By Nikhil Purohit

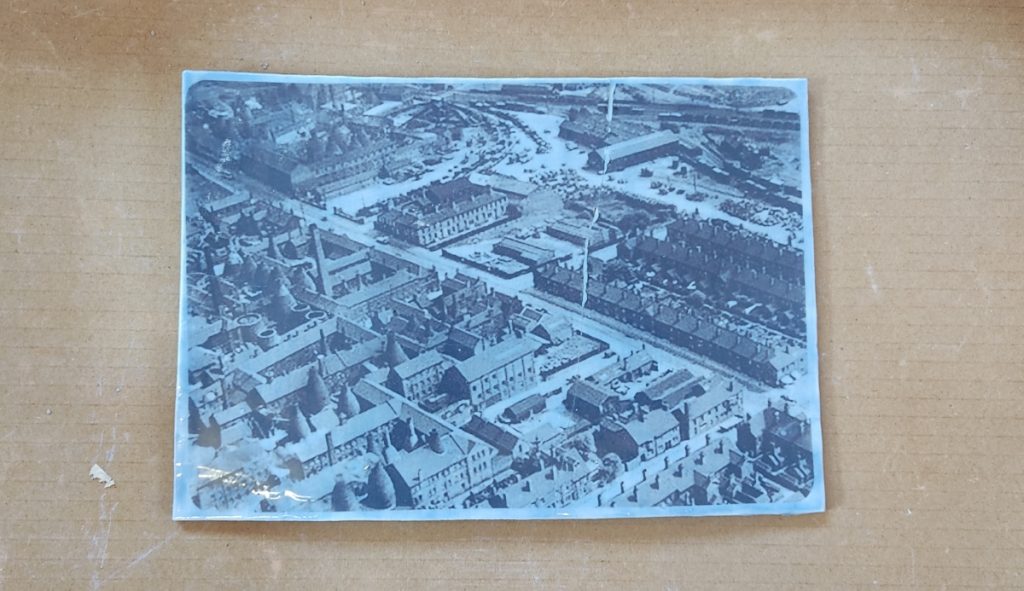

As children, we tend to imagine that the clouds are formed by the smoke belching out of the chimneys of an industrial town. A typical iconic sight of the past centuries. The urban sites are often known by what they produce- both industrially and culturally. Neha Gawand Pullarwar, a ceramicist of repute from Mumbai, India, builds her clay narratives by finding and connecting such anecdotes between the industrious cities of Stoke on Trent and Mumbai as part of the British Ceramics Biennial (BCB) through a residency exchange program between the ICT (Indian Ceramic Triennale) and the BCB supported by the CWIT (Charles Wallace India Trust).

