By Kristina Rutar

Ceramic’s very nature as a material dictates the way we handle and interact with it, namely gently, cleanly, and never too roughly. When on view in galleries and museums, an additional sense of distance is created, often through the physical barrier of a glass case, a marked-off region beyond which it is alright to stand and look, or even just through a security guard’s dirty look as you approach a piece. An ironic relationship is created with ceramics – before firing, when it was still clay, it was a material that invited you to touch it, knead it, and engage with it in a process of constant forming and reforming. As a rigid, unmalleable, and impermeable material, the object’s worth depends on its form or its ability to fulfill its intended purpose. It maintains that worth as long as it retains its form, but when reduced to shards, it becomes an object to be discarded, as it can no longer serve its purpose, and the shards have no purpose to begin with. We have all internalized these concepts, which we constructed as a society through our widespread interaction with ceramics in the form of, for instance, tea sets and other table accoutrement, to the extent that, as artists, we often feel constrained and, by habit, approach clay and ceramics as primary materials with certain rules about their handling. Seeking seemingly silly connections and challenging our own perception of a focus material is thus likely one of the only ways to transcend our conditioned, perhaps even ignorant understanding of clay and ceramics.

The inherently contradictory epithet “kinetic ceramics” invites a range of new perspectives on the wealth of characteristics that clay and ceramics offer as media. If you follow the material’s development from its initial, hard state, as a block of solid clay that can be cut, crushed, or mixed with water until it becomes a thick, sticky, fluid mixture, which upon contact with an absorbent surface transforms into a malleable mass whose texture can range from rough to slippery. That mass can then accept imprints, it can be guided and molded, it can be added to, and it can be halved.

Upon drying, this mass, which has been in constant flux so far, finally receives a hard, though fragile form. Although the drying and firing processes give the impression that the medium has now undergone an irreversible thermal process that has locked them in their pose, even that is not the ultima thule we might think: unseen to our eyes, the clay is still mutable. The edges of its clay particles melt and merge. A vitrified bond forms between the particles, rendering the object solid and impermeable. And even then, there’s still no end to the material’s constant metamorphosis. Even after firing, ceramics are in motion. The glaze cracks—a gradual, long-term process that, even if microscopic in small intervals, nonetheless adds up to a physical change in the object. A more extreme example is found in dunting, the way ceramic shards crumble due to a mistake in the firing process, either from uneven heat distribution in the furnace or from cooling off too quickly. The resulting cracks, which at first are perhaps merely a hair’s width, eventually cause the object to collapse, even if it was never used or handled. And an object’s collapse, its fragmentation and disintegration, means a return to the earth. The tribes of Malawi, for instance, fire their earthenware to the point where it’s hard enough to use but still soft enough to be remodeled and recycled into a new form. All these things considered, it’s safe to say that the flow of motion and life through and within clay and ceramics is never interrupted.

The many techniques that can be applied to the material through its various states and stages allow for a gamut of artistic approaches and forms of expression that only attest to the clay’s generosity as a medium to work with. When we free our understanding and handling of the material from the shackles of convention, we can be swept away in their ensuing current, recognizing their true nature, which becomes alpha and omega in the process of creation. At this point, the material itself becomes a translator or interpreter of a concept, an idea, independent of any historical milieu or artistic classification. The dialog between the kinetic and the ceramic becomes a closed loop of transforming characteristics in a broader context, and the potential for expression extends to the domains of performance, multimedia, concept art, and interdisciplinary projects.

The British Ceramics Biennial (from now on BCB), with its wonderfully curated exhibitions, showcases the most cutting-edge concepts and out-of-the-box projects, which playfully toy with how we perceive materials, encouraging others towards critical contemplation about the social, climatic, and otherwise global changes of the modern era. I am specifically highlighting BCB here as one of the world’s best and most influential international exhibitions, one that sets the bar and shows the way forward, always displaying the most progressive intersection of clay and ceramics with modern art. Here, I would like to highlight the artists Caroline Tattersall, Phoebe Cummings, and Juree Kim, whose way with clay is anything but conventional. They subject clay to many states and conditions, triggering changes in the material itself and thus in its ultimate form. Their act of transformation could be characterized as a performance of the material itself as a living entity. Caroline Tattersall’s work Spode Towers takes old molds of jugs from the industrial ceramics manufacturer Spode and casts porcelain with them. She then stacks the result into a mighty tower, filling the highest jug with water, which then seeps through the pores of the poorly connected forms until they are destroyed. This work is intimately related to the collapse of the domestically and globally influential Spode factory and, in the broadest sense, to the consequences wrought by the closure of its factories – a rise in unemployment, a loss of tradition, and a fracture in the continuous dissemination of knowledge to a new generation.

