Article by Debra Sloan

In the province of British Columbia, on the far western edge of Canada, the ceramic culture was initiated through international immigration during the 20th Century. BC is one of the few places in the world where the indigenous people did not develop a ceramic technology.Instead, the First Nations were and remained masters of wood—their source of all things practical and expressive. Ceramic knowledge had to be imported, and a local audience is still in the process of being cultivated. The variability of the BC ceramic practice reflects the waves of immigration that have and continue to flow into this region. Equally various are the recipients – a polyglot of information meeting a polygon culture.

Processes and traditions that have taken humanity millennia to develop were, upon importation to BC, freely re-interpreted and quickly disseminated. BC’s first known potter was a Swede, Axel Ehbring, who immigrated shortly after WW l equipped with training in traditional pottery. A handful of other immigrants, from the UK, Belgium, Hungary, Italy, USA, Japan, Korea and China, brought their ceramic knowledge to BC between and after the World Wars. By 1955, the Potters Guild of British Columbia (PGBC) was founded. Unlike European Guilds, the PGBC was never intended to establish specific technical or aesthetic standards. Instead, during the 50s and 60s, the Guild founders sponsored many internationally renowned teachers to present workshops, such as: Edith Heath from California, Alexander Archipenko from New York, Olivier Strebelle from Belgium, Carlton Ball from the University of Illinois, Kyllikki Salmenhaara from Finland, and Marguerite Wildenheim via USA, trained in Germany, Harry Davis from New Zealand, and Michael Cardew from England. The PGBC and the North-West Ceramics Foundation (NWCF) have continued in this learning tradition with an active Speaker Series and sponsoring numerous workshop opportunities.

Ron Vallis, Stoneware vase, 2007, Stoneware, approx. 8.7 x 3.9 inches / 28 x 10 cm.

Sam Kwan, Salt glaze jar, 2008, Stoneware, 21 x 12 inches / 53.4 x 30.4 cm. Photo by Norah Vaillant.

Jackie Frioud, Set of 3 Canisters, 2013, Stoneware, Nichrome wire, Largest piece: 5.1 x 7 inches / 13 x 18 cm.

Kinichi Shigeno, Mountain Pine Beetle Cup and Saucer, 2012, Porcelain, cobalt, 7 x 4.7 inches / 18 x 12 cm.

Brendan Tang, Manga Ormolu Ver. 5.0-k, 2011, Ceramics, mixed media, 18.5 x 23 x 13 inches / 47 x 58.5 x 33 cm.

Mariko Patterson, Willow High Tops, 2010, Low fire white clay, decals, paint, 9 x 7 inches / 23 x 18 cm.

With these artists came the knowledge of Asian traditions, the Bauhaus School, and the Arts and Crafts and Modernist art movements. Another significant influence in BC ceramics, as elsewhere, was that of Bernard Leach. During the late 50s through to the 70s six potters from BC studied with Leach, bringing his philosophy back to BC initiating a surge of independent studio potters province-wide. The works of Wayne Ngan, Sam Kwan, Ron Vallis, and Jackie Frioud show a variety of influences of the Leach Mingei traditions. [images 1, 2, 3, 4] Leach had been affected by all of these art movements, but was most profoundly affected by Soetsu Yanagi, author of The Unknown Craftsman and founder of the Mingei, a Japanese folk art movement. Yanagi himself had been influenced by the philosophy of the British Arts and Crafts movement. The works of Kinichi Shigeno, Brendan Tang, and Mariko Patterson [images 5, 6, 7] are examples of how European and Asian philosophies have come full circle in British Columbia and are expressively hybridized.