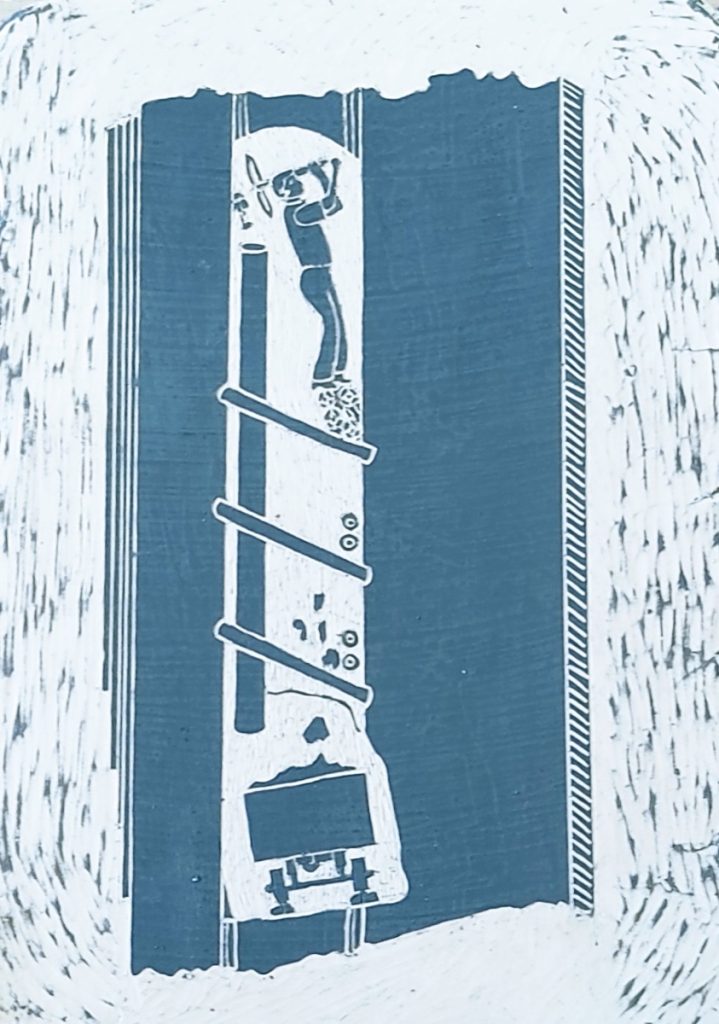

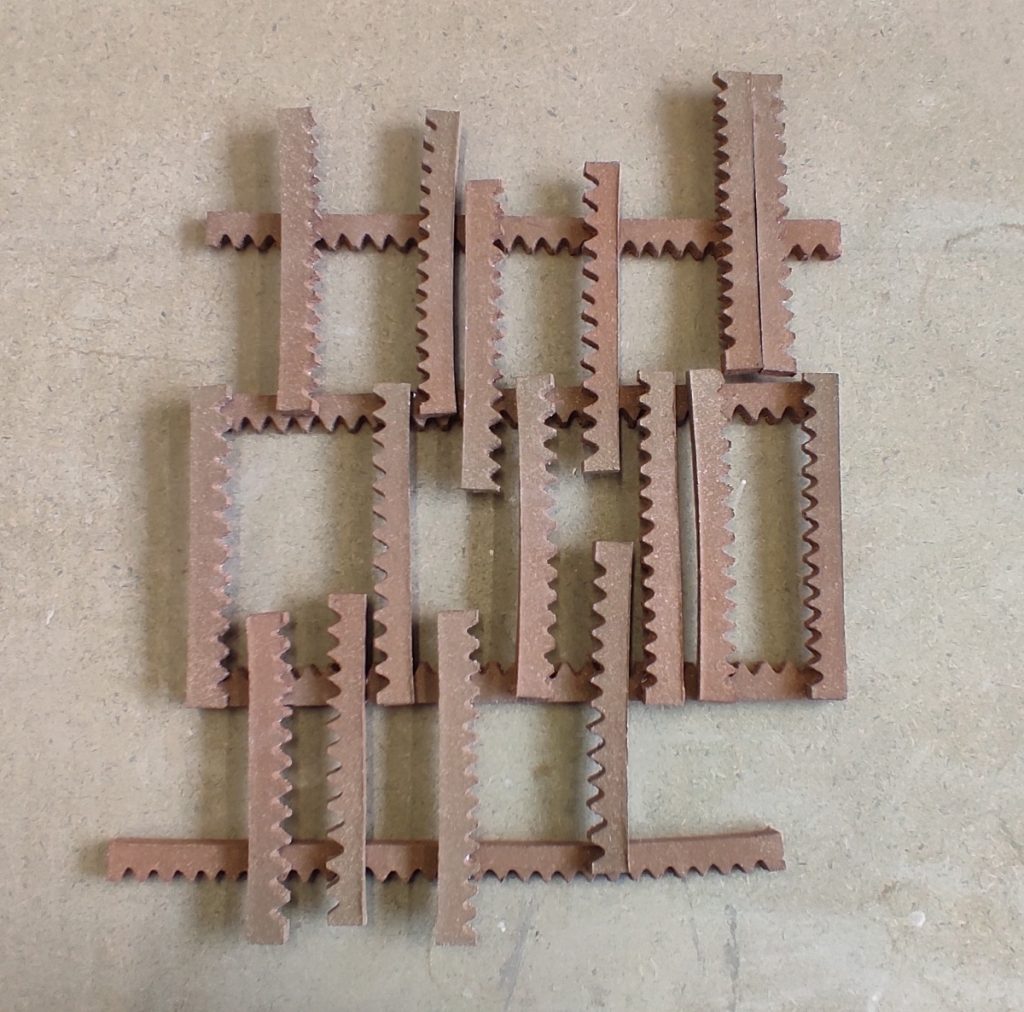

The residency programme was held between 18th August to 29th September 2023. Neha’s proposition was layered with artistic research, where she traced visual commonalities and factual connections between the two cities of industry and the people. In a broader sense, the artist is seen to classify the nuances of Trent’s ceramic histories and the social upheaval around the mill histories of Mumbai. Though each location is independent of their developments, the juxtaposition of the respective visuals and narratives triggers empathy toward the working class and the creative spirit each place ushers throughout their lived past. It becomes even more intriguing when Neha, as a ceramicist, recreates the visuals in clay by image transfer techniques and functional yet sculptural forms of the industry settings to manifest a sort of scaffolded installation hinting at the ongoing industrial operations and the life instances of the working-class heroes.

Neha shares a special relationship with the island city of Mumbai for having lived and witnessed the shifts and socio-political tensions between the working class and the business class. Her connection with colonial history is a major signifier owing to her art education at the Sir J J School of Art, Mumbai, an institution set up during the mid-nineteenth century aided by the leading Parsee merchant Jamshetji Jeejeebhoy. All these references become the point of departure for making her first set of works during the Trent residency, where she uses the Saggars as a frame to contextualize her narrative.

It begins with the choice of making Saggar forms. (Saggars are high-fired groggy forms used as containers, where the glazed pots are kept inside to protect from the dust of the coal that was used as fuel for firing.) Saggars from the Industrial Age have all become collectibles and are seldom found lying around in ceramic factories. It became pertinent to revise her original idea of using available saggars as a wall and produce some by adapting to the eventual outcome. Perhaps this decision informs her work of the shifts that have happened at Stoke-on-Trent, where social and geographical changes like the packhorse road to the proposition of canals in the city to the railways, and finally, the shutdown of factories or shift of designing and manufacturing to China.