Juree Kim depicts collapse even more poignantly, setting a row of carefully sculpted houses on a wet surface. In her piece Place and Practices (2017), the water gradually dissolves the bottoms of the sculptures, leading to their slow but inevitable disintegration. Juree Kim’s work explores social and natural environments, focusing on her own cultural identity.

On the other hand, Phoebe Cummings creates statement pieces that funnel clay into its own separate ecosystem, where it can be self-sufficient and independent of external influence. This effect is achieved by sealing off rooms, as in the case of her work After the Death of the Bear (2013), where tropical details are emphasized. The water that evaporates from the surface returns to the clay as dewy droplets of condensation. The process continues indefinitely, a timelessness accented by the blurred, foggy vantage point through the wall of polyvinyl film.

Indeed, the British Isles are blazing the trail in the modern development of new techniques and approaches to clay and ceramics. Other artists like William Cobbing and Keith Harrison opt for more direct, performative acts. A material becomes kinetic as the direct result of a protagonist’s impulse, of an intentional, conscious action. William Cobbing produces clay masks or heads that assume the role of vessel for the action that will ensue from an actor’s impulse. Whether through cutting, manipulation, folding, writing, or deletion, the clay head becomes a chimeral entity, while the identity of the action’s driver remains anonymous. Works like The Kiss (2017) also make historical reference to the work of Constantine Brancusi. Grotesque heads melded together, mounted atop a human form, with arms tenderly caressing the sticky, slippery surface of the clay, is a translation of the primal, archetypal conception of the power of the kiss that Brancusi referenced in his own series with the same name.

