By Daria Melnikova

In early September 2023, basking in the cool shade of a terrace in Gojōzaka, near Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto, I treated myself to a lacquer box of sake ice cream, a much-needed break after visiting the retrospective show “The Sōdeisha Group: An Era Born Out of Avant-garde Ceramics” at The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. After traveling to venues such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Gifu and the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Arts, this illuminating exhibition recently concluded its tour at the Kikuchi Kanjitsu Memorial Tomo Museum, leaving a lasting impression on audiences across Japan and beyond. As I perused through the exhibition catalogue—an omiyage from the museum—I felt intrigued by this group of ceramic artists who disrupted the traditional Japanese pottery scene between 1948-1973. As I read, my mind kept wandering back to those artists who actually gathered together here in Gojōzaka in a literati-like atmosphere enjoying each other’s company while sipping on sencha and sake, engaging in lively conversations ranging from literary discussions and tea ceremonies to philosophical debates about art.

Gojōzaka is renowned for its numerous pottery workshops that line the hilly path to Kiyomizu Temple. Since the early 5th century, the area around Kyoto has cultivated a distinctive style of pottery beginning with the earthy gray-blue Kofun ware and evolving into the refined ceramics favored by the imperial court during the Heian era (794-1185). The tradition of tea ceremonies during the Muromachi (1336-1392) and Momoyama (573-1615) periods further enhanced Kyoto’s ceramic artistry. Influenced by Zen aesthetics, simple yet expressive forms like Raku ware, characterized by its hand-molded construction, emerged. To meet the increasing demand and diverse preferences of the urban population during the Edo period (1615-1868), Kyō-yaki pottery was developed, encompassing tableware for dining, incense burners for ceremonial use, flower vessels for arrangements, and tea utensils for the tea ceremony. This brief overview only hints at the depth of history and craftsmanship found in Gojōzaka’s pottery. Yet, it highlights the weight of tradition and the enduring continuity that confronts those daring to challenge it. Despite this, a group of young Japanese ceramic artists rose their banner shortly after World War II.

1. Formation of the Sōdeisha Group

Amidst the chaos of rebuilding post-WWII, the art world was buzzing with new ideas and experimentation that sparked a new wave of avant-garde across Japan. In Kyoto, this spike had been reinforced by a revolt towards the conservative aesthetics established by Japan Fine Arts Exhibition or Nitten. Specifically, avant-garde ceramicists challenged the traditional techniques and designs of tea utensils and flower vessels, including the shape of a tea bowl or chawan. In 1946, a group of young ceramic artists formed Youth Ceramics Group to break free from the authority of Nitten. Initially, they shared a common goal of embracing a more experimental approach. However, among artists there were burgeoning ideological differences and search for individual expressions. In the fall of 1947, a pioneering avant-garde ceramics group emerged in Kyoto: Shikōkai. Among its founding members was the remarkably young Hayashi Yasuo (b. 1928), only 19 years old at the time. Hayashi’s groundbreaking work Cloud (1948) is arguably recognized as the first piece of avant-garde ceramics in Japan.

The following year, 1948, saw the formation of another influential group dedicated to revolutionizing Kyoto’s pottery scene: Sōdeisha. Founded by Yagi Kazuo (1918-1979), Kano Tetsuo (1927-1998), Yamada Hikaru (1923-2001), Matsui Yoshisuke, and Suzuki Osamu (1926-2001), Sōdeisha set out to push the boundaries of clay as an art form. Sōdeisha would become one of the most vanguard groups in Japanese ceramics. Yagi Kazuo’s statement set the tone for their collective vision:

In the aftermath of war, the world of art needed the refuge of alliances to escape its inner turmoil. Yet now, it seems, that provisional role has come to an end. The early bird, kicking off from the forest of illusions, seeks its reflection only in the spring of truth. Our bond is not a “dreaming hotbed,” but life itself under the bright light of day. We dissolved the Youth Ceramics Group and formed Sōdeisha anew with this very intention.1

This symbolic manifesto outlined their artistic beliefs and philosophical principles, as the group emerged from a time of chaos and sought to redefine art’s role in society. The group set itself apart from utopian ideals, emphasizing a realistic perspective grounded in everyday life. Calligrapher Ayamura Tanen, who lived close to Yagi in Gojōzaka, suggested the name of the group.2 The inspiration for the name came from the phrase qiūyǐn zǒu ní yìn (蚯蚓走泥印), which describes the patterns created by earthworms crawling on mud.3 The inauguration of Sōdeisha took place in September 1948 at a department store gallery in Osaka. A friend of Yagi Kazuo’s father arranged the space at no cost, providing the young potters with a platform to showcase their work. The exhibited pieces reflected the artists’ dual interests: on one hand, they drew inspiration from white Korean ware from the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) and the Cizhou kilns in China (active from the 10th to 14th centuries); on the other, they incorporated motifs inspired by modern Western artists such as Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Joan Miró (1893-1983).

