By Sanne Flyvbjerg

Beginnings

It begins with a black-and-white photograph from the 1950s. Danish artist Axel Salto is standing in the old coal kiln in The Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Manufactory in Copenhagen, looking down at one of his masterpieces, The Core of Power. It is a sculpture, an object, an almost living thing made out of clay. Despite being fired into ceramics, its clay body appears to be growing on the spot. Something sprouts from the budding base, placed on the kiln’s floor next to Salto’s shiny shoes. He looks down at this wilful object with its three compelling but disturbing limbs, and it seems to look back at him as if it had something to say about its own nature and origin as if it were alive with the very fire that hardened it.

This picture of Axel Salto shows the conversation between an artist and his work. But it is also an apt portrait of a man who was always in urgent conversation with the world around him, with the sea shells that he found on the beach, with cones, fossils, clay, paint, pen, and paper, or with all the people he collaborated with. Axel Salto was always working, thinking, and writing, always exploring the beauty and danger of what he called ‘the miracle of growth,’ the never-ending sprouting force that constantly makes and breaks the forms and bodies of nature. Throughout his life, he was inspired by images of growth and transformation and, in fact, sought to embed the very experience of our pulsating world in his work. Sprouting plant motifs, bulging ceramic objects, glazes in flux, and repetitive designs in patterns of vibrant colors and dynamic motifs are examples of this across media.

Words and clay

The black and white photograph marks the entrance to the exhibition Playing with Fire: Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto, which is currently on show at CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark. But, as the title suggests, it also marks the beginning of a conversation across time between Edmund de Waal, porcelain’s storyteller par excellence, and the 20th-century Danish master of stoneware. It is a conversation that takes us to the heart of Axel Salto’s practice but also to a significant artistic encounter. At first glance, there seems to be a long way to go from the drama of Salto’s sprouting works in burning, smoldering glazes to de Waal’s installations of small porcelain vessels with subtle variations in glaze color. But if we look beyond the surface, the stylistic differences between these two artists are canceled out by the similarity in working methods, their understanding of creativity, and their expression in both words and clay. Both are writers who reflect on the meaning and emotional value of objects and materiality through writing. As a result, we find the written voices of both artists as a conversation that runs throughout the exhibition. Words, clay, and materiality are deeply connected.

Going for a walk

‘This is a very personal walk in the company of Axel Salto’. These are the first words of Edmund de Waal’s narrative that runs along the walls of the exhibition. When he was asked to curate an international exhibition of Salto’s work, going for a walk together was his way of approaching the encounter with the complexity of Salto’s endless repetitions and variations of form. De Waal was driven by the urge not only to understand the work but also to get to know the person behind it. To understand Salto’s ‘pacing of the world’, to see what he saw when he walked along the pebbled coast in Denmark or up the mountainsides when he lived in the south of France. ‘Imagine walking with him in the country. He notices things, turns back, picks up stones, draws a leaf, hums a tune, tells a story, meanders, pinches some clay into a little vessel’, de Waal’s text continues.

As a result of this imaginary journey with Axel Salto at his side, de Waal has designed the exhibition as a walk through different spaces that convey the pulses of energy that run through Salto’s practice. It is a winding road through a display of his expressive work in various media – his ceramics, prints, sketches and drawings, textile and paper designs – and his words and books.

The exhibition is the culmination of a conversation that began 30 years ago when Edmund de Waal first saw Axel Salto’s budding and sprouting ceramics at the Danish Design Museum in Copenhagen and left the building quite confused and mystified. Years later, in his book ‘20th Century Ceramics’, he placed Axel Salto among a group of post-war existentialists who were dealing with the anxieties of the nuclear age. But as de Waal discovered in his research for this project, Axel Salto is not only concerned with the potential hazards of the nuclear era and the awe-inspiring force of nature. Salto’s work is also driven by pleasure, playfulness, and an unquenchable thirst for knowledge that draws him closer to the core of nature, art, and existence.