By the 1940s, some education in ceramics was available at the old Vancouver School of Art [VSA], and by the 50s at the University of British Columbia as well as at small private pottery schools. Presently there are four universities in BC, and there are many colleges and art centres offering classes. The works of Don Hutchinson, Darcy Grenier, Debra Sloan, and Evan Ting Kwok Leung [images 8, 9, 10, 11] are diverse examples of four artists who were self-taught or initially trained in BC. In the early 70s author and artist Robin Hopper [image 12] with his knowledge of many technologies, emigrated from the UK and began teaching in Ontario and then in BC. Emily Carr University of Art and Design, ECUAD, replaced the VSA, and offers a BFA in ceramics, and has commenced a graduate programme. The ECUAD ceramics programme was led by Tam Irving and Sally Michener [images 13, 14] for over 20 years, and is now headed by author and artists, Paul Mathieu, Justin Novak and Julie York [images 15, 16, 17]. Another avenue for learning has been to pursue post-graduate degrees or residencies abroad. Artists Ian Johnston, Alwyn O’Brien, Liza Au, and Ying Yuen Chuang [images 18, 19, 20, 21] are among the many who have travelled and studied in the UK, Europe, Australia, USA and Asia. There are a few residency opportunities in Canada. In BC, the Museum of Anthropology is about to host Lisa Henriques [image 22] for a six-month residency. Medalta, in the province of Saskatchewan, has an extensive international residency programme. The Banff Centre in the province of Alberta has an established ceramic residency and this year is partnering with NCECA. Les Manning, one of the jurors for the 2013 1st Cluj Ceramics Biennial, and a participant at the 9th Symposium in Cluj-Napoca, was instrumental in establishing both of these residencies. Red Deer College also in Alberta, has an established Artist in Residence programme.

Don Hutchinson, Mythicals, 2010, Stoneware clay, 13.8 x 3.1 inches / 35 x 8 cm.

Darcy Grenier, élever relevé, 2009, Porcelain, 11 x 11 x 20.5 inches / 28 x 28 x 52 cm.

Debra Sloan, Momentum Illusion, 2014, Midrange red clay, coloured skips and rebar wire, 21.7 x 22 inches / 55 x 56 cm.

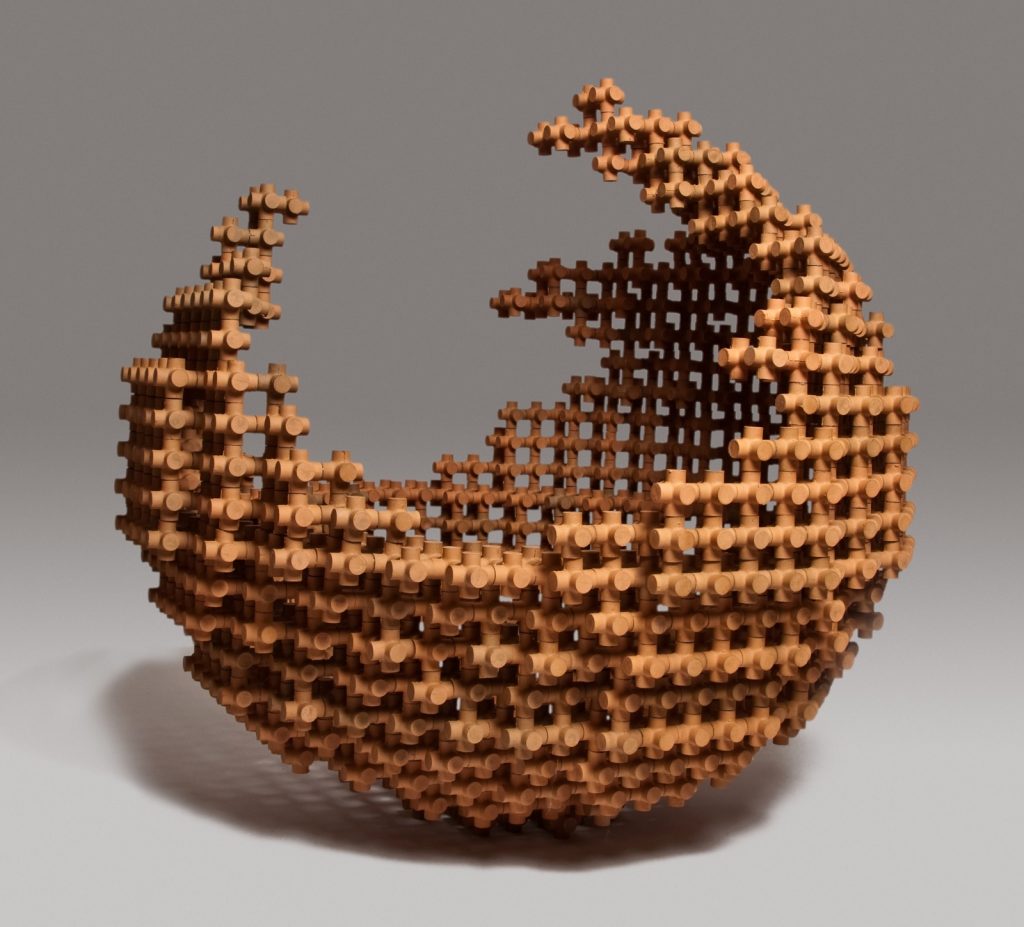

Ting Kwok Leung, Harmony III, 2011 (Collection of New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum, Taiwan), Clay, oxidation firing, 51.2 x 51.2 x 48 inches / 130 x 130 x 122 cm.

