By Jennifer Zwilling

Clay is the future and the past. The earliest examples of fired ceramic objects are 25,000 years old; ceramics made today will endure well beyond 25,000 years into the future. Ceramics may very well exist on this planet long after biological life ends, as a fired piece of clay is among the human creations most immune to environmental change. Therefore, perhaps one of the futures of clay is simply that it will remain.

We know that ceramic objects have long been used as valued carriers of the physical life of the community, its water and food, as well as its intellectual life – its culture. The adorned surfaces captured information about what the community valued, its concepts of beauty, and the technology it possessed, indelibly transcribed onto their surfaces to be communicated eons into the future.

Thinking about ceramics from the past in relation to dynamic contemporary artists working in clay raises intriguing questions: How do contemporary artists working with clay represent our cultural moment? How will the ideas of the early 21st century be interpreted in the future? How will the use of clay to make art evolve as our culture and technology changes so rapidly?

These questions form the core of our exhibition, which aims to examine the future of this ancient material. To fully embrace this concept, we reimagined our curatorial approach. We invited three co-curators to join me in envisioning an expansive definition of the future. Our varied experiences and perspectives allowed us to explore the question, “What is the future of clay?” in ways that a single curatorial voice could not achieve.

This four-person curatorial team represents a new format for our exhibition design process. Each curator proposed artists they believe are creating artwork that speaks to the future, while also reflecting the diversity of contemporary ceramic art. After thoughtful discussion, we invited eight artists who we felt embodied the future of ceramics, and who had never before exhibited in The Clay Studio’s gallery. Their work represents a range of techniques and aesthetics from computer-aided design with bright colors, to hand-dug clay with earth toned, burnished surfaces.

Our curatorial team initially anticipated that a main theme would emerge among the works of the eight selected artists, and provide insight into where the field is heading. Each curator held studio visits with their chosen artists, and then shared their findings with the group. As conversations with artists progressed, and works began to take shape, no single theme materialized. Instead, the multiplicity of how the artists visioned the future became the theme. Our process revealed that there are many futures of clay that have emerged from many pasts.

The artworks in the exhibition reflect the myriad ways that artists are using clay to communicate their ideas about the future, including: computer aided design and manufacture (CAD/CAM), indigenous futurisms, climate activism, transnationalism, challenging the cultural status quo, parenthood, and honoring the past to truly understand the future.

In addition to examining how the artists are visioning the future, as a curator, my future-forward thinking must also focus on how we can innovate the systems underpinning how we exhibit artwork. A crucial, often overlooked aspect in exhibition design is the role of the viewer an essential component of the artwork. The audience should be considered, consulted, and centered throughout the exhibition design process. For The Future of Clay, this philosophy began with expanding our curatorial model from a single curator model to a team of four, allowing us to gain a broader perspective of the question “What is the future of clay?” While the curators defined the concepts and chose the artists, we sought to widen the conversation further. To gain insight and feedback, we invited key staff members and our Exhibition Council – comprised of local neighbors, fellow artists, and other stakeholders – to share their ideas about the future. In a later chapter you’ll find responses to the artworks from some Council members.

Cesar Viveros, a renowned mural artist, sculptor, community activist, and neighbor, joined our Council since its inception in 2018, as we began plans for our current building in the South Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia. For six years he has been a generous and active member of the Council, attending meetings, and giving valuable input into our exhibition ideas for the last 6 years. Viveros’ connection to clay runs deep, rooted in childhood memories of shaping wild clay from his grandparents’ land in Mexico into vessels and figures that echoed the ancient ceramic fragments he discovered there.

When Viveros expressed his desire, enduring through his life, to resume working with clay, we seized the opportunity to facility this through our exhibition. As a Guest ARtist in the summer of 2024, Viveros collaborated with our staff to bring his vision to life. Despite the years away from the medium, he created impressive sculptures. Through the series Hijos de la Tiznada, he was able to communicate his vision of the future by using the material that first awakened his creativity when he was a child. In a full circle moment, Viveros brought his son to work with him in the studio this summer. Shaping the clay together helped Viveros and his son talk about their heritage, their family, and their future. Hijos de la Tiznada thus represents the fusion of Viveros’ heritage, artistic expression, and his family.