Into the burning now

The drama in Axel Salto’s practice revolves around his obsession with the constant metamorphic movements in nature and the seductive and dangerous potential of change. In his book ‘Det brændende Nu’ (1938), Salto introduces the term ‘the burning now’ to describe the very moment when one thing becomes another, be it the instant a germinating bulb first breaks open or the moment when the antlers penetrate Actaeon’s forehead as he transforms into a stag. Such beautiful and inexorable moments of metamorphosis are essential to Salto’s art, and the search for them seems to guide his hand as he lengthens the spikes on his vessels right to the point of breaking.

Creativity is an ongoing process in which making and breaking are inextricably linked, something that unites these two artists on a very deep level. ‘If one thing really works, I don’t care how many things go wrong’, Edmund de Waal said as he opened his kiln to find only one beautiful porcelain tile among several broken ones. Shards are also part of his walk with Salto. It is part of the conversation about change. When you open the door to the kiln, you never know what you will find. Playing with fire is what potters do. At some point, you have to surrender to the unpredictability and caprices of fire. A kiln is a place where you have to slow down and let go.

Moving from the kiln

And this is where Edmund de Waal’s walk with Axel Salto begins. The first space of the exhibition is a dark kiln, a black installation filled with Salto’s masterpieces on open display. Once our eyes have adjusted, the glazes, shapes, and colors come to life in the congested, shadowy space of the kiln. This is where de Waal has the opportunity to fulfill what he describes as a personal desire to bring things together in close proximity and understand Salto’s work in a physical way. And this physicality is important throughout the exhibition. Wherever possible, Salto’s works are presented in close proximity, not isolated in vitrines far away from each other, but as pulses of juxtaposition, as objects in conversation with each other. They are presented in much the same way as Salto presented his work in the 1950s, in layers that allow us to see how shapes and patterns jump from one medium to another, how his dynamic sketches and drawings correspond with ceramic forms, or how he repeats patterns engraved in ceramics in colorful designs for textiles and paper.

The black and white photograph transforms into a saturated, polyphonic space of color and play. The exhibition offers a transformative journey through different spaces that show Salto’s stoneware up close, his yellow, blue, and red glazes, his colorful book designs, his exploratory drawings, his obsession with metamorphosis and the haunting tales of Ovid, and finally, his advocacy of art, creativity and play in children’s lives. In this last space, everyone is invited to stamp with reproductions of Axel Salto’s printing stamps for children from the 1940’s. Although the furniture is designed for children, you will often see adults sitting at the low table, stamping away, following Salto’s advice to play, try things out, and let the stamps work on their own. ‘You are in the world of printing stamps, in Magic Land, where you can decide everything’, Salto writes, and Edmund de Waal has stuck this wonderful phrase on the wall by the table. An important message to convey today when many children are faced with defined activities and narrated learning.