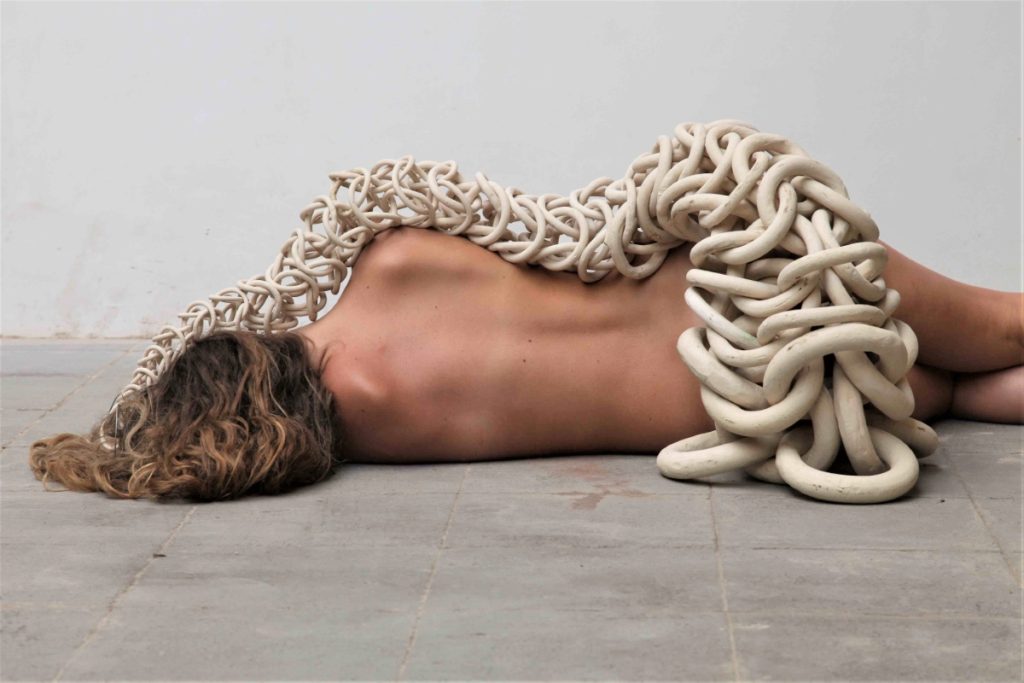

This direct, physical relationship is an even more prominent feature in the work of Alexandra Engelfriet, a Dutch artist whose creative process fluidly weaves between production and performance. Her work is that of dialog between two opposing forces or masses. Their relationship marks both parties equally, with the ultimate result in sculpture and room-sized works, as well as in graphic prints. Her work Skinned (2018) employs a constant influx of material to explore the very concept of space, along with its demarcations, and thus also with the borders of our own bodies. The performative endeavor results in body-shaped imprints on the gallery’s walls, which assume the very identity of said imprints. The coarse layer of clay left behind becomes an archive attesting to the changes the space underwent. Alexandra Engelfriet, who is viscerally and bodily connected to the material she works with, ironically and contradictorily keeps an extraordinary distance from it – her work is always about the effect of one material or one body on another.

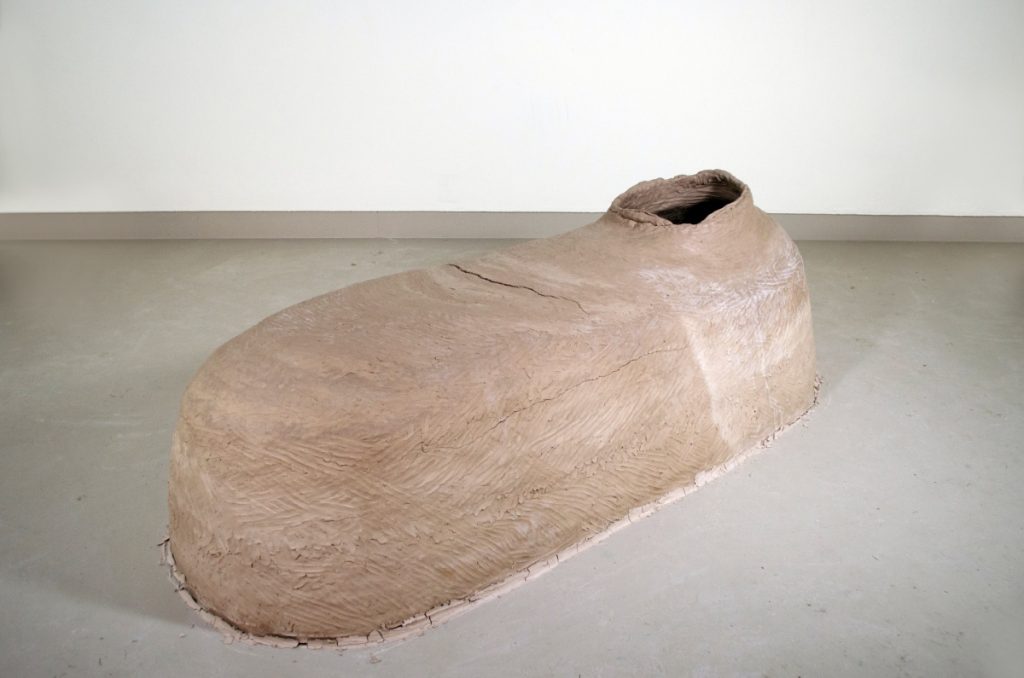

Taking a completely different approach from Alexandra Engelfreit’s, Marisa Finos understands clay and other materials as an extension of the body. It’s not about a dialog and a mutual enterprise of two masses but the harmonized, synchronized, and supremely conscious construction of the new form that the material must assume. The artist bestows upon clay the role of constructing the invisible but personal boundaries of private space. Her inspiration is drawn from an understanding of death and dying in modern culture. The shaped sarcophagi (Vessel, 2014) and domes (Vessel III, (With Harriotte), 2015 ) that she created manifest a safe space for conducting rituals related to the concepts of afterlife, ancient and modern funerary practices, funerary structures, mourning rites, and the corpse’s preservation and ultimate decay.