These ceramics, blending traditional methods with innovative approaches, paid homage to celebrated historical styles while creating something uniquely contemporary. This fusion was evident in works like Yagi Kazuo’s “Vase with Sunflower Design” (1947, now in the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto) and Yamada Hikaru’s “Vase with Scratched Pattern, Persimmon Brown Glaze” (1947, housed in The Museum of Fines Arts, Gifu). Both pieces exemplified the group’s approach of merging traditional techniques with modern aesthetics.4 In contrast, Suzuki Osamu’s “Green Glazed Vase” demonstrated a bolder approach to form, pushing the boundaries of conventional ceramic design. This diversity in styles within the group highlighted the individual artistic voices emerging within the Sōdeisha movement, each contributing to the evolving discourse of modern Japanese ceramics.

2. Mr. Samsa’s Walk and the Birth of Objet Ceramics

In December 1954, Yagi Kazuo unveiled his groundbreaking work Mr. Samsa’s Walk at a solo exhibition in Tokyo’s Form Gallery. Art critic Yoshiaki Inui hailed this piece as the first objet ceramics of commemorative significance in postwar Japanese art.5 In this peice, Yagi experimented with the potter’s wheel, using a unique technique of throwing and reassembling pieces in unconventional orientations, in other words, overcoming the wheel. The resulting circular form, adorned with dozens of hollow tubes projecting at various angles, evokes a complex network of arteries, defying conventional ceramic aesthetics. The sculpture’s unconventional form drew inspiration from Franz Kafka’s surrealist novel The Metamorphosis, specifically the character Gregor Samsa, who undergoes a startling transformation into a giant insect. This literary allusion resonated deeply within postwar Japan’s intellectual circles, where themes of alienation and existential angst found fertile ground. Since the 1940s, despite American occupation censorship, Japanese intellectuals had been grappling with Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophy and Existentialist ideas, exploring complex notions of self, body, and identity.6 By integrating abstract and surrealist elements, Yagi created a profoundly expressive and conceptual piece. Mr. Samsa’s Walk embodies a physical transformation of pottery’s established boundaries, exemplifying Sōdeisha’s mission to transcend the limitations of traditional ceramics and mirroring the avant-garde’s collective mindset.

The origin of the term “objet ceramics” has sparked various theories. According to Yagi, he didn’t purposely come up with the name but rather it emerged organically during a conversation at a Kyoto bar with members of the avant-garde art scene. In response to someone asking what they were working on, Yagi quipped, “Objet ceramics!”7 This phrase was popularized in the postwar ikebana world, where unconventional flower arrangements using deadwood and everyday items were referred to as “objet flower arrangements.” Yagi found humor in this and adopted the term for his free-form ceramic pieces that defied traditional utility. However, this concept did not necessarily align with Marcel Duchamp’s idea of transforming ordinary objects into artistic pieces.8

3. International Exhibition of Contemporary Ceramic Art in Japan

The Tokyo Olympics 1964 marked a significant moment for Japanese ceramics with the exhibition “International Exhibition of Contemporary Ceramics.” For the first time, Japan hosted a global showcase of ceramic art, with exhibitions traveling to major museums in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nagoya. The event’s executive committee, comprising members from diverse backgrounds including Nitten, the Japan Craft Association, Mingei movement, artists, academics, and museum specialists, curated a wide-ranging collection of styles and forms. Notably, the exhibition featured a significant number of female artists, with Tsuji Kyō (1930-2009) standing out as Japan’s sole representative. The Japanese works, while constrained by tradition, presented a more austere and somber aesthetic compared to their American and European counterparts, which often displayed a broader range of expression but sometimes lacked distinct cultural identity.9 Despite criticism from some quarters, including ceramic artist Yanahihara Yoshitatsu’s claim of “defeat,” the exhibition catalyzed a new wave of creativity in Japanese ceramic art. Particularly, it galvanized the Sōdeisha movement.

