Part I. Salutations of Material, Exaltations of Materiality

Part II. Interview with Niels Dietrich

By Doug Navarra

When you arrive at Peter Freeman Inc Gallery in the Chelsea district of Manhattan, I ask the viewer to please leave your preconceptions of ceramic art at the door. This group exhibition of ceramics titled “Made in Cologne” is different for several reasons. If you are not familiar with these artists, it is because they are visual artists whose work may not typically be found in the field of ceramics. What is consistent amongst all of them is that they have come to the Niels Dietrich Workshop in Cologne, Germany, first and foremost to discuss ideas and then collaborate to produce work by an experienced team of professional craftsmen and technicians.

The artists include: David Adamo, Richard Deacon, Cameron Jamie, Alicja Kwade, Heinz Mack, Mike Meiré, Mai-Thu Perret, Otto Piene, Heinz-Günter Prager, Norbert Prangenberg, Thomas Schütte, Rosemarie Trockel, Paloma Varga Weisz, Rose Wylie, Anna Zimmermann.

It is important to look at this exhibition not only as fifteen different individual artists but also as an entire group of works that, in their diversity, make a statement in itself. These artists come together from different schools of thought, different cultural backgrounds, and different generations, harboring different artistic influences, and yet the appeal of clay is founded here in its versatility, allowing artists to explore the entire range of techniques the atelier makes available to them. It’s always a challenge to analyze an exhibition of this magnitude encompassing so many different approaches in order to understand the underlying elements that bind this entire exhibition together. Collectively these works represent a spirit of innovation and offer a bold departure from conventional and historic norms while celebrating the materiality of the ceramic medium. That very popular notion of materiality is one that continues to defy gravity. Conceptually, it reshapes and redefines the essence of ceramics in fresh and unapologetic ways.

As Michael Yonan writes:

“Materiality is therefore forever in flux, and materialities function differently within different settings. Imagining how an object’s medium fits within the philosophical, ethical, perceptual, and economic structures of a given moment is a way of understanding its materiality, and this produces a much broader and potentially more profound understanding of its historical significance.” 1

In looking at this exhibition, we are really attending to the broad structure that materiality brings into consideration; in essence, Michael Yonan suggests a theoretical approach that is time and situation-based. Naturally, we will further include ceramic materiality as the inherent characteristics of the clay medium itself. However, we should think of it with an expanding aura for interpretation beyond physical substance, including context, culture, history, and a discursive nature moving freely across different subject matter within this exhibition. I have long argued for a more anthropological foundation when viewing works of art from different lands to go beyond the limitations of our own cultural paradigm. This very diverse conglomeration of works in this exhibition grants a multiplicity of perspectives that presupposes an acceptance of materiality without such rigid constraints.

Beyond the more obvious physicality and tactile nature of the clay medium itself, Christina Murdoch Mills writes:

“[m]ateriality…. broadly encompasses all relevant information related to the works physical existence; the work’s production date and provenance, its history and condition, the artist’s personal history as it pertains to the origin of the work and the work’s place in the canon of art history are all relevant to the aesthetic experience.” 2

This has to be included as one of the seminal ceramic exhibitions of the season […]

As a matter of consequence, the exhibition conveys an “architecture of openness” that guides us not only to deeper levels of understanding, but to how we consume those very aspects of understanding from the world around us. This exhibition portrays a materiality that affects how viewers are engaged emotionally, intellectually, and sensorially. I would say this has to be included as one of the seminal ceramic exhibitions of the season in New York’s Manhattan art galleries today.

In this exhibition, Mike Meiré is represented by a small group of floor sculptures. These are, in a sense, tropes of containers, some of which you might think are upside-down, opened up then cut in half, or halves joined. They appear to resemble the collective likeness of buckets, pails, or washbasins. They interest me in their Pop appropriation of bright (in this case, low-fire commercial glaze) color usage and thick clay walls. Their handling in their press-molded fabrication veers away from a tightly conceived technical perfection yet allows for a casual, meaningful orchestration of voice.

Materiality and discourse are so intertwined that they offer a performative reality configured not just as bodies in space, in this case literally on the floor, but also those spaces between the objects. These forms are relational to each other, but there is still this dialectic of back-and-forth visual interplay between forms and spaces, much like a dance.