A porcelain pavillon

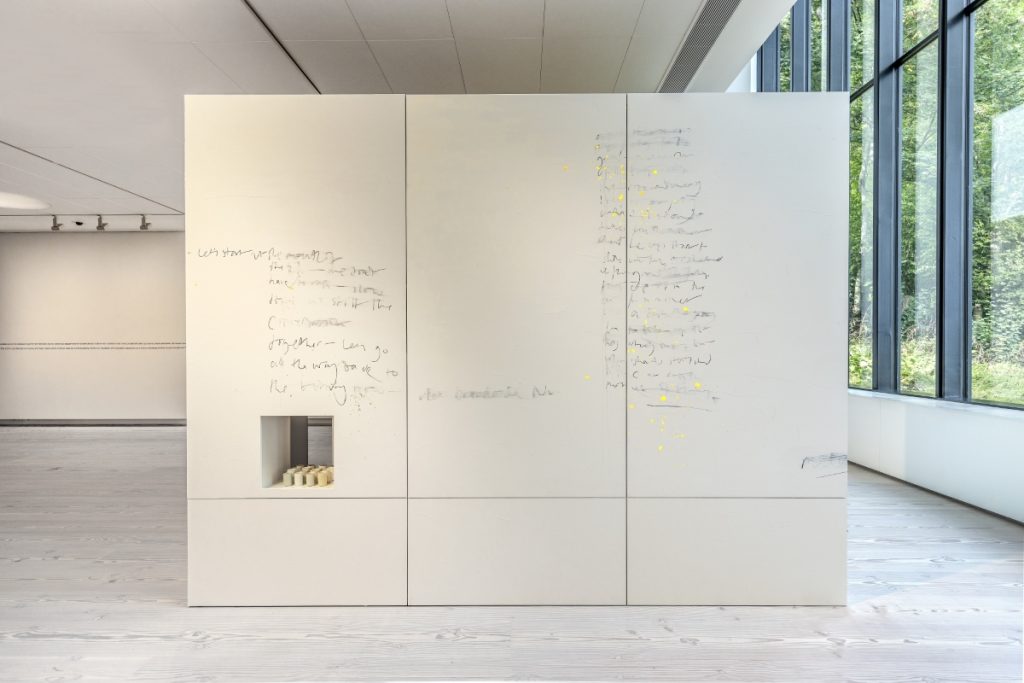

And so, after the winding road through Salto’s life’s work, we encounter Edmund de Waal’s new installation, which he has called ‘the burning now’. The title is, of course, a homage to his interlocutor, but it also refers to the moving feeling he wants to convey with his installation. In contrast to the dark and theatrical kiln room at the beginning of the exhibition, de Waal’s ‘burning now’ is a white pavilion covered in porcelain slip with gold and words about metamorphosis embedded in the kaolin. Inside the pavilion, soft light falls through a skylight made of thin porcelain tiles, gently illuminating a large vitrine containing a poetic response to Salto made of beaten silver, porcelain tiles, shadows and voids. Every object in the installation has gone through stages of transition, whether it is porcelain vessels, shards, or oxidized silver. The installation is an articulation of de Waal’s journey with Salto and a kind of shared space that speaks of anxiety and play and the absolute necessity of making texts and objects and placing them near each other. And to keep going. ‘To return to the things that matter. To repeat and believe that it’s possible to start over, to make another vessel and to do more with the material between your hands’, explains de Waal.

And so the exhibition begins and ends with clay. With Edmund de Waal continuing the experiments that Axel Salto can no longer carry out, challenging the material, failing and succeeding in shaping very thin porcelain tiles for the first time. De Waal’s installation is a quiet room, and yet ’you just want it to sing,’ he explains. And Salto seems to be responding from the past, bringing his own vessels into the soundscape: ‘In these smoldering, gushing vases, the stoneware bursts into song, and for what else, actually, should clay be used? For play when the heart swells, and for relief from misery.’

Art can be craft can be art

A walk with these two artists is also a walk away from old and restrictive distinctions between arts and crafts. Edmund de Waal is a pioneer in bringing pottery into the world of fine arts. To complete the circle, Axel Salto insisted that art should be a part of interior design, alongside beautiful furniture or perhaps curtains made of his own textile design. In the company of these two artists, the separation of arts and crafts does not seem to make sense. ‘It’s a grotesque simplification of the power and presence of objects. A misunderstanding of what work means’, says Edmund de Waal, and Salto replies: ‘Thus the work of art, the eternal thing, has its message to convey from person to person. Like a radiator, it should be introduced into modern homes, then you could really talk about functionalism.’

The walk is coming to an end. But the conversation continues. There is more to say. About the collective efforts in art. About how crossing boundaries can serve as interesting bridges toward new conversations and collaborations. Salto crossed many disciplines throughout his life and collaborated extensively with fellow artists, glaze engineers, potters, architects, editors, bookbinders, printers, and other specialists. He said that his stoneware would never have seen the light of day had it not been for his collaboration with the ceramicist Carl Halier. Although he believed that the artist had a special voice and responsibility, he was well aware that he owed much of his success to a team of skilled professionals. Or as Edmund de Waal puts it when talking about his studio of artists, creatives, and specialists: ‘There is absolutely the existential moment of making a pot or a text by yourself, but then there is the whole collective endeavor that allows it all to happen.’ A skilled man in each station, as Axel Salto puts it in 1949 when he talks about doing the works for his 60th-anniversary show at Charlottenborg in Copenhagen. ‘All the ceramic objects in the exhibition are the result of collaboration at The Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Manufactory, teamwork. The most skilled man at each station – turner, glazer, kiln-man, artist, otherwise we would never have come very far … Should you offer me acclaim, I point to my comrades and invite them to share it with me. We line up and bow. Curtain down.’