As art critic Yoshiaki Inui characterized the works of Yamada Hikaru and Kumakura Junkichi as “return to clay,” highlighting their evolution towards more expressive forms.10 For example, YAMADA Hikaru’s Tower and KUMAKURA Junkichi’s Spirit of Wind ’67 testify to their striking individual expression and bold, free-form designs. These works marked the maturation of Sōdeisha’s distinct style, which emerged from Kyoto’s cultural landscape but also drew inspiration from the dynamic sculptures of Isamu Noguchi. Yamada’s Tower particularly stands out, evoking Noguchi’s Humpty Dumpty (1946). Yet, its architectural design incorporates elements reminiscent of a pagoda—a nod to Yamada’s heritage as a Buddhist priest. The piece’s greenish glaze pays homage to traditional stone pagodas, lending a sense of historical continuity. However, Yamada subverts conventional symmetry by tilting the structure, resulting in an irregular, flattened heptagon. The roof eaves, typically associated with pagoda architecture, extend outward to form leg-like projections, enhancing the dynamic and unconventional aesthetic of the artwork. Yamada’s innovative approach extended to his technique as well. He reimagined the traditional method of clay forming clay, tatara, typically used to create horizontal plates. Instead, Yamada positioned these thinly stretched plates vertically, joining their sides together to form a rectangular shape. This unique technique became emblematic for his Tower series, further distinguishing his work within the avant-garde ceramic movement.

KUMAKURA Junkichi’s Spirit of Wind ’67 exemplifies his mastery of form and glaze. With a background in architectural design, Kumakura imbues his pieces with a sense of scale and volume that translates through his expertly crafted forms. The central body of the mass is shaped into a voluminous sphere, while a flattened, planar form envelops it. The plastic material molded around the central mass creates a dynamic tension between the bulging volume and the constrained and compressed surface. Kumakura’s choice of a yellow-brown Irabo glaze highlights the warm beauty of the clay, reminiscent of ancient Japanese ceramics like Bizen and Shigaraki. The surface’s contrasting smooth and porous qualities reinforce clay’s natural properties, achieved by dotting the top element with azalea branches. This pattern echoes the bunjin-gasuri design, an elegant indigo-dyed kasuri cotton fabric from Kurume. The deliberate misalignment of warp and weft patterns is considered a refined aesthetic, hence why it shares its name with bunjin, meaning literati or scholar.11 Channeling Chinese artist Muqi from the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), who allegorically represented literati in his Six Persimmons painting, Kumakura creates his own interpretation of the scholarly ideal.12 The Japanese title “fūjin” (Spirit of Wind) alludes to the refinement of a literati or poet, reflecting Kumakura’s broad intellectual interests spanning ancient to modern art. Art critic Inui Yoshiaki noted Kumakura’s expansive knowledge, which extended beyond ceramics to encompass a wide range artistic disciplines.13 This voracious intellectual curiosity adds depth to his artwork, transforming Spirit of Wind ’67 into a multifaceted exploration of form, tradition, and scholarly ideals.

4. Sōdeisha’a Legacy and Contemporary Ceramic Art

Creativity, originality, and uniqueness, found in the works of Sodeisha, constitute the essence of modern Japanese ceramics.14 The cultural significance behind the group’s ability to infuse functional forms with deep meaning struck a chord with a new wave of Japanese ceramic artists. In an interview, Tanaka Tomomi (b.1983; Hyogo, Japan) and Sakai Tomoya (b. 1989; Aichi, Japan) shared their inspiration and evolving understanding of the distinction between art and craft in the context of ceramics.

Initially, Tanaka Tomomi was taught to view paintings and sculptures as forms of self-expression, while crafts were seen as purely functional objects. However, as Tanaka delved deeper into her own artistic journey, she began to question this binary separation, noting that both sculpture and craft involve creating three-dimensional works using similar materials like clay or glass. Similarly, she observed mass-produced bowls and cups in stores that appeared handmade but yet lacked the unique touch of true craftsmanship in ceramics. Though the artist was drawn to the medium of ceramics, she didn’t want to limit herself to solely creating cups or other functional objects. Her chance encounter with a collection of works by the Sōdeisha group was a pivotal moment. Tanaka recollected, “I was astounded to discover that people had been doing exactly what I aspired to do long ago. This revelation gave me the confidence and clarity I needed to fully pursue my artistic aspirations. After realizing how aligned my approach was with theirs, I made up my mind to study ceramics at university.”15 The discovery of Sōdeisha’s work sparked a newfound perspective for Tanaka, inspiring her to embrace ceramics as a medium for expressive art. She meticulously molds and layers thins folds of clay or lamellas onto the core of each piece in her creative process. This laborious method takes a minimum of two months to complete one piece. In her Fleeting Cloud (2012), Tanaka transcends mere representation of nature, instead capturing a sense of emotional turbulence. The whirlwind of thin clay layers evokes a delicate, almost vulnerable quality. This piece exemplifies Tanaka’s skill to infuse abstract forms with profound emotional resonance.