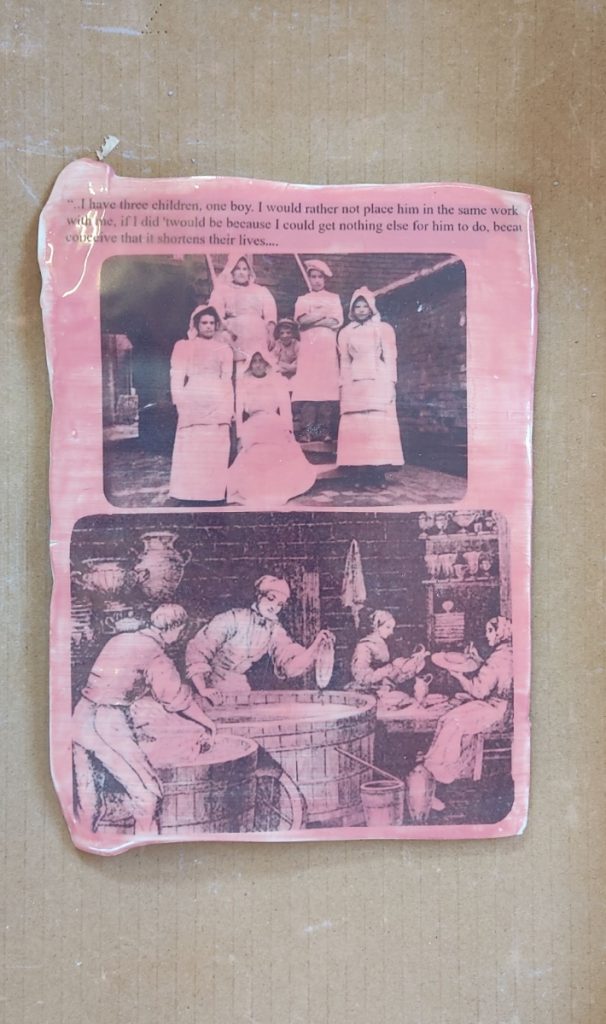

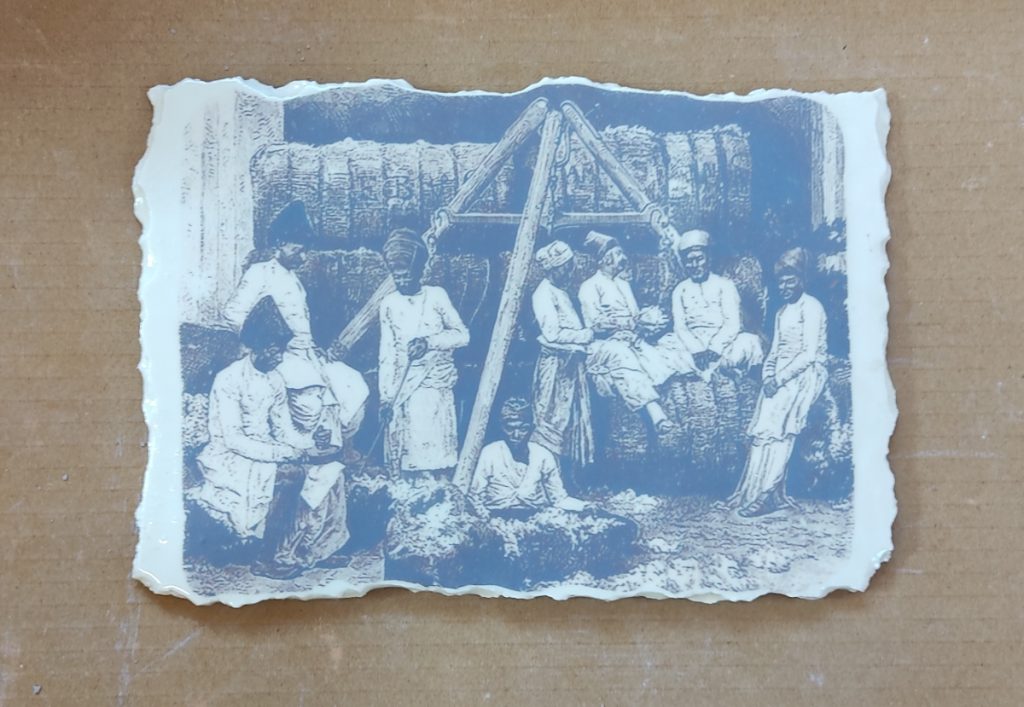

In contrast, the city of Mumbai (Bombay) that changed hands as land given to the British Crown as dowry and eventually the establishment of a major administrative and trading port city and unison of the seven islands into reclamation land underwent innumerable socio-political changes, including the developments in the creative sectors. Neha brings the elements of the labor movement of the 20th century as a marker of a social change symbolized by the red fist, an icon of resistance marked by the nine-month-long Great Bombay Textile Mill strike of 1982. The colored threads indicate the vivid textile trade of the period. Today, the Maharashtra state government is forming a textile museum on the site of Indu Mills- one of the prime sites of protests that even today carries some of the machine remnants from the olden days. The image transfers she uses are of the historic photographs where the merchants from the 19th century are seen resting after the cotton is being weighed, the women at work in a textile unit, the interior views of the ruined mills with machinery in situ, humongous group of workers striking on the streets. Apart from raising questions about the disturbing past of the city and its politics, it ushers a sense of disharmony toward the industrious -creative attitude of the city.