The exhibition Playing with Fire: Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto is on display at CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark until 11th August 2024. After that, it will travel to Kunstsilo in Norway, and its final showing will be at The Hepworth Wakefield in England in 2025. The exhibition is a conversation across time that continues in the richly illustrated book Playing with Fire, that has been published together with the exhibition by Forlaget Press. The book comprises a rich selection of excerpts from Axel Salto’s writings that have been translated into English for the first time, a new essay by Edmund de Waal in which he investigates the concept of metamorphosis and the fusing of clay and words, an essay by co-curator and writer Sanne Flyvbjerg as well as her conversation with Edmund de Waal in which they explore Salto’s practice and the artistic encounter.

Playing with Fire: Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto is a result of a collaboration between CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark and Kunstsilo in Kristiansand, Norway. The exhibition presents works from the collections of both institutions: The Royal Copenhagen Collection at CLAY and the Tangen Collection from Kunstsilo. The works are installed in an exhibition design by Hutchison Kivotos Architects in London. A generous grant from the British philanthropic AKO Foundation supports the exhibition project and its international tour.

Axel Salto (1889-1961)

Axel Salto was a prolific artist, designer and writer, who played an important role in Danish Modernism. Over the course of five decades his practice expanded from painting to include ceramic, woodcuts, graphic design, book illustration, jewellery, textile design and interior design. In 1914, he graduated as painter from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In 1917-20 he founded the avant-garde journal Klingen (The Blade). His career as a ceramicist began in the 1920s when he designed porcelain vases and bowls for the Danish manufacturer Bing & Grøndahl. From 1929 he was linked to the stoneware studio at The Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Manufactory. His partnership with Royal Copenhagen continued for more than a decade resulting in new iconic sculptures such as ‘The Atomic Bomb’ (1949) and ‘The Core of Power’ (1956).

Salto designed wallpaper and paper for bookbinding throughout the 1930s and 1940s. From 1945 onwards he collaborated with the Copenhagen firm L. F. Foght, for which he designed patterns for printed fabrics. Alongside his artistic work, Salto published a number of books of his own design. He also wrote countless essays, columns and articles. A highly influential retrospective work, The Sprouting Style (1949), was published in honour of his 60th birthday.

Salto had numerous solo-exhibitions in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and France. He was awarded the ‘Grand Prix’ at the World Expo in Paris in 1937 and at the Milan Triennale in 1951. In 1961 he received a gold medal at the international ceramics. exhibition at Musée des Beaux-Arts In Ostend, Belgium. In the 50’s his ceramics and textiles played an important role in promoting Danish design and crafts, known as Danish Modern, in North America.

Edmund de Waal (1964-)

Edmund de Waal is an internationally acclaimed artist and writer, best known for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, often created in response to collections and archives or the history of a particular place. His interventions have been made for diverse spaces and museums worldwide, including the Musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris; The British Museum, London; The Frick Collection, New York; Canton Scuola Synagogue, Venice; Schindler House, Los Angeles; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna and V&A Museum, London. De Waal is also renowned for his bestselling family memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010), and The White Road (2015). His most recent book, Letters to Camondo, a series of haunting letters written during lockdown was published in April 2021. He was awarded the Windham-Campbell Prize for non-fiction by Yale University in 2015. In 2021 he was awarded a CBE for his services to art.

Sanne Flyvbjerg is a curator and writer.

Captions

- Playing with Fire – Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto, installation view, colour, CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhøj

- Playing with Fire – Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto, installation view, line, CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhøj

- Playing with Fire – Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto, installation view, colour, CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhø

- Playing with Fire – Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto, installation view, play, CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhøj

- Installation view. Collection of Salto’s ceramics in ‘the kiln’. CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhøj

- Installation view. Collection of Salto’s ceramics in ‘the kiln’. CLAY, 2023 © Axel Salto – VISDA Photo Ole Akhøj

- the burning now, installation view, CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art, Denmark, 2023 © Edmund de Waal, Photo Ole Akhøj

- the burning now, installation view, CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art, Denmark, 2023 © Edmund de Waal, Photo Ole Akhøj

- the burning now, installation view, CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art, Denmark, 2023 © Edmund de Waal, Photo Ole Akhøj

- the burning now, installation view, CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art, Denmark, 2023 © Edmund de Waal, Photo Ole Akhøj