By Anne-Brit Soma Reienes and Per Ditlef Fredriksen

Who or what is the source of creativity when working with clay? In this essay we reflect on the outcomes of a collaboration between a ceramic artist engaging in performative pedagogy and an archaeologist working with contemporary material knowledges. Seeking a common conceptual ground, we explore the unruly outcomes of creativity in and through a series of selected ceramic works by Anne–Brit Soma Reienes.

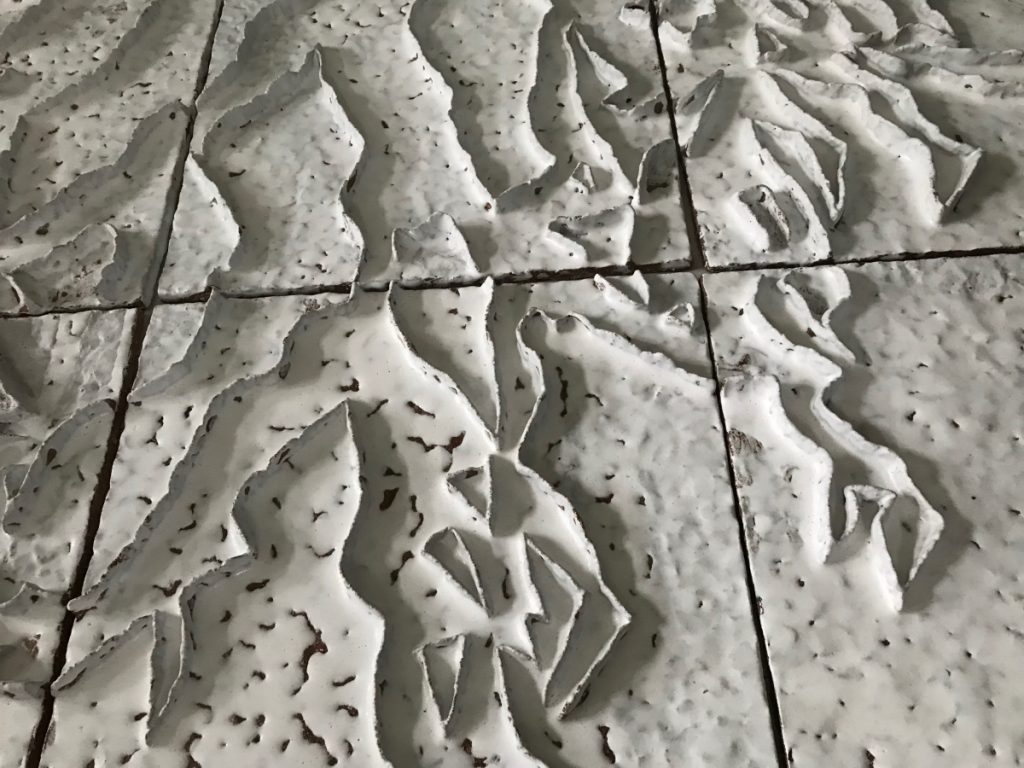

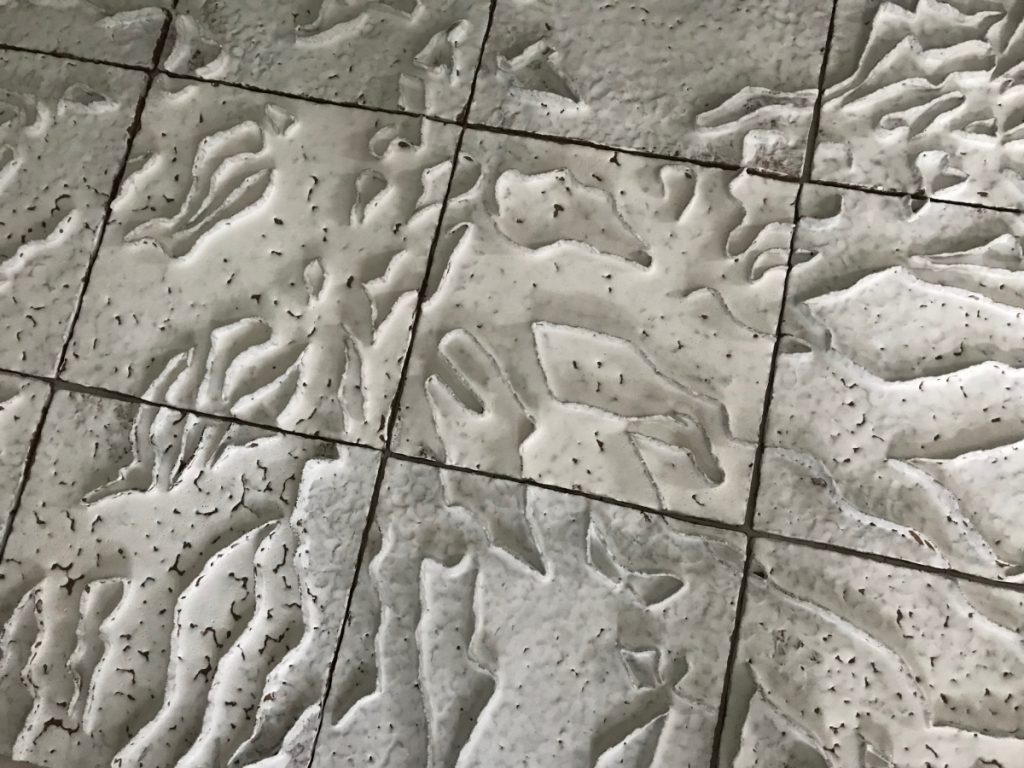

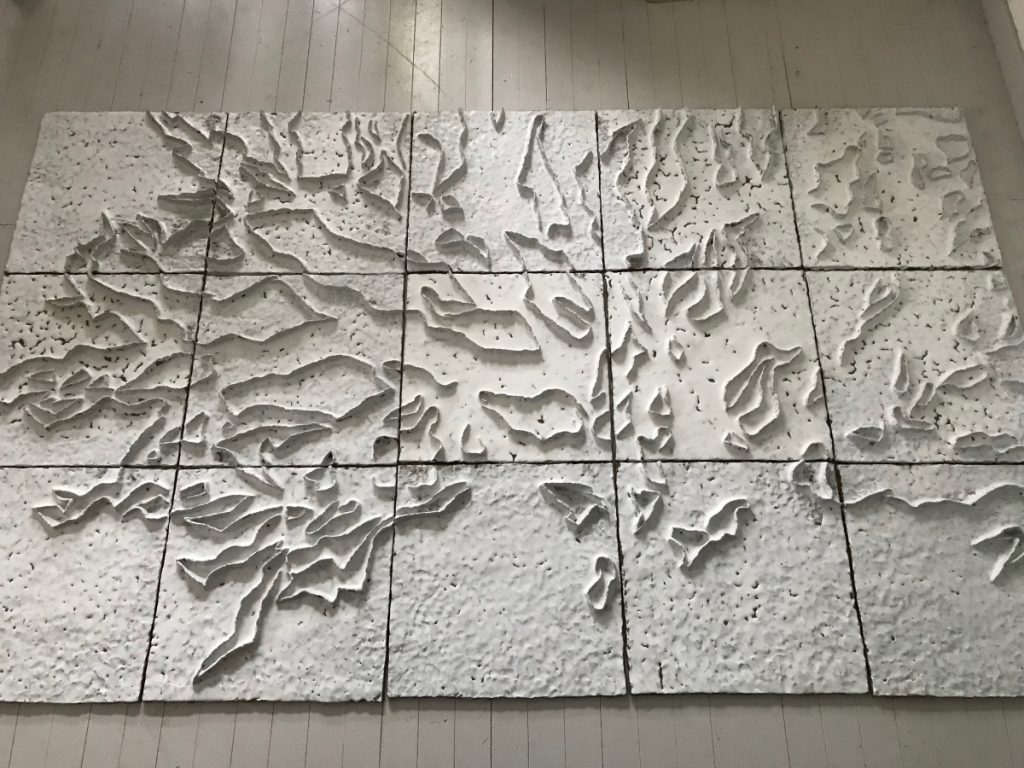

A key trait in several of Anne’s multi-component works is the growing and branching inwards from the fringes of seemingly disobedient organic elements, thereby disturbing the planned, systemic order at the perceived centre. The wall piece Under the Moon from 2021 (Figure 1 – featured image), consisting of 15 ceramic tiles, offers an illustrative example. The transformative movement caught while unfolding is a contrast and a looming threat to the neat order. Was there any order here in the first place? Or, alternatively, perhaps what enters from the outskirts are just elements of another form of order, one that is captured in a flicker of time while in the process of re–entering the world it has been expelled from? Is all this planned organisation just a snapshot of an abstract, externally floating idea that never really made it into our everyday lived–in worlds, a futile, short–lived exercise until something deeper and older reclaims its domain?