Yet these finished pieces in themselves become passive signifiers in a semiotic way, defined not wholly by their finished, fired and glazed appearance, but by their association to the once representational forms they were cast from. Now cast as material symbols, they refer to pre-existing concepts of function and utility. Physically and visually, we can see these represent surgical operations of form, but what we are left with conceptually are figures of speech that offer different varieties of relationality.

This is a good entry point to underscore much of what is happening in Meiré’s work within this group exhibition. The interpretative implication of materiality is being recognized “as collaborator”. I mean that the aperture of intention readily accepts material qualities involving textures, the odd character of a brushstroke, craquelure, unintended firing cracks, lipid translucency, and a recognition of malleability and random process marks as acceptable investments. Material and process are being realized as an active participant.

Worth noting, materiality accepts these deviations from established norms as they are retained as distinctive features or characteristics that arise during creation, further portraying the unpredictable story parts of the maker’s journey and the intrinsic nature of the medium. From this acceptance of process as contributor and collaborator, it is, in fact, an elite and sophisticated type of freedom.

Another artist in this show is Cameron Jamie, who I do not think one can speak about without understanding a bit about his early background and experience growing up in the San Fernando Valley of California. This experience, so profoundly influential, he has articulated by calling his teenage years:

… “horrible,” “a very small and dead world,” and akin to “a maximum-security prison,” where a landscape of ubiquitous shopping malls felt like “the end of humanity.” 3

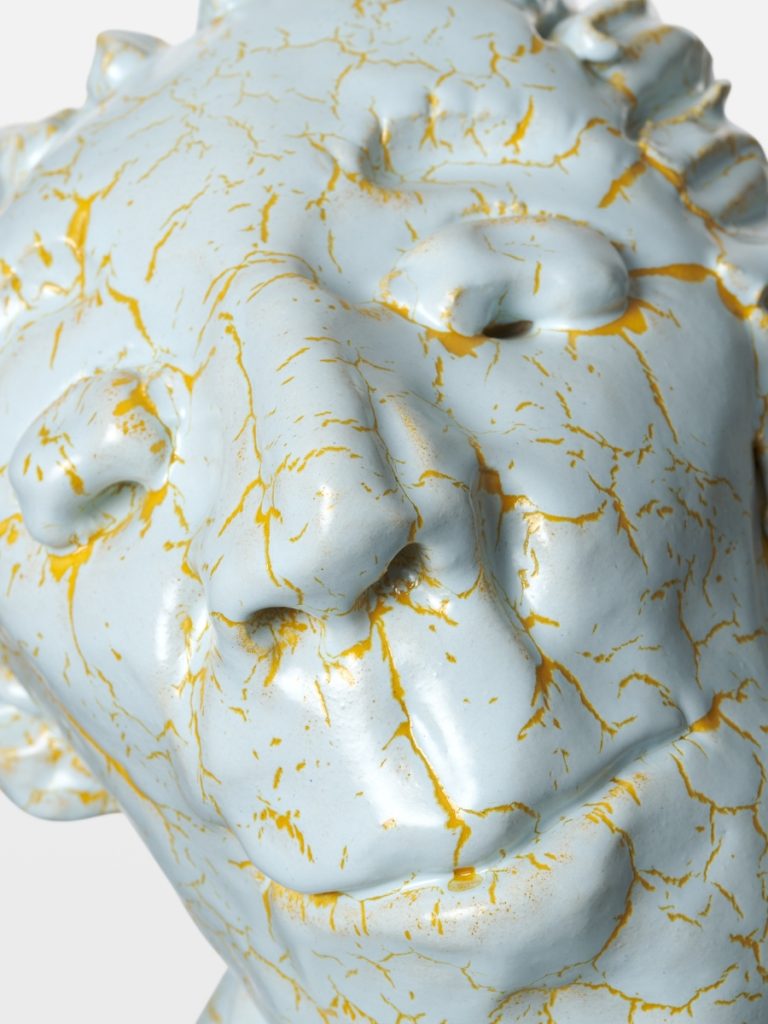

In a way, it explains not only his departure to Paris in the year 2000 but also reflects the conceptual responses from which his works originate, thus twisting, reinventing, and reconfiguring that sociological macabre founded in the dysfunctional spectacle of suburban life. In different ways, it permeates throughout his entire oeuvre, whether it be his films, drawings, or ceramic sculptures. It is actually a blend of investigative tactics arranging for a vitality that reacts against the role of negativity. In accord with these early founded ontological apprehensions, there is a very positive energetic reaction that is overlayed and dominates. It also emphasizes the role of how materiality is being conveyed. This morphology becomes the difference-maker guiding the art into a non-representational dimension. His ceramic sculptures depict a destitution of and genesis of form at the same time, which underscores a meaningfulness that we might typically find in materials that are pre-symbolic.