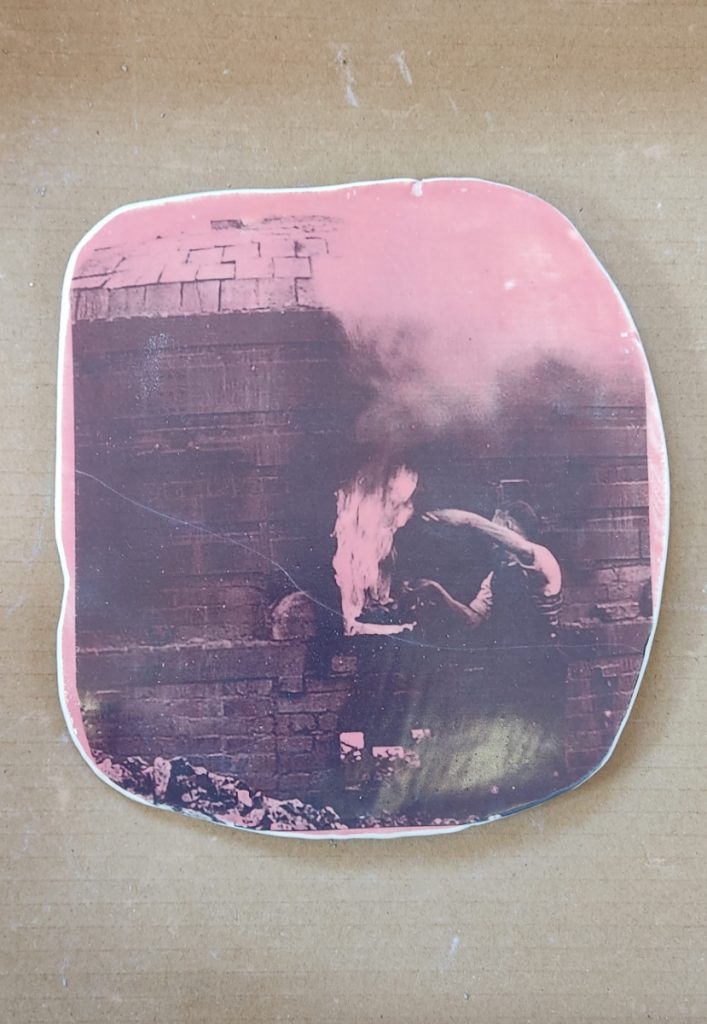

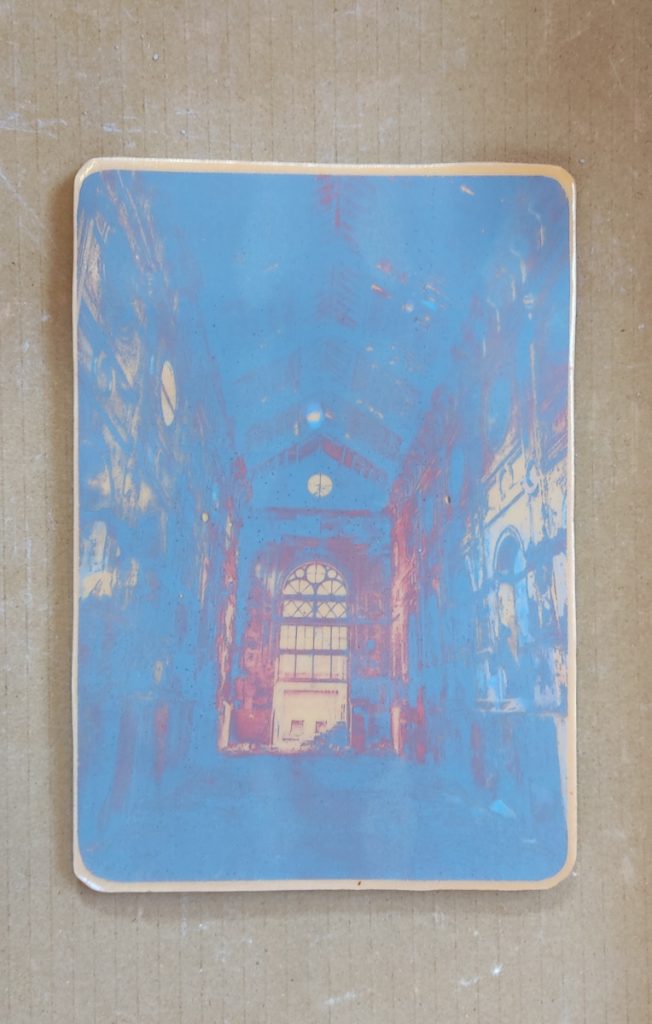

In building the juxtaposition, Neha explores the anecdotes of Trent’s active years where, on the days of kiln firing, the entire city skyline would be turned invisible owing to the smoke belched out of the factory chimneys. A ceramicist exploring the world capital of ceramics notes on one of the visits how she sourced ‘soot’ as a material for one of the works: “During one of my visits to the exhibition venue at all Saint Church, I was told about soot from the loose wooden floorings of the church. So, I carefully sourced some of it and used it to sprinkle and glaze the cloud-work, representing the change of the sky from the industrial time till today.”

