Part I. Review of Debra Sloan: Les Grandes Dames

Part II. Interview with Debra Sloan

By Amy Gogarty

Vancouver artist Debra Sloan is best known for her ceramic sculptures of animals and infants, which exude personality and often humour. Her babies, in particular, bely uncritical sentimentality in their frank displays of frustration, anger, and resistance. With her latest exhibition at the Craft Council of British Columbia, Les Grandes Dames, Sloan shifts her attention to the mature female figure, filling the gallery with a full court of alert, expressive beings.

Sloan is a student of ceramic history, not only of British Columbia, about which she writes frequently, but also of the British Leach tradition, European maiolica, Central and South American ceramic sculpture, and Chinese Tang Dynasty tomb figures. These latter works, most notably, those of women and horses, are the inspiration for her current series. During the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE), upper-class women enjoyed a great deal of personal freedom, dressing in elaborate fashions, sporting eccentric hairstyles, and engaging in equestrian activities including playing polo. Their appearance and lifestyle were captured in figures produced in large numbers and preserved in tombs. Molded from white earthenware and individualized through subtle detailing, many were glazed with drips of green, ochre, brown, and occasionally cobalt lead glazes in a style known as sancai. While dancers and musicians were typically slender, courtesans were characterized by mature, robust figures with rounded cheeks and plump limbs. Most of Sloan’s sculptures take their cue from this model of female figure.

Sloan is attracted to these figures for their individualization, unusual at a time when women were rarely accorded much autonomy, and their plumpness. While corpulence was admired at that time, today, body-shaming and the lucrative weight-loss industry militate against representing “real women” with plus-sized bodies. However, Sloan’s portly “grandes dames” are invested with the same seductiveness and charm that characterize the Tang figures.