Teri Frame, Pre-human, Pos-human, Inhuman, Act III: Hybrids

Teri Frame, Pre-human, Pos-human, Inhuman, Act VI: Post-humans

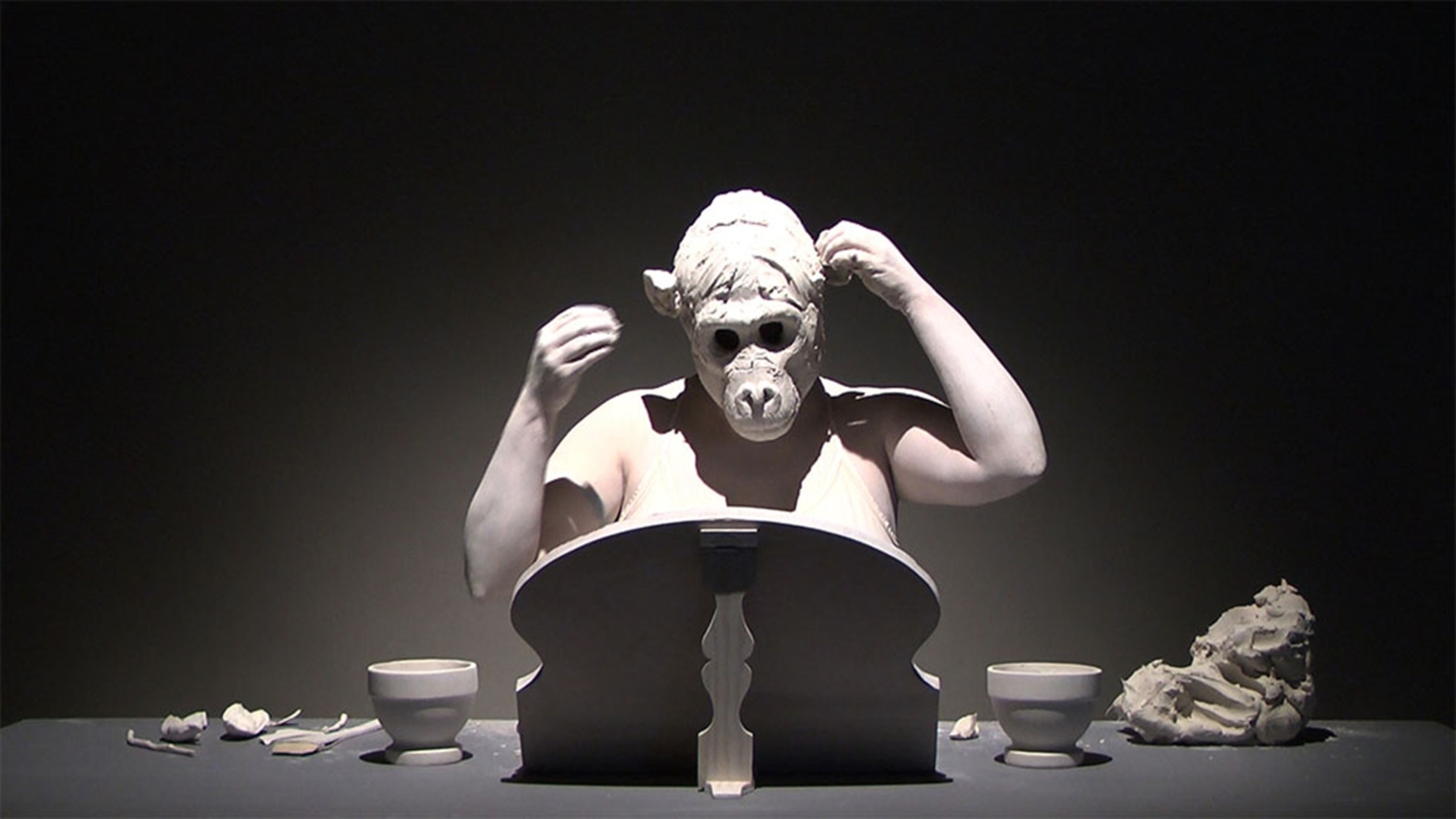

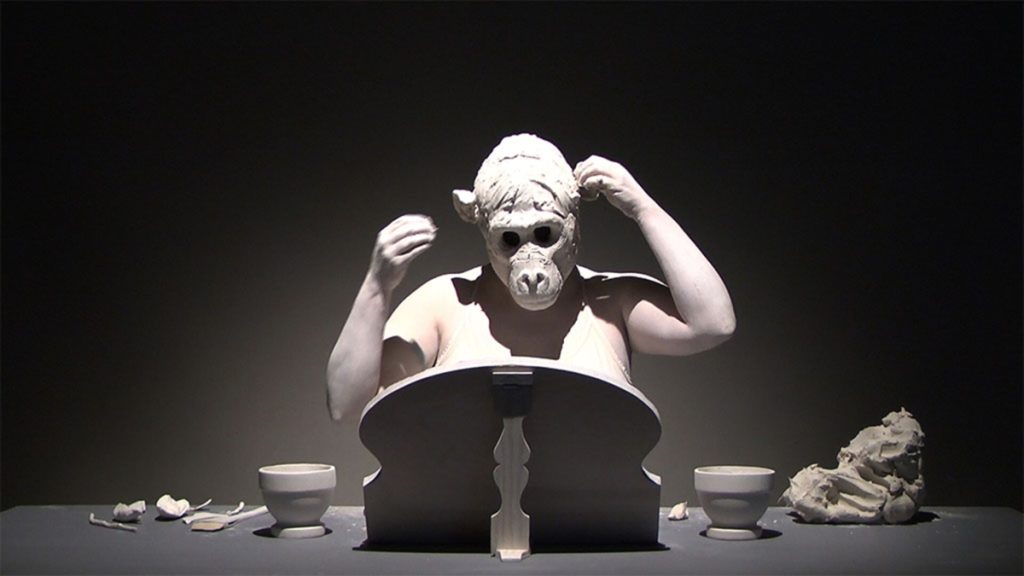

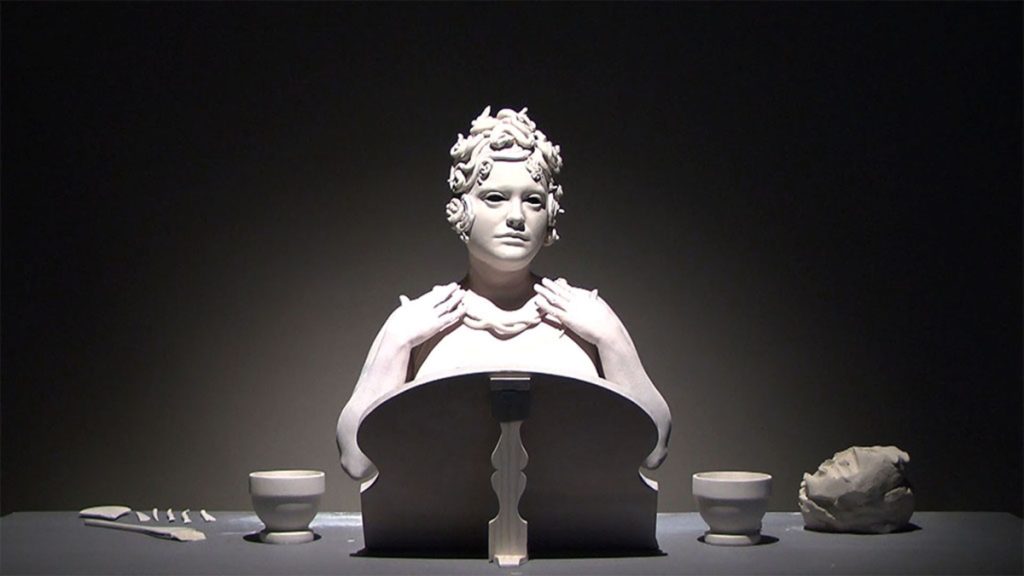

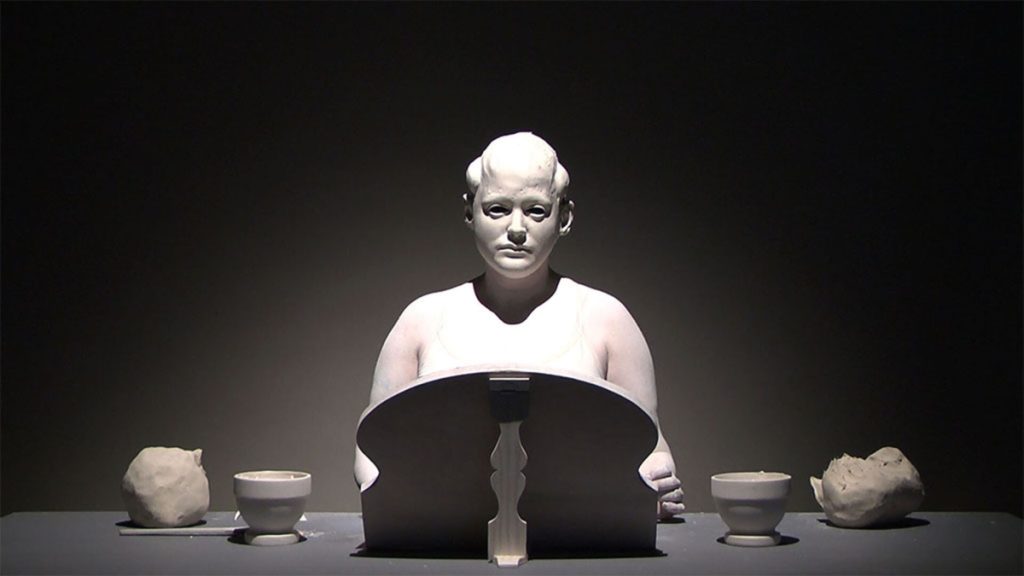

Wrangling with the beauty standards that society erects as the measure of a woman’s worth is the central issue of Teri Frame’s work, which becomes a performance through the creative process. The central issue of her work explores the construction of social hierarchies, particularly those of race, gender, aging, and ability. The sub-component within her work is researching human conceptions of beauty and their inextricable links to bodily hierarchies. Much like Cobbing, she too employs the prop of a clay mask, one that highlights certain attributes that Frame harnesses for her performance. Sitting before a mirror, she applies ever newer layers to her clay mask, constantly changing her appearance in the process. From instance to instance, her performative act can range from the broadly satyrical to the profoundly personal. The assumed forms tease various viewpoints on beauty standards and the associated problems, using objects that Western society understands and values as products that help achieve the norms we’ve set.

In its malleable state, clay is the perfect material for creating constantly changing depictions, a property so brilliantly put to good use in the animated pieces of the legendary Jan Švankmajer, who, in works such as Darkness, Light, Darkness (1989) and Factual Conversation (Dimensions of Dialogue) (1982) humorously models clay through the construction of a protagonist. We don’t often see clay as the star of such animated endeavors, as something more like play-dough is usually used, as it doesn’t dry out during manipulation. A constantly drying material undoubtedly complicates production processes that require smooth, clean, and consistent implementation, so it is much more appropriate to use in a different context.