That attribute of a “genesis” appeals to me because these works challenge traditional notions of representation. They evoke ambiguity, aspects of chaos, and rawness that I believe he sees emanating from his early experience with suburban folklore and vernacular traditions.

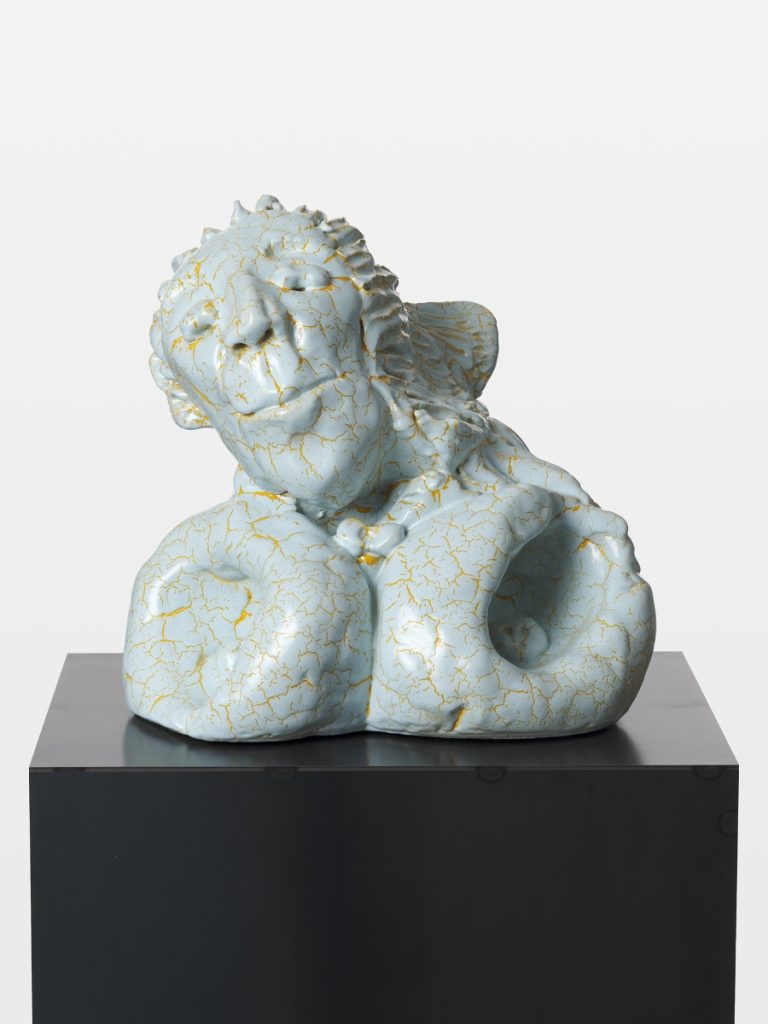

In this series of ceramic forms, these biomorphic apparitions with polychromed glazes are composed of curvilinear forms typically conveyed in two parts. The bottom half depicts a sense of organic natural growth, blurring the distinction between nature, abstraction, and imagination. The top quadrants assume more of a conflated gestural spectacle. This is the primary element of these sculptural apparitions, which are the culmination of his territorial investigation, where psychic forces appear ready to explode, challenging any notion of conformity while offering glimpses of existential transformation. They are unique.

The exhibition is also gifted with two works from the Norbert Prangenberg (1949-2021) Estate. One large freestanding work is titled Rosenzweig, and the other is Untitled, a wall-mounted band of clay coils. These are studies that map out spatial volume. ‘Rosenzweig’, for instance, has no bottom, even though it may look like a container. Prangenberg’s ‘Untitled’, wall-mounted coil structure, like much of his work, is a critical investigation of inner and outer spatial volume. Figuren, a title that he often used for many of his freestanding works, is not a reference to an anatomical view of the human body but an enigmatic aggregation of volume in space. These works have no functional purpose but they do possess an inner and an outer periphery.