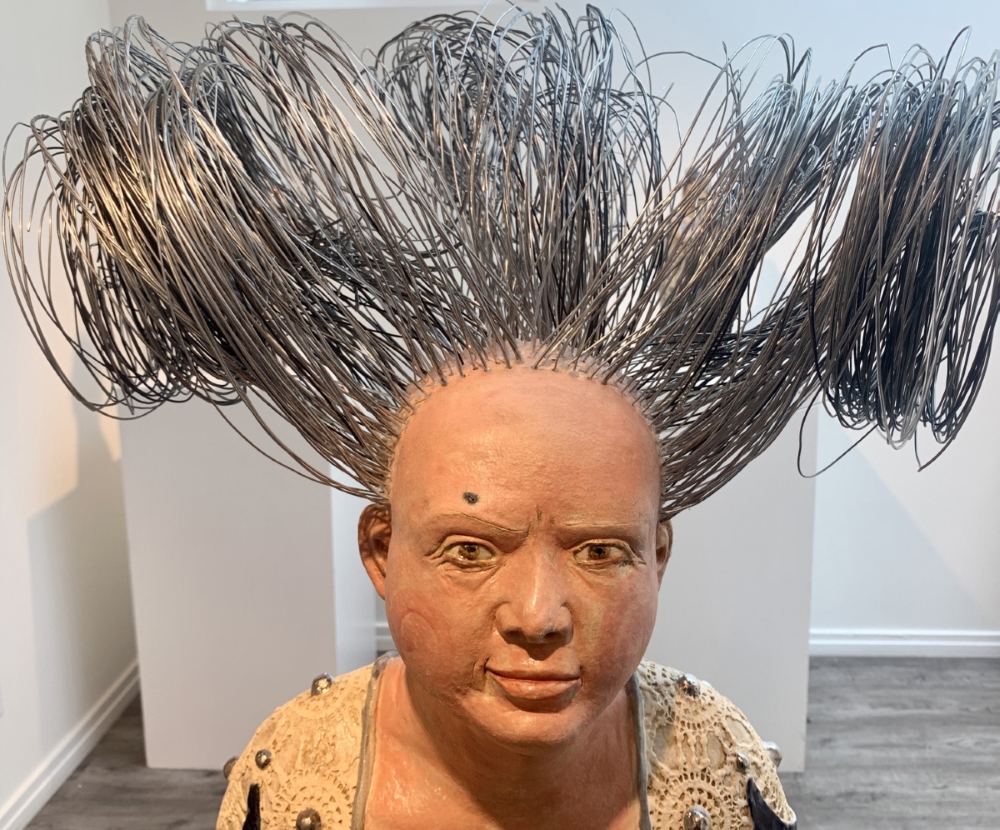

The figures wear long, close-fitting dresses, which reveal their bodies and postures. Hips, buttocks, and bellies jut out in comfortable curves, suggesting pregnancy, and heads tilt up to meet viewers’ eyes. Beginning as thrown or slab cylinders, their relationship to ceramic pots is apparent in their scale. Most are between 16 and 20 inches (40 – 50 cm) tall, rendering them larger than figurines yet still intimate. Their volumetric or “pneumatic” quality results from the artist pushing out from the inside as much as modelling on the outside of the form. Attention has been devoted to the costumes, which include tiny sprigs, colourful drips, flowery stripes, and small nails. Hairstyles mimic the elaborate twists of their Tang sisters, or they comprise curly masses of wire inserted directly into their heads. Yellow Zoom is crowned with streaking bolts of soldering wire, lending her the surprising appearance of a Sci-fi queen, while nails penetrate the scalp of Spikes, creating a distinctly menacing air.

The expressiveness of the figures is conveyed through gestures and facial expressions ranging from wistful to defiant to delighted. Additional attributes are suggested by objects held by the figures. Dress for Pup depicts an introspective woman wearing an elegant gown of alternating pink, blue, and green flowered bands, which clings tightly to her figure. She tenderly cradles a small puppy, who looks out brightly. Plain Jane with Petticoat is slender, her arms held close to her body draped in a filmy pink shift. As she looks up, her wistful expression captures the hopes, dreams, and insecurities of a young girl approaching puberty. A sombre Madonna holds an infant in Tender Hooks. Her hair springs out to form “hooks,” emblematic of the fear, anxiety, and exhaustion that attend even welcomed motherhood.

Intimations of pregnancy and motherhood create a context for including an over-life-sized sculpture of a female baby, which sprawls uncomfortably on a low plinth, her face contorted in an angry frown. Society’s expectation that they become mothers severely constrains the horizons of many women. However desired, the physical and emotional demands of parenting shape opportunities and social perceptions of women’s value. The scale of the baby overwhelms the adult figures, reflecting the worries, responsibilities, and labour that accompany childbearing.

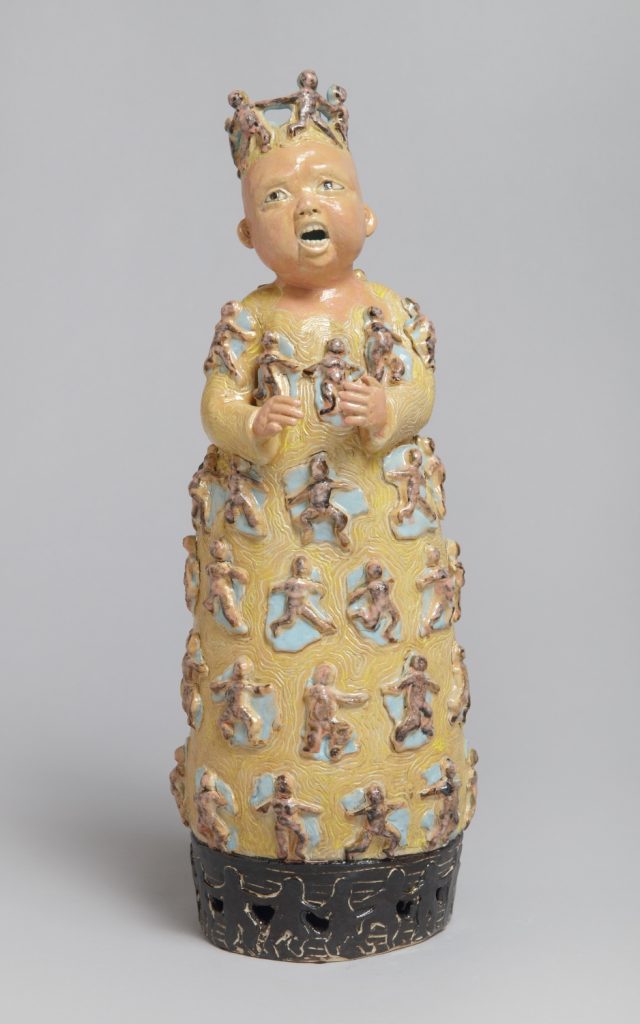

Most figures are grounded by a plinth or floor, which often has its own iconic meaning. For example, Blue Bird Drip perches on a black-and-white checkerboard reminiscent of marble floors found in elite buildings, or linoleum squares popular in suburban homes. Edgy Hair, on Wall stands, arms akimbo, on a platform of red brick. Singing to the Choir, an open-mouthed figure whose dress and crown are decked with sprigs of playful children, stands on an elaborate base that resembles a cake stand, while Spikes levitates on points that form the hem of her dress.