Jolie Ngo’s work in the exhibition is perhaps the easiest to connect with the future. It is made with the use of a computer-aided design program and some aspects of it are produced by a 3D printer. These tools are just that, tools to help an artist’s vision exist as a tangible object. Ngo skillfully uses them in a way that does not overshadow her creative agency. Just with an electric pottery wheel, this is a technology that once could not have been fathomed, and is now becoming a common production method. Ngo is interested in these tools, but is careful not to let the production method become the raison d’être for the artwork. The sculptures are fired multiple times, with Ngo’s complex colors and patterns applied through exacting techniques she performs after the works are printed. She adds lustered glaze drips and metal ‘jewelry’ to further emphasize that the printing is only one of many processes utilized to create the works.

Drawing inspiration from vessel forms and Vietnamese lanterns, Ngo’s sculptures pay homage to her cultural heritage.. The vibrant colors and luminous glazes reference the glow and bright colors of lanterns, and the vessel forms acknowledge the utilitarian foundation of ceramic traditions. The fusion allows Ngo to, in her words, “Smile toward the future,” while grounding her work in the value of the past. It is precisely the tension between the handmade, and the digital, the traditional techniques versus the new technology that Ngo is exploring and exposing. Visitors to the gallery are drawn to the bright colors and (for some) the new visual of the 3-D printed layers. They are fascinated to learn about the process, but have many questions, like whether these new processes will someday supplant handmade modes of production. Evidence from past technologies (like the aforementioned electric pottery wheel) have taught us that 3D technology will simply become one of many tools, allowing artists more freedom of expression. Jolie Ngo’s work sparks rich conversations about culture, contemporary discomfort with technological integration, and the future role of artists as innovators, and models of what humanity can achieve through creativity.

Excerpt from an essay by Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy

Kristy Moreno’s work looks like the future. Her hyper-stylish femme characters often wear garments akin to spacesuits and intergalactic uniforms with cosmic hairstyles, makeup, and accessories. For decades, outer space has informed the concept of futurism—from the Space Race and Moon landing, the many popular cinematic franchises it has inspired, such as Star Wars and Blade Runner, to the recent space travel of celebrities and billionaires. For many scientists, the future of humanity lies somewhere among the stars. But within Moreno’s Zenon-the-twenty-first-century-girl-meets-Chicana-fashion futurist aesthetics is a truth deeply grounded in our earthly realm: the strength and perseverance of community.

Michelle Im has been reflecting on the immigrant experience and her identity as Korean American in her new body of work while maintaining her joyful and sincere approach to making. This series includes a sculptural flight attendant in the style of a Qin Shi Huang Terracotta Army warrior. Although she has only sculpted one so far, she plans on making more. Her army of ladies, with polite smiles, pristine uniforms, and uniquely colorful hairstyles, will be formidable. For Im, who has traveled back and forth between Korea and the United States, the Korean Airlines flight attendants are guardians and guides of transitional moments and spaces. A symbolic figure that Im has materialized as she experiences meaningful change in her practice.

Excerpt from an essay by Anya Montiel

Chase Kahwinhut Earles, an enrolled member of the Caddo Nation, has become well known for his works that touch on Indigenous Futurism, an art and literature movement that indigenizes science fiction and alternative futures. He has created Caddo versions of Star Wars characters such as Yoda, Boba Fett, and BB-8. The work in The Future of Clay, Scout, resembles an Imperial droid used by the Galactic Empire to search for enemy groups. By titling it Scout, Earles is alluding to the military practice of the U.S. Army in hiring Indigenous scouts to detect so-called enemy tribes. Earles views his Indigenous Futurism works as a continuation of Caddo pottery. “It’s about showing that Native Americans are not stagnant,” he explains. “We don’t just produce old ancient things for nostalgia. Our Native culture can be woven in and seen as modern-day pop culture, as well.”1 This highlights that Indigenous cultures have always adapted and transformed, taking in new technology and tools that benefit their communities. In considering what clay symbolizes, he remarked that, “Clay attaches you to a place. It can bring you back to your people and your culture. It grounds you to the earth.”