Curiously, this image also speaks to the creative process that brought Under the Moon into being. The meeting between movements and gestures of the human body and the clays’ material properties (Figure 2) propelled into an unruly growth of organic shapes and trajectories that extended beyond the spatial confinement of a singular tile, resulting in a multi–pieced assemblage. Anne’s own exhibition text sought to capture the act of making as resembling a moon-lit walk in the forest: a kind of stumbly wayfaring where the creative material process unfolds while thinking, reading and writing:

Perhaps everything revolves around the transition between body, perception, material, drawing and words. Seeking scripts and signs as fingers shape the clay. Writing forms. Sculpting surfaces. Crafting clay poetry. (…) Like wandering through the forest, under the moon, without ever arriving.

For us, the richly textured image of organic overflow across tiles, and our inquiries into the process of its coming into being, resonates with archaeologist Lambros Malafouris’ (2014) concept of creative ‘thinging’ and, more specifically, what he calls ‘the feeling of and for clay’. Significantly, for Malafouris, creativity is not the materialisation of some preformed idea. Rather than searching for external agents or constituents, we should approach the creative process of making as a dynamic interplay where “material and human agency are coupled with each other and allow action to gain a ‘life of its own’” (Malafouris 2014: 151).

Engaging with a small selection of Anne’s works from this perspective, the following text is the result of two researchers’ crossing paths. We come from different disciplinary backgrounds but share a long–term interest in ceramic arts and crafts. This includes a curiosity about the outcomes of bodily engagements with materials – in Anne’s case these materials are predominantly clay and driftwood. However, while Under the Moon and other works discussed here allude to unruly materiality and the temporality of artists’ bodily movements, there is also another key element for us pedagogues to take into account: the sociality of learning. That is, the fine-woven social fabric between makers and materials, between skilled teachers and learners and, not least, between performing artists. Our crossing of paths across disciplines results in a series of mutual, friendly interventions into our respective material knowledge and, thereby, also into how we approach materiality.

Under the Moon

For more than two decades, Anne has explored the hand-built tile as a medium for larger, multi-component ceramic displays. Under the Moon, which has been exhibited twice in Norway, is the most recent work made this way. Initially shown as the title piece in a solo exhibition in 2021, it also appeared the following year as part of the collaborative arts and crafts exhibition Persepsjon 2022.

The way of working can be traced back to when Anne moved from the urban centre of Oslo to a small village near the shores of Lake Mjøsa almost 25 years ago. This changed Anne’s ceramic expression in profound ways. The matte, white barium glaze originated as a way to perceive interior landscapes. The need to explore the dim whiteness of the inland light, which differs significantly from the sharper coastal light she had known from growing up in southwestern Norway and later living near the Oslo fiord, led to years of exploring various modes of glazing, eventually resulting in the particular glaze composition used to create Under the Moon.

A distinctly modelled order emerges as the assembly of tiles become interconnected by sculpted lines. This stimulates the perception of organic movement captured in static matter, the fired clay. The continuum expelled under the moon is an intended illusion, of arrested movement in a hostile yet soft landscape where nothing grows. This imagery draws inspiration from Norwegian author Torborg Nedreaas’ classic novel Nothing Grows by Moonlight (orig. 1947, English trans. 1987).

The tiles are all hand–built on a wooden plate, which then also defines their outer dimension. Bit by bit, clay is fed into and onto clay, slowly filling the spaces from the centre of the wooden plate and outwards, following the path of a spiral. This spiralling technique ensures stability and prevents the tile from bending or cracking in later stages of the ceramic process. A subtle, soft texture emerges from the traces of clay being pressed by fingers into and onto clay, thereby embedding the lines made on the surface in organic patterns that resemble moss branches (No. ‘reinlav’).

The resulting unruly lines, growing 1.5–2 cm out from the tile surface, offer the glaze separate square spaces to unfold within – and beyond. Poured over the bisque–fired tile while it is held up vertically, the various layers of glaze lead to either a slightly transparent or an opaque expression, and sometimes, in some smaller areas, the thicker layer of glaze ‘shrinks’ and reveal the red clay. The glaze and the textured surfaces intertwine. The white glaze holds its breathing body, supporting the lines, and it is up to the beholder to figure out whether the resulting textured image is of something that implodes or expands.

