lived, traveled through or imagined; the human idea and need for home; the intangible and fleeting characteristics of memory and loss; the visual and physical patterns that occur in nature versus those patterns that arise from the hand of man; the endless potential of the medium of clay itself; the opportunity to communicate universally without saying a word… This question is very difficult for me to answer simply, probably difficult for anyone one that creates, and I believe that is the core reason we all continue to make: if we knew the answer to this question, knew exactly what we were looking for and what caused us to look for it, we would be there, there would be no need to wonder, and there would be no more reason to ask. I am thankful that I find the need to ask every single day.

By Andra Baban

Published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 2.

View Marianne McGrath’s profile on Ceramics Now.

Visit Marianne McGrath’s website.