Danijela Pivašević Tenner uses clay’s drying process as one of her primary means of expression, which facilitates her staging of sustainably oriented artistic practices in her creative process. Pouring liquid clay over everyday objects robs them of their primary function and questions the patterns by which objects are identified. At the same time, through the same act, she addresses the paradigm of understanding the identity of ceramics. Traditionally speaking, ceramics can only apply to something that has undergone firing. Pivašević Tenner, an artist with a major in fine arts in ceramics, transcends all traditional reference frames and boundaries in this regard. By doing so, she opens up the question of her own identity. This break from tradition is embodied by the cracks in the surfaces of the everyday objects that make up the entire piece.

Andy Goldsworthy is another artist who abandons the material to natural processes, both in natural settings (like with his work Clay Dome, 2012) and in galleries (such as for Clay Wall, 2007). The clay, along with all the other materials comprising a given work, is imprinted upon the space like a memory and is then left to be transformed by the new environment. Goldsworthy created the Clay Dome to forge the most intimate possible relationship with clay to truly understand its essence. The dome provided a meditative sanctuary, and the clay was left to the natural drying process.

The idea of constructing architectural objects out of clay is taken to another level by Nina Hole, whose work is an agile, multifaceted amalgamation of a range of artistic domains. The exhibited object undergoes a hybrid transition between something utilitarian (such as a stove) and something artistic (a statue), and the process in a specific location alongside the construction of a narrative is paramount to the performative nature of her work. Nina Hole attributes the clay object, usually a form of dwelling, to the role of a furnace. The whole structure of her work is subordinate to the directive that the resulting work plays both roles. This process is her guide from the foundation upwards to the ultimate construction of an insulating shell that allows a high temperature to be reached, thus changing the material. The shell is removed at the height of firing. We are, therefore, subject to a material that is in constant flux at the microscopic level.

Other artists have also identified the potential role that thermal treatment plays in transforming the medium’s status. The change in clay’s form as a product of thermal processing is where Christina Schou Christensen’s exploration begins, as her sculptures are a live testament to how the material moves during firing. Her technical expertise on various clays’ chemical properties, including their melting points and what sorts of clay mixtures can be made to manipulate those melting points, stretches the limits on what the material is capable of, and Christensen seeks out these extremes and playfully teases the shape of the vertical form. Christina Schou Christensen exploits how the material changes and becomes deformed in constructing her artwork’s very bases and fundaments. The technical knowledge that often justifies the characterization of ceramics as more trade than art is thus an inextricable part of the deeper process that provides the conceptual source of the whole. Thus, The cast’s structure becomes a frozen testament to the construction of the whole work and of the ensuing processes.