For Sakai Tomoya, the philosophies of the Sōdeisha ceramic art group—especially their challenge to transform vessel forms into independent, sculptural objects—have been a liberating influence on his creative process. The group’s exploration of the potter’s wheel not merely as a tool for shaping functional ceramics, but as a medium to express inner landscapes, resonated profoundly with Sakai’s artistic approach. As Sakai himself explained, “My creative process similarly uses the wheel as a medium to probe and express my unconscious mind and deep-seated memories. The ReCollection series is born from various contemporary sensibilities, including anime, manga, films, and cultural elements that have shaped my identity.”16 Sakai’s fascination with the potter’s wheel as a vehicle for uncovering personal memories and emotions can be traced back to his time working in an auto parts factory, after high school. There, he discovered the beauty of rotational metal forms, an appreciation that carried over into his ceramics practice. Through the wheel, Sakai creates abstract objects that exist in the liminal space between the known and unknown, the concrete and the abstract. His process is meditative, revealing fragments of submerged memories that materialize into sculptural forms, challenging viewer’s perceptions of identity and form. For the artist, his work represents an intimate dialogue between himself, the clay, and the wheel. Thus, Sakai not only invites viewers to explore his personal memories but also encourages them to engage with their own, fostering a deeper connection between the self and the material world.

The legacy of the Sōdeisha group continues to shape and inspire contemporary ceramic art, as seen in the works of artists like Tanaka Tomomi and Sakai Tomoya. Their ability to blend tradition with personal expression speaks to the enduring relevance of Sōdeisha’s avant-garde vision. By challenging the boundaries between functionality and art, Tanaka and Sakai have each, in their own way, expanded the potential of ceramics as a medium for self-reflection and storytelling. Thus, Sōdeisha’s pioneering spirit perpetuates the ongoing conversation about the place of ceramics in contemporary art.

This research trip to Japan has been generously funded by the Louis Frieberg Center for East Asian Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

s

Daria Melnikova Solignac is an art historian and consultant with a focus on modern and contemporary Japanese art. She obtained her Ph.D. in Art History of East Asia from the University of Pennsylvania. Melnikova has taught at Columbia University in New York City and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She has been awarded numerous fellowships, grants, and awards, including the Louis Frieberg Fellowship, the Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Research Fellowship, and the Mary Griggs Burke Postdoctoral Fellowship. Currently, she is a Research Associate at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, where she is working on her book manuscript on Japanese avant-garde art.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Captions

- HAYASHI, Yasuo. Cloud. 1948. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

- YAGI, Kazuo. Mr Samsa’s Walk. 1954. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