Like Earles, Holly Wilson’s work has elements of futurism, but for her, “futurism isn’t sci-fi for me. It’s about this next generation. It’s what you’re passing down…that’s why I think about my kids and using them as the models, because everything now that I do is informed to me by what my kids will be able to experience or have or do.” Especially evident in her human figures with short torsos and long limbs, they are expressions of her children and that time in youth where the body is growing and building at different rates. In them, she captures those moments of play and raw vulnerability. She explains, “What I love about clay is that it’s like flesh or skin. It feels so human when you work with it. Clay has all these different colors and shades. Clay cracks me up, because it’s so temperamental but at the same time, it’s so forgiving. It’s very much like a body, like a person.” Based in Mustang, Oklahoma, Holly Wilson is an enrolled member of the Delaware Nation of Oklahoma and a descendant of the Delaware Tribe of Indians.

Excerpt from an essay by Zindzi Harley

Through her practice, Philadelphia based, Nigerian artist Anne Adams redefines what it is to be African, dismantling cultural stereotypes, and collapsing conventions such as time, place, and race. Adams transcends the misconceptions of African art, decolonizing the prejudiced idea of it being solely based in ritual, and religion rather than intellect, skill, and craftsmanship. In preparation for the “Future of Clay” exhibition she has drawn from archival photography from the British pre-colonial administration in Nigeria particularly from the famous ethnographer N.W. Thomas, a famous ethnographer whose work has prompted new questions for the artist. Adams’ asks “How do I reinterpret and counter this archive to demonstrate these people have agency over themselves?” Through her work in the exhibition “A Congregation of Elders,” Adams finds the answer partly in looking to the future of clay and its hybridity. It’s all about creating a vessel for taking traditional ways of learning and contemporary discourse to engage African culture with a global influence. We might wonder, “How can clay exist in conversation and form alongside different ideas and mediums?” The answer is a mixture of nature, technology, and human connectivity that will lead to the future of clay.

Morel Doucet’s sculpture and visual poem, The Blueprint (Indigo Wing & A Poem Full of Corpses), is an eerily beautiful artwork that explores the relationship between humanity, nature, and the consequences of our actions. “The Blueprint” addresses the impact of humans’ environmental footprint and the destructive path it has created as a result of our neglect and lack of awareness in our engagement with the natural world. This work also embodies the essence of hybridity in it’s death and potential for rebirth. Drawing from the harsh realities of South Florida’s rapid climate change has impacted not only the terrain and geography of the region but the lives that inhabit it. Doucet asks viewers to utilize the blueprint in rebellion of these environmental challenges and reflect on the loss of life and opportunity for growth through conscious action and healing. Morel hopes that we will reconsider the paths that we follow; it is never too late to be mindful of how they cultivate hurt or harmony with the environment. This visual poem is a moving and magical reminder that we may rewrite the narrative of devastation to one of regeneration, a hopeful nod to the poetic justice that is served when we look towards the future.

In conclusion

As The Clay Studio celebrates its 50th anniversary we are considering our future as we honor our past. Ceramic art represents a link between the past–in the continued creation of simply decorated vessels–and the future–through new applications of computer aided design and 3-D printing. In each iteration ceramic art is used as a vehicle for cultural expression, and can communicate a full range of social issues, from things we celebrate to things we fear. The Clay Studio has spent 2025 in remembrance of our past. The Future of Clay is our way of concluding this year in honor of our next fifty years, by reiterating our mission to serve artists and community, continuing to stay relevant, investigating what is exciting in clay right now, and being open to its potential to change in the future.

Jennifer Zwilling is The Clay Studio’s Curator and Director of Artistic Programs. She earned her BA in History from Ursinus College and MA in Art History from Temple University, Tyler School of Art. Previously, she was Assistant Curator of American Decorative Arts and Contemporary Craft at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Jennifer developed and taught History of Modern Craft at Tyler School of Art for ten years and has taught and lectured around the world.