Robin Hopper, Fluted Agateware Bowl, 2005, Three-colored porcelain, cobalt, 6.7 x 3.3 inches / 17 x 8.5 cm. Photo by Judi Dyelle.

Tam Irving, Rocking Bowl, 2007 (Collection of Surrey Art Gallery), Ceramic, underglaze slips, ash glaze, 15 x 15 inches / 38 x 38 cm. Photo by Ken Mayer.

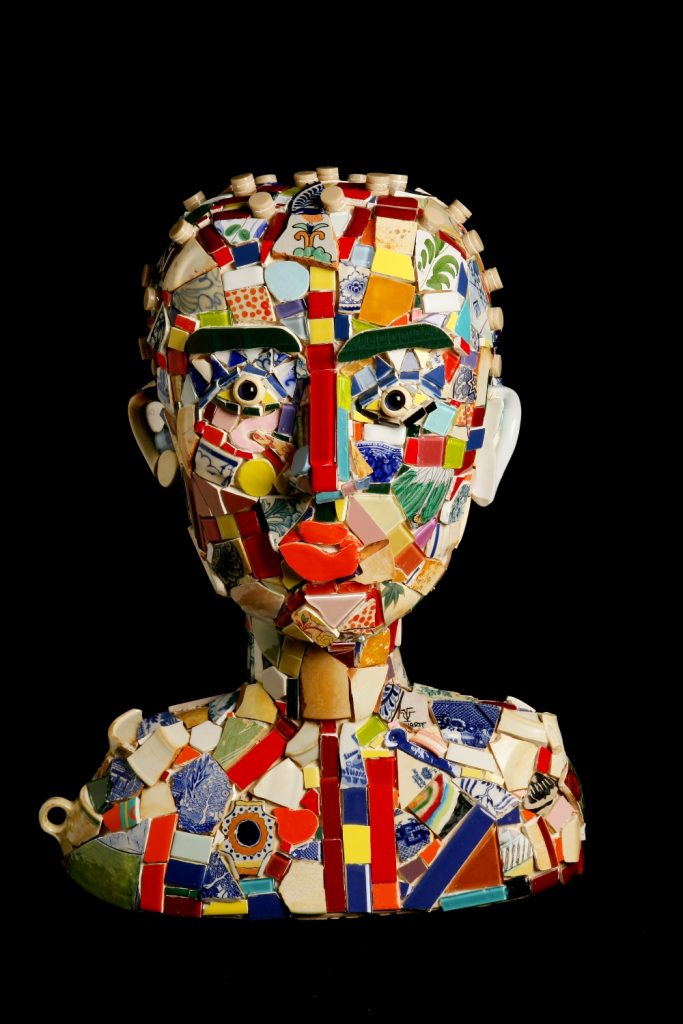

Sally Michener, Pieced Together Man #1, 2011, Clay mosaic, 23.2 x 18.1 x 11.8 inches. Courtesy of The Jonathon Bancroft-Snell Gallery-Galerie.

Paul Mathieu, Morphed Photo Vases, 2009, Porcelain, photo transfer, paint, H 13.8 inches / 35 cm.

Justin Novak, Disfigurine 32, 2003, Porcelain, 13 x 9.8 x 16.1 inches / 33 x 25 x 41 cm.

Julie York, White on White, B. Wood, 2013, Paper, 14.1 x 9.8 inches / 36 x 25 cm.

The absence of an indigenous ceramic culture has had cultural consequences. Public institutions did not have a framework in place to study ceramics, and the general populace did not have a tradition of supporting and using local handmade ceramics. Consequently public galleries, museums and other institutions have been slow to find a context for or to support the ceramic practice. Very few regional institutions have BC ceramic art in their permanent collections, and ceramics is rarely included in exhibitions of contemporary art. In terms of awards or grants, there are only two government grant agencies in the region, the BC Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts. The B.C. Achievement Foundation has an annual award and the NWCF funds an Award of Excellence. Progress is slowly being made as ceramicists are actively striving for their art practice to receive greater recognition and integration, and to promote a culture of collecting and connoisseurship. Several Guilds and Co-ops support small galleries and shops largely through the tremendous initiative and work ethic of their members. One outcome of the limited cultural support in BC is that many artists seek exhibition, residency and teaching opportunities outside of BC and Canada, and it is interesting to note how many have achieved international recognition.