The Art Daily exhibition review from Karsten Greve Gallery in 2017 describes the works’ visual acumen:

“Akin to the outcome of an eruption, bulbous, porous walls covered in rhythmical eversions and protuberances become manifest in the artist’s Figuren. Appearing to result from the elements’ fiery discharge these outbursts often assume a decorative appearance, resembling floral traits.” 4

However, these works are way beyond the visual; the outlines of these forms are the meeting of planes, inner and outer. It implies a psychology where positive and negative space are better understood as occupied and unoccupied. Volume may represent the physical space that a sculpture occupies, but given the works have perforations throughout, they intentionally incorporate openings and voids to allow for space to pass through them. These works are not just physical indicators of where inner ends and outer begins; they also represent conceptual domains that articulate volumetric spatial concerns. Possessed by frontier margins that demarcate between inner and outer domains, this “inner space” is all Norbert Prangenberg. It is where authenticity resides. Most importantly, inner is an autonomous space emphasizing the intrinsic volumetric independence as art for art’s sake.5 Crossing that threshold between inner and outer signifies a transition into a different, perhaps more profane mode of being where space radiates from a central core. But the inner in itself, challenges our traditional notions of utility and function. It is devoid of any practical function or instrumental value. It cultivates a deeper connection with the whole idea of art. It is the critical distinction that lies in the purpose behind the work itself. The surrounding outer space does not exist infinitely but is filled with a cosmic symphony of radiance, the whispers of photons, and echoes of an ancient light. Materiality incorporates all of the inner and outer spheres.

There are so many great artists in this show, Thomas Schütte included, who will, by the way, have a solo retrospective exhibition this fall at MOMA. The international artist Richard Deacon is represented by some truly magnificent works. Berlin-based artist Alicja Kwade, who one may be acquainted with from her 2019 installation on the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden at the Metropolitan Museum is also represented in this exhibition.

In summary, the exhibition highlights the interplay between the raw physicality of the ceramic material and the external influences that shape its design and meaning. These examples demonstrate how ceramic sculptures can serve as powerful vehicles for conveying a materiality of our time. As a group exhibition, it is one that challenges our traditional conventions, celebrates idea, and invites us to explore the conceptual nature of these works on view. It is jam-packed with exceptional works by exceptional artists.

Read Part II. Interview with Niels Dietrich

Doug Navarra is a visual artist who has an extensive background in working with clay. He lives in Hudson Valley, New York.

Made in Cologne: Fifteen artists working at the ceramics atelier of Niels Dietrich is on view at Peter Freeman, Inc. through July 19, 2024.

Sign up for Ceramics Now Weekly if you’d like to read similar articles on contemporary ceramics.

Captions

- Installation views Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc. Photography by Nicholas Knight

- Mike Meiré, Red Bucket Divided, Piled Up, 2024. Photo credit: Mareike Tocha

Mike Meiré, Mint Box, 2024. Photo credit: Mareike Tocha - Cameron Jamie, The Observer, 2024. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight.

Cameron Jamie, Wildflower II, 2024. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight. - Norbert Prangenberg, Rosenzweig, 1998. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight.

Norbert Prangenberg, Untitled, 1993. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight. - Thomas Schütte, Geisha, 2024. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight.

Thomas Schütte, Monk, 2024. Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photography by Nicholas Knight. - Alicja Kwade, Blue Journey, 2023. Courtesy the artist

- Richard Deacon, North – Blue Water, 2007. Photo credit: Hans Ole Madsen

Further reading

- Van Oyen, Astrid, “Material Agency”, Wiley Online Library, 11/26/18. Link

- Orlikowski, W. J. and Scott, Susan V. (2015). Exploring material-discursive practices. Journal of Management Studies, 52 (5). pp. 697-705. ISSN 1467-6486

- Ingold, Tim (2013). Making Anthropology: Archeology, Art and Architecture, p.27.

Footnotes

- Michael Yonan, “The Materiality of Porcelain and the Interpretation of Ceramic Art”, The Journal of the Walters Art Museum, Volume 75.

- Mills, Christina Murdoch, “Materiality as the Basis for the Aesthetic Experience in Contemporary Art”, University of Montana Graduate thesis. Link

- Joseph, Brandon W, “Minor Threat: The Art of Cameron Jamie” ArtForum, Oct. 2014, Vol 53, No 2

- Art Daily.org. Exhibition Review, Karsten Greve Gallery, Cologne, Germany, Jan 3, 2017

- Immanuel Kant did not explicitly use the phrase “art for art’s sake,” but his ideas align with this concept. In his influential work, The Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant emphasized that the ultimate goal of art was to provide an enjoyable experience independent of any utilitarian or moral concerns.