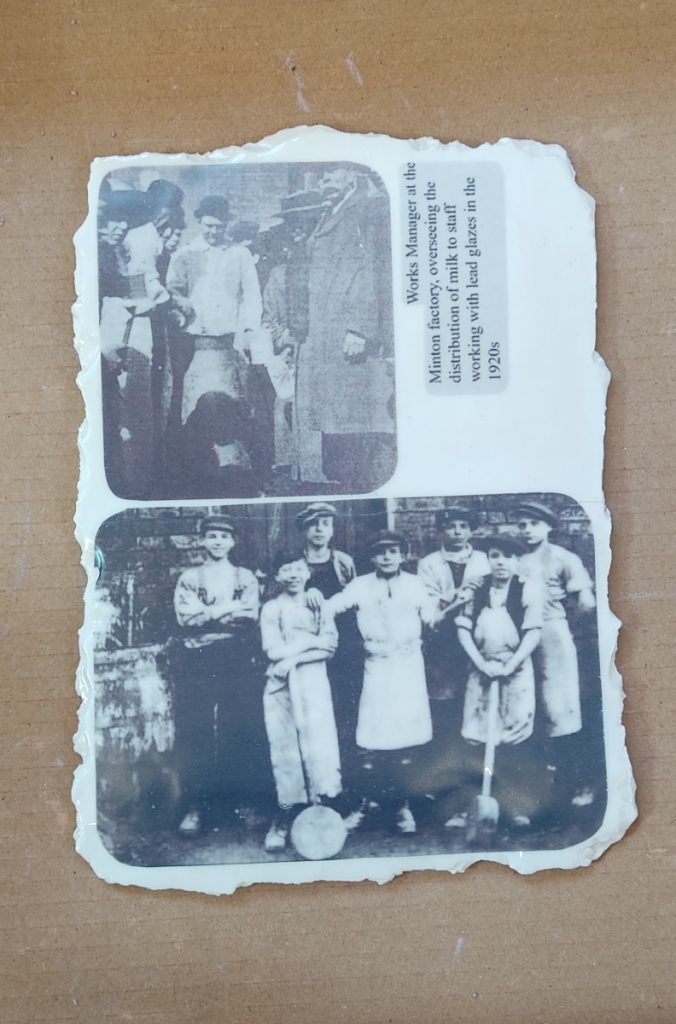

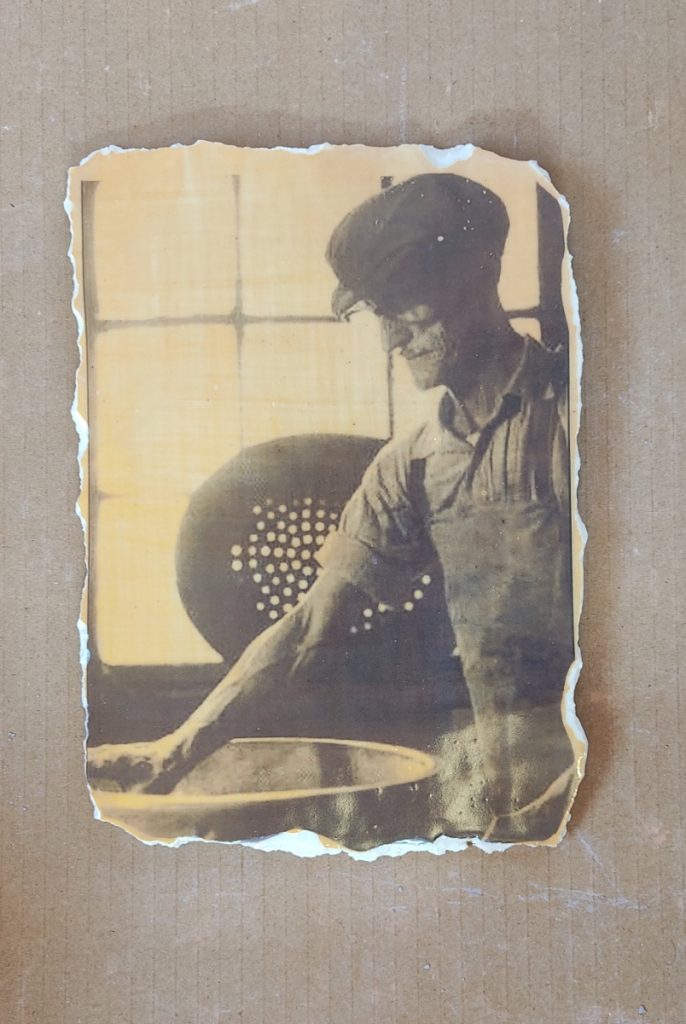

Amongst other works forming part of her sculptural installation are a miner-white and black porcelain hinting at the stature of the mining community, and the photo-transfers of the Saggar makers lend a comparative thought to looking at a sort of nostalgia and inquiry of the habitational constraints of the working class at Trent. Drawing parallels from the hazardous environments of industrial setups, one of the commonalities between Mumbai’s textile mills and the workers at the ceramic factories would be the handling and overexposure to the toxic materials used in the productions. Neha observes that ‘the young boys, of 12 to 14 years working in the factories as bottom knockers and concern of their mothers’ to avoid the employment of their children in chemically toxic environments that would shorten their lives.’ is a common and alarming matter that would demand setting up sustainable and healthy working environments.

“The dippers who would glaze the pots for several hours of the day. The glaze used was of lead, which would be poisonous to the health. Sometimes, they even worked with injuries to their fingers where direct exposure to wounds to lead would prove harmful.”

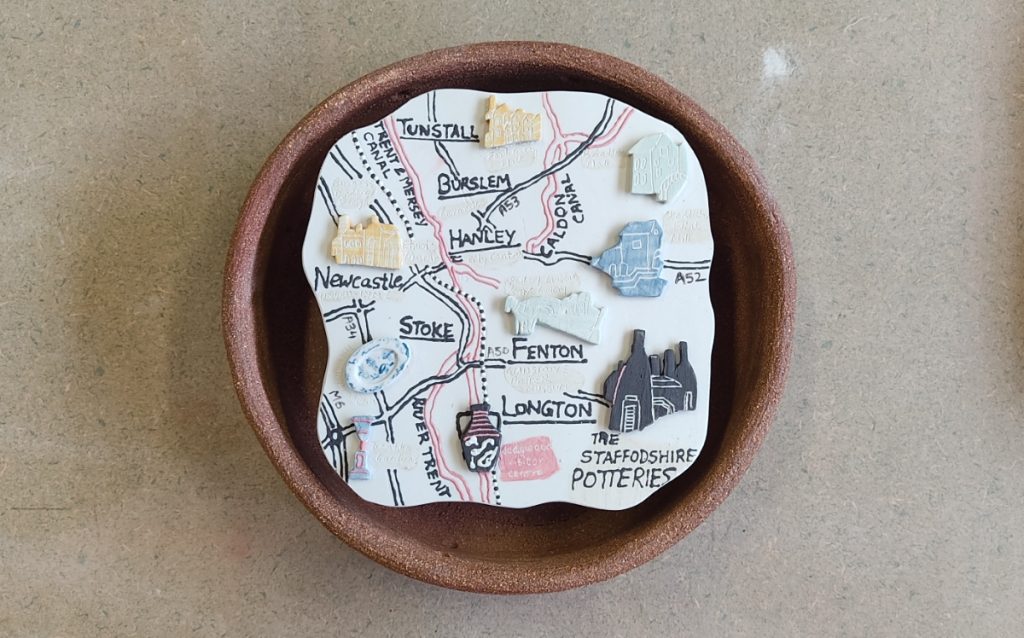

On a lighter note, she explores the iconic geographical changes of Macclesfield Canal – bridge and representation of the Gladstone pottery bottle kilns, and a ceramic map of the important ceramic sites at Trent brings about a curious sense of proposed nostalgia toward the place- a creative city.

In summary, the installation becomes a set of notes from different yet similar industrialized references that, by juxtaposition, present an aesthetic inquiry into the histories of the two cities, Stoke on Trent and Mumbai.

The residency in cumulation has allowed the artist to look at lateral creative models where her primary area of micro-architecture, social spheres, and industrial production in the wake of global eco-consciousness and material consumption.

The prime learning and direction for the artist, as she states, “This first international residency engaged me with understanding historical, cultural, social, and psychological factors of the present. Reasons for development and changes in the current situations. This enriching experience showed me how to introspect about my roots and the whole idea of presenting the past (irrespective of its glorious or the story of abolishing the inhuman practices for the betterment of society) in different ways. The impact or remains of a certain industry on the present generation and how people perceive it is what I intend to look forward to manifesting. How and where the stories of the past would lead is the inquiry keeps me invested in the thought process.”

Nikhil Purohit is an artist, art administrator, and founder of the organization Faandee Arts Archival Documentation and Research based in Mumbai.

Installation views by Jenny Harper