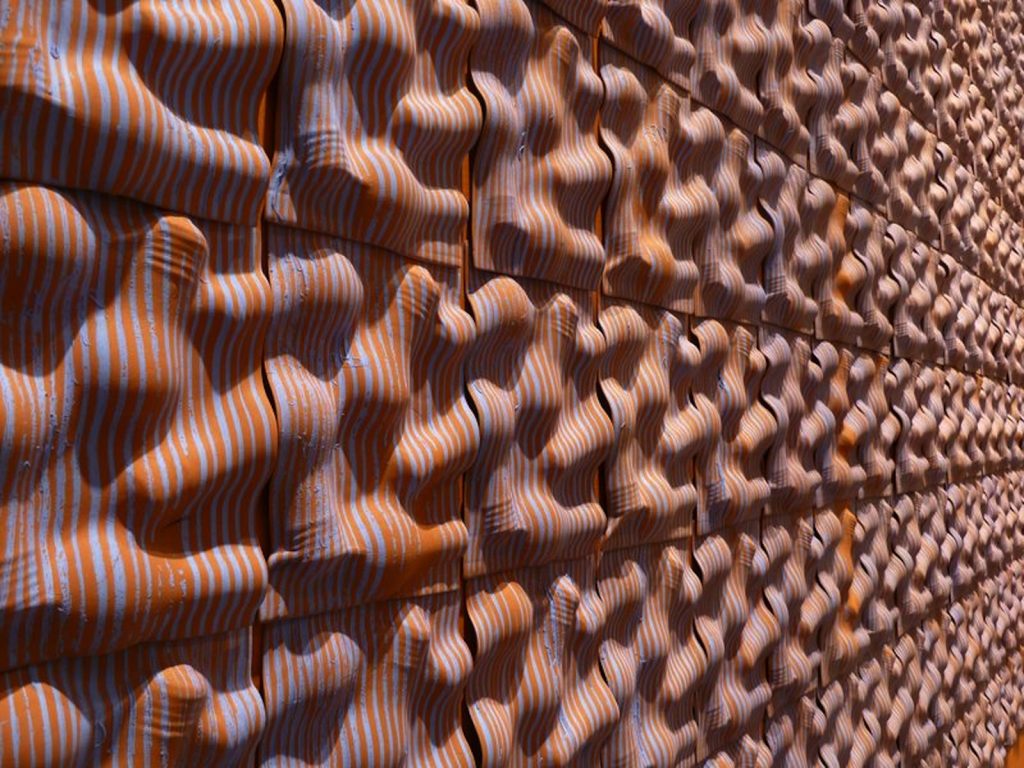

Ian Johnston, Between the Lines / Georgia (detail), 2012, Terra cotta, 10 x 24 feet / 3.05 x 7.32 m.

Alwyn O’Brien, Stories of Looking, 2010, Porcelain, 13.8 x 17 x 7.9 inches / 35 x 43 x 20 cm.