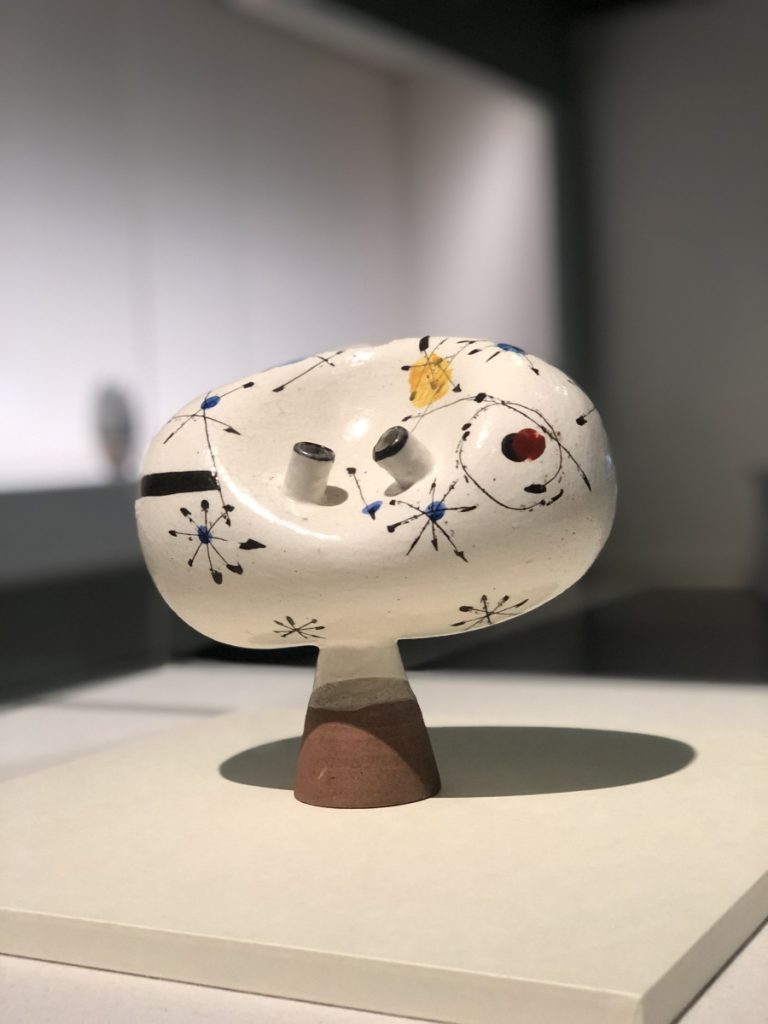

- YAGI, Kazuo. Jar with Two Small Mouths. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. Photo: Daria Melnikova-Solignac

- YAMADA, Hikaru. Tower. 1964. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

- KUMAKURA, Junkichi. Spirit of Wind ’67. 1967. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

- TANAKA, Tomomi. Fleeting Cloud. 2012. Photograph: HAYASHI Tatsuo.

- SAKAI, Tomoya. ReCollection series. 2021

Footnotes

- Fujii Keiyuki, “Sōdeisha 2,” Season of Innovation and Avant-garde 18, December 2, 1988.

- Ibid.

- Cantonese connoisseur Hu Zhiheng (1877-1935) described this trompe l’oeil porcelain in his book Commentaries on Porcelains by Yinliu (Yinliuzhai shuoci). For more information see: Chih-en Chen, “Fooling the Eye: Trompe l’oeil Porcelain in High Qing China,” Les Cahiers de Framespa 31 (June 2019), http://journals.openedition.org/framespa/6246.

- For more information about these works, see: Louise Allison Cort, “Crawling Through Mud: Avant-garde Ceramics in Postwar Japan,” The Studio Potter 33, no. 1 (December 2004), https://studiopotter.org/starting-out-vol-33-no-1.

- Fujii Keiyuki, “Sōdeisha 5,” Season of Innovation and Avant-garde 21, December 23, 1988.

- See Doug Slaymaker, “When Sartre was an Erotic Writer: Body, Nation and Existentialism in Japan after the Asia-Pacific War,” Japan Forum 14, (2002): 77-101.

- Fujii Keiyuki, “Sōdeisha 5,” Season of Innovation and Avant-garde 21, December 23, 1988.

- See Amiko Matsuo, “Suzuki Osamu, Sodeisha, and Ceramic Identity in Modern Japan,” Ceramics: Art & Perception 96 (June 2014): 3–7.

- Koyama Fujio, Yoshida Kōzō, Fujimoto Yoshimichi, Tsuji Seimei, and Ōkōchi Nobutake, ed. Nihon Tōji Kyōkai (Japan Ceramic Society), “International Ceramics Exhibition: Roundtable Discussion,” Tōsetsu 139 (October 1964).

- Inui Yoshiaki, “Return to Earth: Kumakura Junkichi and Yamada Hikaru,” in Gendai no Tōgei (Contemporary Ceramics), vol. 16 (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1977), 158.

- Orimono Senshoku Jiten Kankōkai (Dictionary of Textiles and Dyeing), 3rd ed. (Tokyo: Senmon Tosho, 1953), 753.

- Muqi’s Six Persimmons is housed in the Juko’in subtemple of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, Japan. Kumakura was most likely familiar with this masterpiece.

- Kuroda Ryōji, Gendai Tōgei Zukan (Illustrated Encyclopedia of Contemporary Ceramics), vol. 1 (Tokyo: Kōgei Shuppan, 1967).

- In her book Theory of Contemporary Ceramics (2023), contemporary art historian Todate Kazuko identifies these three characteristics of modern ceramics.

- Tanaka Tomomi, “Contemporary Ceramics in Japan: Interview with Tanaka Tomomi,” interview by Daria Melnikova, April 17, 2024, scholartists, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bv0WFm8cwzw&t=448s.

- Sakai Tomoya, email to author, September 27, 2024.