By Doug Navarra

The first thing I thought about when I first saw works by Jennifer McCandless were active notions of persona and personality. What makes her exhibition Run Amok at A.I.R. Gallery different is this very fact—the show is concept-based—and not center-staged upon materiality. This exhibition is composed primarily of figural works, and if they are not straight-out renderings of the human/figural body, then they are creatures and monsters that have sprung from the underworld. These are statements to define personality and persona and to make statements about what that means from a woman’s perspective.

In a post-funk and with a post-Arneson mannerism, McCandless’s ceramic and mixed media renderings signal the truths that can be distinguished through the imagination, depicting these magical figurations of both substance and innuendo.

Persona is a concept tastefully conceived through a reflection of inner individuality and an outward sense of self. Persona is a stratagem of identity in public, in this case, a ceramic sculpture that adopts a feminine perspective for a social statement, which at first may appear to be a fictional character. Yet there is always the inner world of deep personal feeling present.

As ceramic parodies, these constructions lampoon our quotidian patterns and expectations, but they also can become caricatures of a dark, unconscious side while performing on a very conscious but satirical platform.

Persona is at the heart of her character development. But in order to develop persona, McCandless shows us that she is thinking extensively about each character that she portrays. Who are they? Where do they come from? What do they want? What do they think about? What are their fears and ambitions? Personae, as a collective, is built around these conditions, yet persona, individually expressed, also comes with a “back story” for each construction.

Together, these works offer/suggest a social critique of our collective being but also question how we individually relate to one another and interpret the world at large.

These are works that champion creative freedom and reflect the artists’ personality and experiences. Imbued in them are a sense of humor, a confrontation to autobiographical references identifying on a personal level the social, political, and existential references that may convey a more serious undertone. Whimsical contents can mask a darker or, perhaps better yet, a more critical subject or element, eroding the distinction between the figure’s exterior and interior meaning.

It was, in fact, Carl Jung who first developed the notion of persona and, as such, was engaged in the task of discovering and constructing the archetypal architecture underlying human experience. McCandless invokes this Jungian notion as it means seeing through the connective, rather impersonal structure and dynamics of the unconscious. As Jung says, “The persona is a complicated system of relations between the individual consciousness and society, fittingly enough a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and, on the other, to conceal the true nature of the individual.“1

For McCandless, this is what creates her “magical realism” as both raw material and the finished product of her imagination. This is to see how fantasy is creating reality, how reality is creating fantasy. These compositions are the metaphor of an “as-if” fiction; both are a form of being. From an internal animus to ‘anima mundai’, these works depict a back-and-forth shift from her personal mirror to an open window of the world.

Given the demands of everyday life, the obligations to family and friends, the chores, errands and logistics, and social parameters we must deal with, the idea of lending ourselves “spare time” to gaze into the make-believe world of McCandless may seem a bit jocular irreverent. But as renderings of fictional characters who poke fun at social norms, these works invite their audience to explore real ideas, issues, or possibilities using an otherwise imaginary setting, perhaps something similar to reality but totally distinct from it.

Even though we are gazing into a world of what she calls “magical realism”, we can, as spectators, see her expressions of the trials and tribulations of daily life, the accompanying vicissitudes of hope and fears, and nuances of social dynamics rendered in these characters. This allows the viewers to experience life through a different narrative and thus see the world through a different lens. These offerings are valuable insights into how she sees the sometimes inordinate, dizzying, and immeasurable world we live in. What unfolds in these characters of hers is an expression of the social personalities of present-day Funk.

INTERVIEW

On the Thursday before the opening of her exhibition, Jennifer McCandless and I met at AIR Gallery in the DUMBO neighborhood of Brooklyn. We decided then to construct a question-and-answer exchange, speaking more specifically about some of the works.

First I want to say “Congratulations!” on the show. I always think it’s important to acknowledge a solo exhibition as a milestone in the career of an artist.

Thank you! I am delighted to be installed here in the A.I.R. Gallery. It happens to be the oldest feminist gallery in the country and honors the specific vision of the female artist. My gallery space here is compact, with many works from the last few years. It’s actually similar to my studio space in Burlington, VT., a total menagerie of ideas.