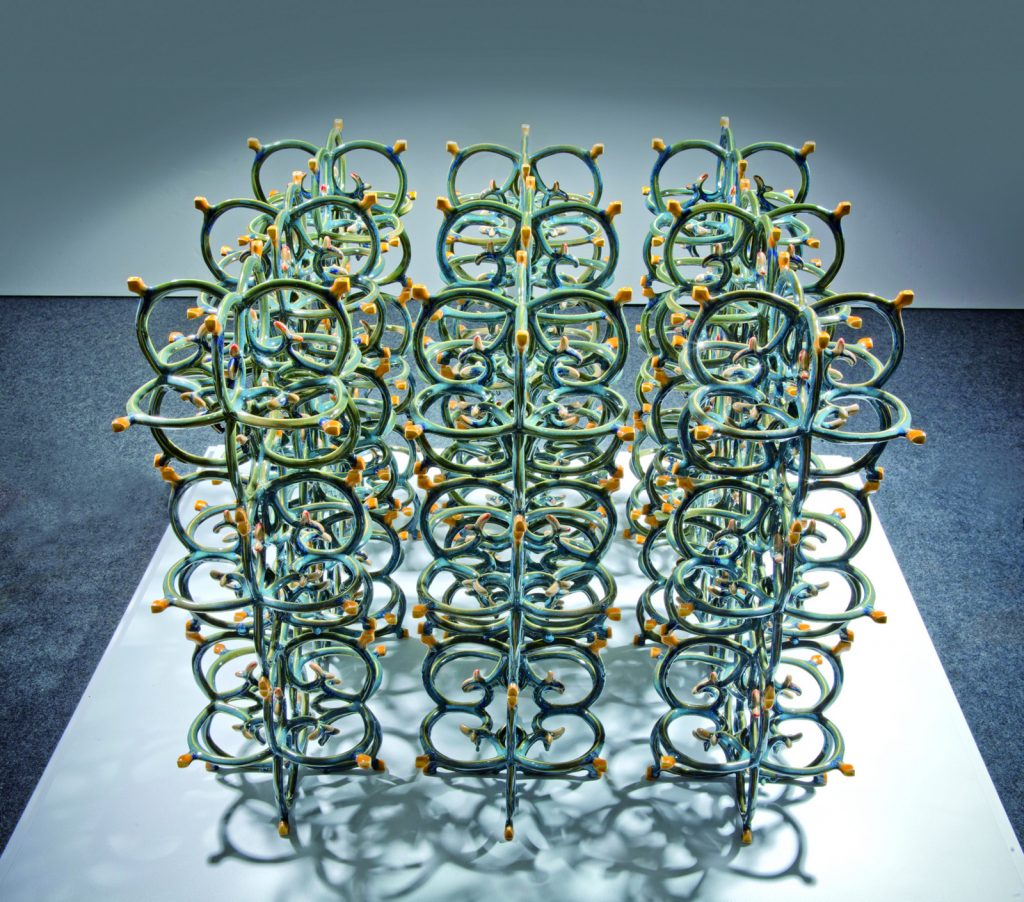

Eliza Au, Axis, 2011, Stoneware, 36.2 x 36.2 x 36.2 inches / 92 x 92 x 92 cm. Photo by David Stevenson.

Ying Yueh Chuang, Flower Series, 2011, Commercial vintage fabric, wood, Chinese imperial porcelain, 119 x 104 x 4.7 inches / 302 x 265 x 12 cm.

Lisa Henriques, Untitled 35, 2010, Porcelain, terra sigilatta, 16.1 x 13.4 x 16.1 inches / 41 x 34 x 41 cm. Photo by Ken Mayer.

There are the other factors, quite apart from the cultural aspects mentioned above that have an effect on the BC ceramic practice. BC is a “new” region—the most recently populated through immigration on the North American Continent. Immigration to BC was encouraged only when the railway across Canada was completed in 1881. The previous alternatives were – after 1869 when the trans-American railway was completed – to travel by land or sea the 1500 kilometers from San Francisco to Vancouver, or to endure the perilous months-long sea journey around the Cape Horn. The next factors are what Canada is known for—distance and weather. Canada itself is over 7000 kilometers from sea to sea. In BC, from east to west, one travels nearly 1000 kilometers, and over 2500 kilometers north to south. Consequently the distances between the small towns and cities in BC are vast, making transport and travel expensive and time-consuming. In BC the distance factor is combined with daunting geography and capricious weather. The massive Rocky Mountain Range acts as an isolating barrier between BC and the rest of Canada. The Rockies made building the railway a deadly enterprise, tragically costing the lives of uncounted Chinese and other immigrant labourers. Eighty years later the Rockies also challenged the progress of the Trans Canada Highway, which was only completed in 1962. In addition, within the province, there are the Selkirk and the Coastal Mountain ranges. Vancouver itself, where most of the BC population lives, is situated in the Southern corner of BC, beside the Pacific Ocean. Outside of this rainy and temperate coastal region, winter weather and those mountain ranges combine to prevent easy travel from October to April. Coastal BC is a northern rain forest and is often referred to as the “Wet Coast”. Clouded skies, rain, and blue-grey mists prevail an average of two hundred days a year. The powerful effect of these landscapes and environment can be seen in the works of Cathi Jefferson, Mary Fox, Laurie Rolland, and Rachelle Chinnery [images 23, 24, 25, 26].

Cathi Jefferson, Mountain Forest, 2012, Stoneware, soda firing, 26 x 15 inches / 66 x 38 cm. Photo by Teddy McCrea.

Mary Fox, Crawl Glaze Bottle, 2006, Blue terra sigillata, white crawl glaze, 8.3 x 6.3 inches / 21 x 16 cm. Photo by Janet Dwyer.