Just as the very structure of the constructed object allows Nina Hole to change an object’s identity, Cecil Kemperink similarly approaches the medium, molding her sculptures in the form of interconnected rings, allowing the viewer to constantly change the sculpture as we handle it, adding a new form to it. The work truly comes to life in her performative interactions with it. What was previously a static chain becomes an active vessel for sound. The sound released during motion becomes inextricable from the material itself.

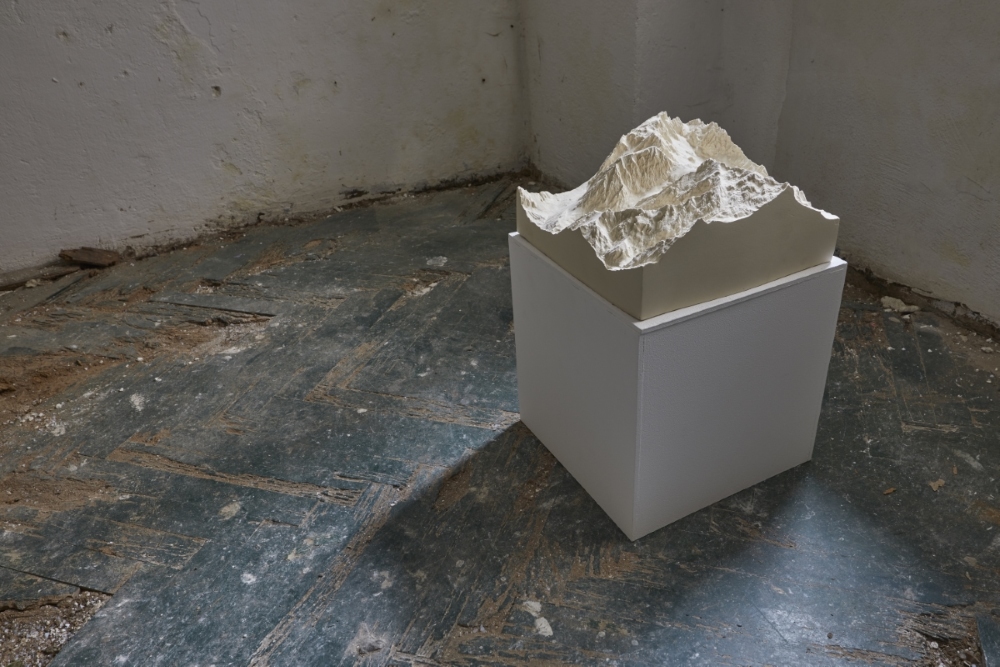

The wealth of varying practices and approaches that are found abroad are mirrored in Slovenian undertakings. A project at the Layer House in Kranj, πr squared, is an exhibition of contemporary kinetic ceramics, biennially showcasing the creative endeavors of established artists and budding talents, all of whom take an unexpected approach to handling the material. Their innovative projects gave Slovenian creation a welcome respite from the traditional depictions of ceramics, making viewers ride a wave of multisensory discovery. Špela Šedivy’s work Within Earshot (2023) produced a set of musical vessels that spin like dreidels, crumbling the traditional walls that confine the artistic relationship between viewer and viewed. Found shards in Louise Winter’s work hang vibrating in timelessness. That which seems a moment frozen in time at first glance transforms into clanging fragments that yearn to free themselves of their static imprisonment. Brigita Gantar and Meta Mramor designed their room-sized work Raz-bitje (2023) by placing visitors in the role of the piece’s co-creators. Destruction of the hanging clay orbs ensues as the result of walking through them, along with the crumbling of the clay bricks under your feet as you view the exhibit, and the piece reaches its climax with Meta Mramor’s performance, as she slices into a glass cast of her own body in order to topicalize body dysmorphia. Veronika Lah installs her dried clay structures outside and abandons them to the elements. Rain washes away layers of clay, which fall as droplets back to the earth in a return to that whence we all originate. In her piece, Third Report on Creation (2021), Lana Pastirk alludes to Jan Švankmajer. Impressions of faces set on a printing press, with parts of faces painstakingly arranged in the perfect spot, forget an intimate space where immortality can be sought by the artist. The human narcissistic mindset, along with the values and standards of modern society, form the central motif in Pastirk’s work. Nataša Ilec Kralj’s piece Inalienabilis (2021) marks an autobiographical contemplation on the concept of desire. Kamnik Saddle, a mountain pass in the Alps, constitutes the object-cause-desire relationship for the artist’s work. Deconstructing that desire is manifested in the repetitive casts of Kamnik Saddle, in which the artist manipulates the material such that each new iteration of casting causes the ultimate form to disintegrate into ruin. Ana Ščuka’s piece Cycle Ž (2021) sees liquid clay pumped in motion through PVC pipes that are bent in the shape of a microscopic clay particle. The driving force of life is the perfect analogy for the primary essence of clay, perhaps even that which Andy Goldsworthy seeks.