Sloan invests significantly in her surface treatments, which are painterly and supportive of her forms. Coloured slips are brushed on and wiped back to imitate fabric, and given a slight sheen. Faces are carefully delineated, and eyes brightly glazed. Colours are subtle and naturalistic, except for Yellow Zoom, which pulses with shocking yellow energy, and Edgy Hair, on Wall, which is rubbed with a thin cobalt wash to accentuate the surface texture.

Two equestrian figures based closely on Tang examples are included. In both, the horses nearly steal the show with their expressive faces and lively demeanor. In My Horse, a plump, pink nude sits astride her mount, her colourful wire hair streaming behind her. Not Tiptoeing Through Tulips is more complex. The dappled horse stands on a bed of nails as a carefully coifed and demurely dressed young woman leans forward solicitously. The horse’s tail and mane are formed from stiff wire, recalling the Tang horses whose bodies were pierced to receive real horse hair tails and manes, now vanished. The equestrian sculptures reprise a theme of animal sculpture that runs throughout Sloan’s work, most notably in the equestrian ridge tiles that were popular in Medieval Europe and later revived by Bernard Leach.

One very large work dominates the show. The Big Skirt—A Museum was created collaboratively with multi-media artist Drew Shaffer. Standing nearly five-feet (150 cm) tall, the work depicts a woman in a deep blue dress. Her multi-tiered skirt is patterned with decorative corbels, chunky lace, and silver-lustred bosses. Two tiers are bordered with narrow shelves on which sit numerous remnants from Sloan’s long career in ceramics. The shelves contain pieces of Herend porcelain from a residency in Hungary, assorted fragments of friezes and figures, samples of glazes, shards with inlay, and other mementos of a life spent making. The large figure resembles a Renaissance “Madonna of Mercy” who gathers the faithful within the protective shelter of her cloak. Her arms are folded tightly against her body, and her face shows stoic determination and resolve. Most amazingly, her hair, formed from yards of stiff wire, curls up above her head in dramatic horns.

The Big Skirt sums up a number of themes that run through this exhibition: the lived experience of women, the role of ceramics as memory and archive, the resonance of materials, and the pleasures of making. As an unconventional museum, The Big Skirt gathers up and celebrates Sloan’s own life as a maker—and, by extension, other female creators–setting them among the greater constellation of “grandes dames.” Her exhibition revels in the appeal of figural ceramics, celebrating the individuality of women, the complexity of their lives, and the enduring importance of ceramics, history, and craft.

Read Part II. Interview with Debra Sloan

Amy Gogarty is an independent researcher, writer, and artist living on the unceded shared traditional territories of the Coast Salish Peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. She studied at ACA (now AUArts) and the University of Calgary, receiving her MFA in Painting in 1989. She taught histories and theories of visual arts at ACAD in Calgary for sixteen years prior to relocating to Vancouver in 2006. She has exhibited her paintings and ceramics locally and nationally and is the author of over 120 critical essays, reviews, or presentations relating to visual art and craft practice. In 2021, she was named an Honorary Member of NCECA and short-listed for the Canadian Crafts Federation Robert Jekyll Award for Leadership in Craft. She sits on the Board of the North-West Ceramics Foundation and is a passionate supporter of ceramics in British Columbia.* (*Source: Craft Council of British Columbia’s website)

Debra Sloan: Les Grandes Dames is on view at the Craft Council of British Columbia, Vancouver, between June 6 and July 25, 2024.

Visit Debra Sloan’s website.

Ceramics Now is a reader-supported publication, and memberships enable us to produce high-quality content like this article. Become a member today and help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Studio photos by Ted Clarke. Installation views by Debra Sloan.