Laurie Rolland, Black Arthropodal Series, 2013, Ceramic, 47.2 x 3.1 x 16.5 inches / 120 x 8 x 42 cm.

Rachelle Chinnery, Yunomi, 2013, Porcelain, 4.5 x 2.4 inches / 11.5 x 6 cm. Photo by Donna Winkler.

Taking all these disparate factors into consideration and adding the globalization of ceramics into the mix, BC ceramics is, at this time, difficult to categorize. In addition, there has been increasing cross-fertilization between contemporary art practices, as barriers crumble and art practices expand their perception of material use. Perhaps by virtue of being corralled within the geographical “isolation” of mountains and sea, and by having commenced a practice free of traditional restrictions, the ceramics made in BC will, over time, speak for this region through the spirit of their variable and unconstrained nature. Future historians may be able to discern influences carried forward from other contemporary art practices, the environmental impact, international heritages, the Leach/Mingei principles and indigenous First Nation’s totemic and form-line traditions. The works featured in this article demonstrate vitality, individualism and breadth – characteristics of the province of British Columbia – and represent only some of the dynamic artists working in the province of British Columbia.

This article is based on Debra’s presentation at the 9th International Symposium Ceramics and Glass between Tradition and Contemporaneity that accompanied the first Cluj International Ceramics Biennale Exhibition in October-November 2013, in Cluj-Napoca, Transylvania, Romania.

Self-taught from 1973-79, Debra Sloan attended the Vancouver School of Art 1979-1982 and Emily Carr University of Art (BFA, in 2004). She is on the North-West Ceramics Foundation (NWCF) board and a co-founder of archival website arch-bc.org. Her work is represented in 6 Lark Publications. Debra was awarded the Circle Craft Scholarship and a BC Arts Council Visual Arts Award for a residency at the International Ceramic Studio, Hungary in 2010, and returned in 2013. In 2014 Debra was Artist in Residence, as the first sculptor at the Leach Pottery in St Ives, since it’s founding in 1920, supported by a bursary from FUSION, Ontario Clay and Glass Association. Debra will have a solo exhibition ‘Horsing Around’ at the Gallery of BC Ceramics – of the Potters Guild of BC and will be represented at SOFA by the Maria Elena Kravetz Gallery in November.

Visit Debra Sloan’s website.

Publications about BC Ceramics and Material Arts

2012 – Back to the Land – 1970-1985, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Diane Carr, Nancy Janovicek

2011 – Thrown, British Columbia’s Apprentices of Bernard Leach and their Contemporaries, Edited by Scott Watson and Naomi Sawada, 978-0-88865-803-6, Helen and Morris BELKIN Gallery

2009 – Fired Up, Contemporary Works in Clay, 978-0-9811862-0-7, Cathi Jefferson, Meira Mathison

2009 – Seeking the Nuance, Glenn Lewis, Potters Guild of British Columbia, 098-0-9696077-1-7, Project editor Phyllis Schwartz, Editor Debra Sloan

2009 – The Art of the Future, 14 Essays on Ceramics, Paul Mathieu

2002-2007 – Craft, Perception and Practice, Vls I, II, III, Rondale Press, Artichoke Publishing, 0-921870-94-9, 1-55380-026-5, 978-1-55380052-1, Edited by Paula Gustafson and Amy Gogarty for Vol. 111

2007 – Transitions of a Still Life, Ceramic Work by Tam Irving, Carol E Mayer, 978-1-895636-82-6, Burnaby Art Gallery

2005 – Source Book, 1955–2005 (disc) Potters Guild of British Columbia, Al Sayer, Debra Sloan

2005 – TransFormations, Burnaby Art Gallery, 0-9738251-0-3, Carol E. Mayer

2004 – A Modern Life, Art and Design in British Columbia, Vancouver Art Gallery and Arsenol Pulp Press, 15515217177, Alan C. Elder and Ian M. Thom

2004 – Hot Clay, Sixteen West Coast Ceramic Artists, Surrey Art Gallery, 0-920181-60-0, Liane Davison

2003 – Sex Pots, Eroticism in Ceramics, Paul Mathieu, A&C Black Ltd, UK. 07136-5804-5

1988 – Made of Clay, Ceramics of British Columbia, Potters Guild of British Columbia, Douglas McIntyre, 1-55054-655-4, Compiled by Linda Doherty

2015. Article published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 3.

Comments 1