Before leaving, we should also highlight the exhibition cave_me (2021), a collaborative project between Timotej Rosc, Satya Pene, Ajda Rep, and Hana Tavčar. The Mahlerce Gallery houses the work, for which they combined textiles and clay to create a room-sized piece, an isolated space whose volume and material composition were set just so for the viewer to lose their orientation. The space is claustrophobic, but the combination of selected materials simultaneously produces feelings of comfort and coziness.

Kristina Rutar is an artist born in 1989 in Slovenia. She completed her studies in ceramics at the Faculty of Education, University in Ljubljana, in 2013. She continued her post-graduate studies in interdisciplinary printmaking at the E. Geppert ASP in Wroclaw, Poland. She mainly works in sculpting and ceramics, questioning the traditions of the two mediums. She received numerous awards and acknowledgments, and her works can be found in public and private collections. She lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia, where she works as an assistant professor of ceramics at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design.

Captions

- Caroline Tattersall, Spode towers, unfired bone china (Spode moulds), 2011. Photo credit: Darren Washington

- Alexandra Engelfriet, Skinned, installation and performance, 2018. Photo credit: Liedeke Kruk

- Marisa Finos, Vessel, 4-Day Durational Performance, Clay, Mirror, 2014. Photo Credit: Artist

Marisa Finos, Vessel III (with Harriotte), 5-Day Durational Performance, Clay, Sound, 2015. Photo Credit: Jenny Calivas - Teri Frame, Pre-human, Pos-human, Inhuman, Act I: Simians. Video Still, 2011

Teri Frame, Pre-human, Pos-human, Inhuman, Act III: Hybrids. Video Still, 2011

Teri Frame, Pre-human, Pos-human, Inhuman, Act VI: Post-humans. Video Still, 2011 - Danijela Pivašević Tenner, Do you know what’s behind, unfired clay and donated objects, 2018. Photo credit: Shine Bhola

Danijela Pivašević Tenner, Disposable Life, Performance, unfired porcelain, video work, 2022. Photo credit: Anna Katharina Rowedder - Cecil Kemperink, Big Rhythm. Photo Crefit: Marloes Coppes

- Christina Schou Christensen, Blue Legs, 30 x 30 x 40 cm, 2017. Photo credit: Dorthe Krogh

- Veronika Lah, Erosion, clay, steel wire, 2020/2021. Photo credit: Maša Pirc / Layerjeva hiša

- Ana Ščuka, Cycle Ž, pvc pipes, liquid clay, drive mechanism, 50 x 30 x 150 cm, 2021. Photo credit: Maša Pirc / Layerjeva hiša

- Lana Pastirk, Third Report on Creation, site-specific installation, plaster of paris, silicon, wax, hair, porcelain and stoneware, 2021. Photo credit: Maša Pirc / Layerjeva hiša

- Špela Šedivy, Within Earshot, terracotta and wood, 160 x 100 x 40 cm, 2021. Photo credit: Martin Peca

- Meta Mramor and Brigita Gantar, Raz-bitje, clay, photo, video, glass, 2023. Photo credit: Maša Pirc / Layerjeva hiša

- Louise Winter. Withouth title, ceramic roof tiles, string, site-specific installation, 2023. Photo credit: Maša Pirc / Layerjeva hiša

- Nataša Ilec Kralj, Inalienabilis, stoneware, site-specific installation, 2021. Photo credit: Davor Kralj