Right! I’m hoping this exchange will give us an opportunity to understand the specific nature of your work and the influences and motivations behind it. This work, ‘Western God Trying to Convince Other Gods They Never Existed,’ seems to me to be a very important work in the show. Could you tell me a little more about what’s going on in this piece?

This will actually be really fun to explain; however, I probably should mention a little bit about the context of my personal background. I was raised by two ex-Catholic parents who enjoyed questioning everything. However, at times, my parents also possessed a very dark sense of humor. It seemed to not make sense to me as a small girl that there was a God who looked like us somewhere up in the clouds, along with the collaborating premise that men were made first and women sprang from them. I saw that women were blamed for the expulsion from the garden and consequently were to be tamed and made to submit. At the forefront of this work, I’ve placed the “Western God”, which in my mind is depicted as the real God. The other surrounding gods he is lecturing to are from all sorts of places and time periods, many much older than the “professorial” Western God. Depicted here are Bes (Egyptian God of childbirth, music, and merriment), Monkey King, Sun Wukong (Chinese), and Tlaloc (Aztec God of Rain). They are gathered in a surrounding classroom-like grouping, and they find the argument amusing. So here I am poking fun at that notion, while on a more serious side, this piece is engaging in a statement about equality, where there is no inferiority to each other.

You previously mentioned to me the influence of the Belgian painter James Ensor (1860-1949). He was such a fantastic character in his day. Not one who could be considered an “outsider” artist but so idiosyncratic that it is hard to place him in the mainstream canon of art history. Ensor seems so very pertinent to your work. Can you explain how you came about finding him? Was this what one might call a “eureka moment”, or were you pondering his paintings for a while? How does he connect with you?

My parents loved Symbolism, and so I remember seeing some small traveling pieces by Ensor early on before I became an artist. My Dad, also an artist, would often bring us to the Detroit Institute of the Arts, where, as a child, I first discovered Ensor’s work. They felt so much more human than the other work at the museum, even though they depicted people masked. The use of the paint/line and blurring to describe emotion was riveting; I guess I’ve always felt like I don’t really understand people, and it scares me that people can seem safe but hide their own monsters underneath. I know not everyone is monstrous, but sometimes I have a tough time discerning. I know also that I have grappled with my own monsters, so there’s that too. I’m not above it.

I used to sit with that painting ‘Christ’s Entry into Brussels’ regularly when I was getting my BFA at Otis/Parsons. It’s a gigantic painting, and now it has its own room in the Getty Museum, which it totally deserves! It’s my favorite piece by him, and it changed my life, honestly. The idea that each person has a secret life reality as well as a public face, that we all share something profound that is not often probed. That’s where I like to explore and dwell and find connection to the viewer. This is present in most of my pieces.

I’ve read that Ensor was interested in the notion of masked figures and especially the carnival atmosphere that annually was paraded through his home country of Belgium, which he often was witness to. The masked personae became a way to project his innermost thoughts. Your figural works are projecting real-world feelings as well. In your renderings, would you say you are using some sensibilities of “a mask” (as an underlying psychology), perhaps just in different contexts? I mean, you are speaking about a “secret life” and conveying “a public face.” There is always an inner and an outer.

I would be concerned if people thought the Gods piece were really figures wearing masks. The connection between the Gods piece and Ensor’s works is in the idiosyncratic and endless inventiveness of the human mind. It is also in our search for community and connection. As I see it, this is driven by our fear of death.

Like him, the use of bright, fun colors attracts the viewer, and then one realizes there is a possibility of chaos and darkness underneath. I think there is magic that happens in a work of art when it engages in a “pluralism” of this sort. It is a fetishization of the subject in space. The overwhelming figures in the Ensor piece and the number of gods in my piece create an energy and wonder that draws the viewer in to explore, interpret and think. The bright colors signal safety, yet there is an invitation. Like Ensor, but in my own way, I employ this fetishization in order to create an inherent overwhelming energy. For instance, there are some very intense surface treatments in my work. For both Ensor and myself, it is the human condition that connects our work. It ushers in this mystery of ever truly knowing oneself and the challenge of knowing others in the community.