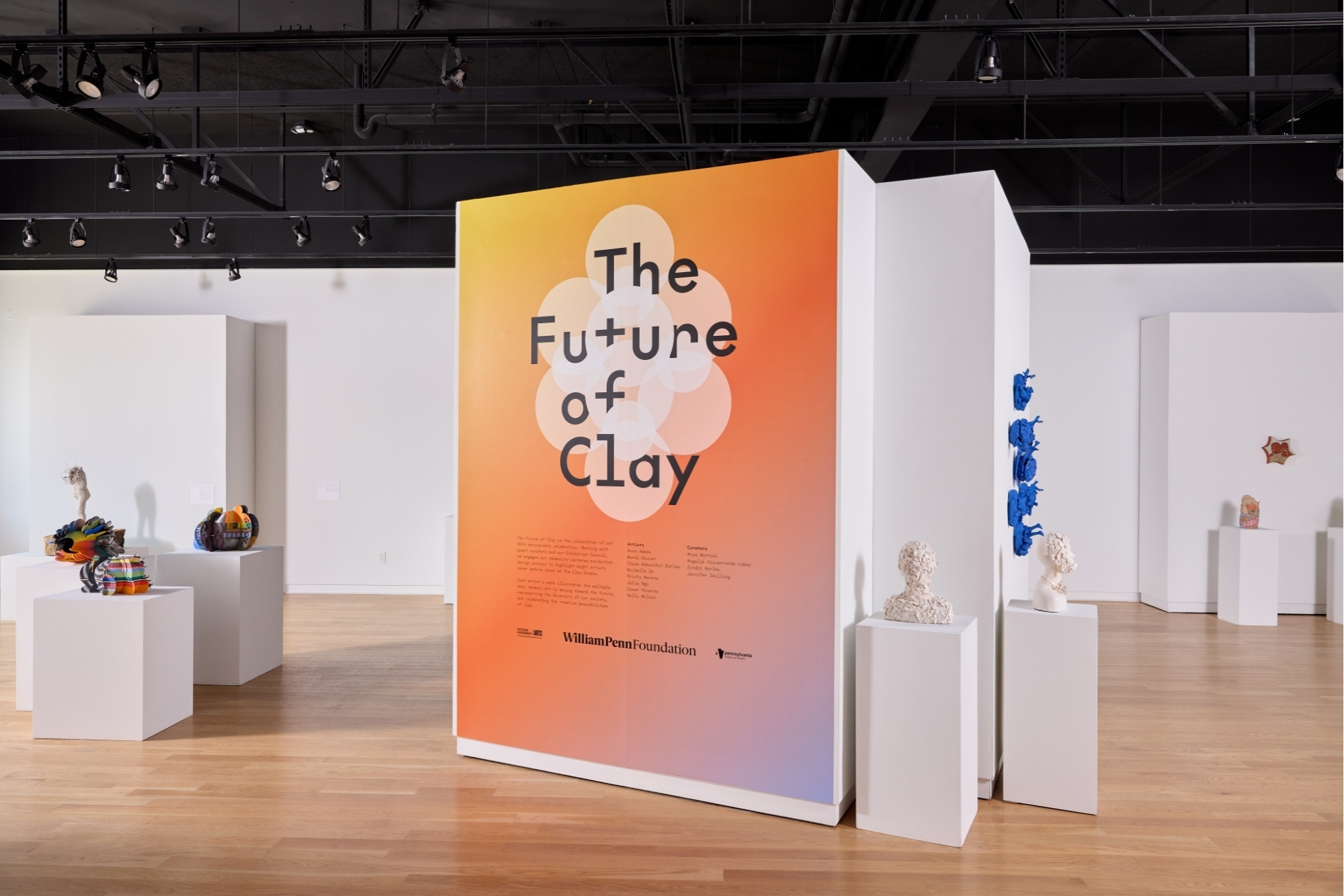

The Future of Clay is on view at The Clay Studio, Philadelphia, between October 5 and December 31, 2024.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Photos by Alexander Mansour

Footnotes

- “49 Minutes of Fame Artist Profile: Chase Earles,” The National Willa Cather Center (November 18, 2021) Link

Comments 1