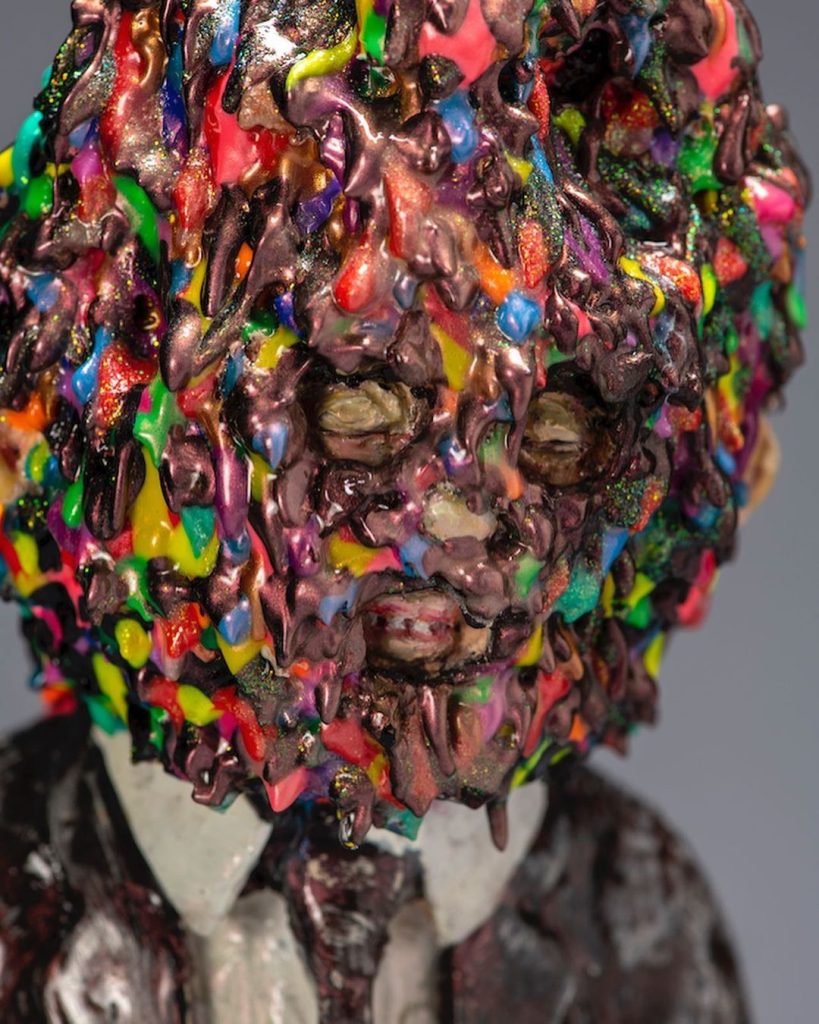

I wanted to ask you first about the work titled ‘Sweat’ and what that piece really means to you.

“Sweat” came to me as a ceramics sculpture teacher during the pandemic. I was watching the vitality of my students slowly retreat, suffering so much loss from the isolation. With my two children, I was also acutely aware of their loss. So, for this piece, I used colors oozing from the head to represent the loss of their childhood vigor. I studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where we were constantly questioned about the marriage of our form, materials, and the way we used them. This was alongside the content of the work. As a matter of consequence, I will introduce elements in my work that are mixed media when they are best suited to match the idea of a piece.

There are also the works of Bob Arneson, who loom large for you in terms of influence. Notably, he often worked with self-portraiture to project his means of identity and his innermost feelings. In those cancer portraits that Arneson did in the last years of his life, there is that “feeling of disintegration,” as you say, where he distorted the physical figural component of the image. Your work ‘Sweat’ appears to morph the human head into a Kafka-esque manner of something other than what the human body really is.

I love the irreverence of Arneson and his total exploitation (in a good way) of what clay can do, for instance, the self-referencing of himself as kiln man, his head splatting upside down, his portrayal of himself as a bad dog who just left a mess on the gallery floor, or his feelings of disintegration in his later work when he had cancer. They are very potent images. Humor, to me, is a pathway into a person’s heart, a way that people can safely go to dark places and maybe bring some levity to the stuff that is hard in life. I like going there and sharing that with people. That experience completes the work for me, …the sharing of it.

What about ‘King Cedric: Eater of Mutton? That’s also a fairly “distorted” comical portrait.

In ‘King Cerdic, Eater of Mutton’ and other works in that series (there are five patriarchs), I use the qualities of the clay, the lumpiness and cracking, to depict the demise of patriarchy. Yes, Arneson sometimes depicted himself as disintegrating. He opened those doors for me, and I walked through them and came out the other end. However, I do have a very different point of view and life experience. For instance, there are pieces in the exhibition that address drug addiction, loss of habitat, body dysmorphia, as well as a reimagining of mythology concerning women. That would be a big difference from Bob Arneson and James Ensor.

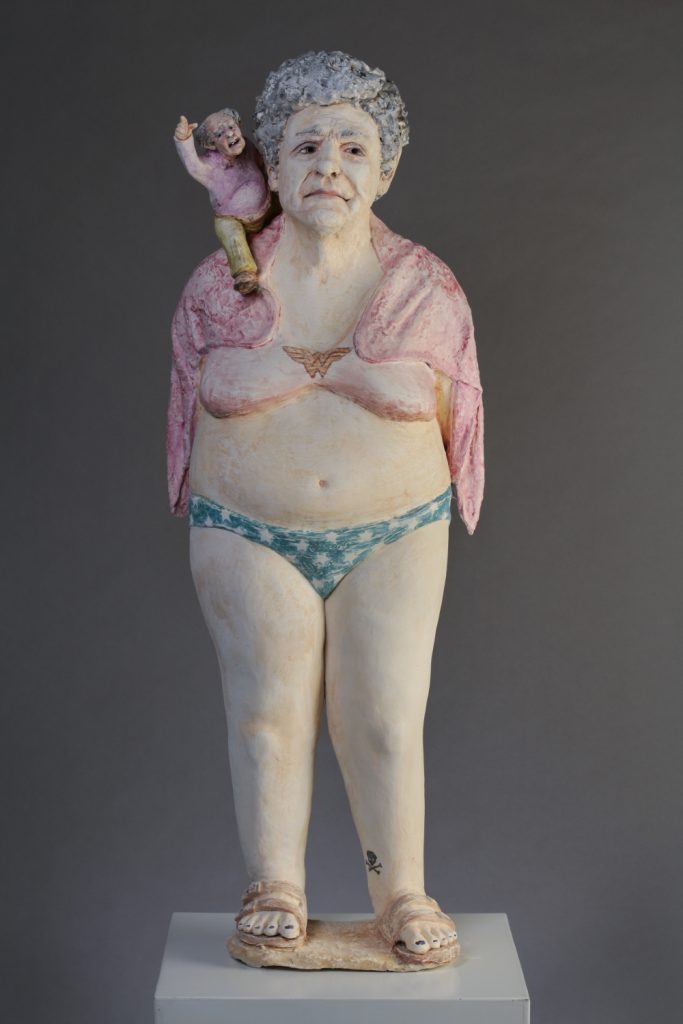

As another dimension to your work and concerns, I’d like you to say a few things about ‘Baby Boomer Bad Ass Pictured with Patriarchal Shoulder Parrot’. That also possesses some very explicit undertones and substantial cultural ramifications.

In the Baby Boomer piece, I am both trying to honor the women who fought on every front for equality, especially in the late 60’s and 70’s. They brought about real change in women’s lives. I feel that indebtedness. It is my good fortune that I have been able to live the life I have, which I owe to them. My mother raised me to fight for my place and not accept being looked upon as inferior. For me, it’s been a lifetime of poking the bear through my art. I hope that’s what comes across in these works: the commonality of experience. Women have not been fully appreciated in art history. What we go through and how we see things allows me to laugh at what otherwise is eternally upsetting. In this regard, my work is a personal coping mechanism. It’s a bonus when this statement reaches into the public domain. This completes the work to make someone laugh and groan at the same time.

Doug Navarra is a visual artist who has an extensive background in working with clay. He lives in Hudson Valley, New York.

Jennifer McCandless: Run Amok is on view at A.I.R. Gallery, New York, between October 14 and November 12, 2023.

Sign up for Ceramics Now Weekly if you’d like to read similar articles on contemporary ceramics.

Comments 1