Reverberance

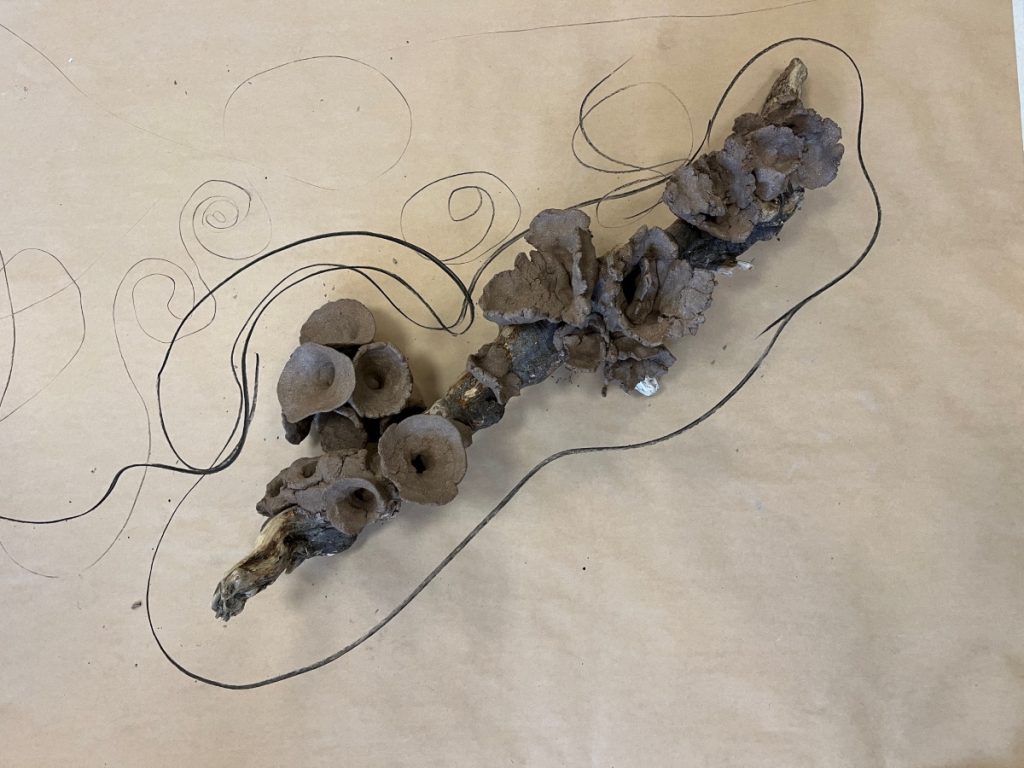

While sharing Under the Moon’s unruliness of lines becoming detached from the tile surface, the work with Reverberance (Figure 3) generated a new material expression for Anne’s multi-component assemblages. The barium glaze used gives it a novel expressive twist. Working on the piece during a stay at Kecskemet, Hungary, in 2020, resulted in the use of a local blue stoneware clay.

As in the case of Under the Moon, the work with Reverberance drew inspiration from anthropologist Tim Ingold’s (2018) notion of haptic perception. Here, visual perception is conceived as a correspondence of kinaesthetic awareness and material traces, rather than an optical projection of object to image. Reverberance consists of fragile and fragmented signs brought to life in a rapid manner, through pinching and bending of the clay. The small sculptures seek to capture intuition while unfolding. This momentary rapidness means that temporality is a key theme; the pieces evoke a sense of time flowing and the impermanence of life, the fragility of the human condition. The organic forms created in clay do not only seek to capture moments of growth and change; they also remind us of the fleeting nature of these moments.

These unruly mergings that make up Reverberance, fragile and out of place, are made in a relatively rapid series of movements. Interestingly, this work mode turned out effective in relating the concrete act of making in the immediate here–and–now to distant meaning and abstract symbolism. Beholders have so far offered a wide range of connotations and allusions to the work’s meaning, including shapes found at the water’s edge and in the forest (bones of fish, sheep or deer), affinities to cultures in circumpolar regions and Asia, and references to Italo Calvino’s postmodern novel Invisible Cities and various other utopian places and languages.

The ceramic hardness of Reverberance invites touching, evoking at one and the same time associations to the close and tangible and the distant unknown. It is like a skeleton, shared by many, but without the muscles and skin that help us identify and classify. Although inorganic, it looks and feels like a wing, a mythical figure, or even some form of ancient, ritual object.

Teaching future teachers: the sociality of learning

Reverberance also has another creative genealogy. The work’s coming–into–being not only refers to the relationship between the maker and the materials, but also the sociality of learning Anne experienced while working with children and clay. This kind of pedagogical long–term engagement has the potential to open up a field of playful possibilities fostering creativity. Moreover, Anne’s role in teaching future teachers to engage with kids and clay has led to further exploration of certain aspects of performative and embodied art.

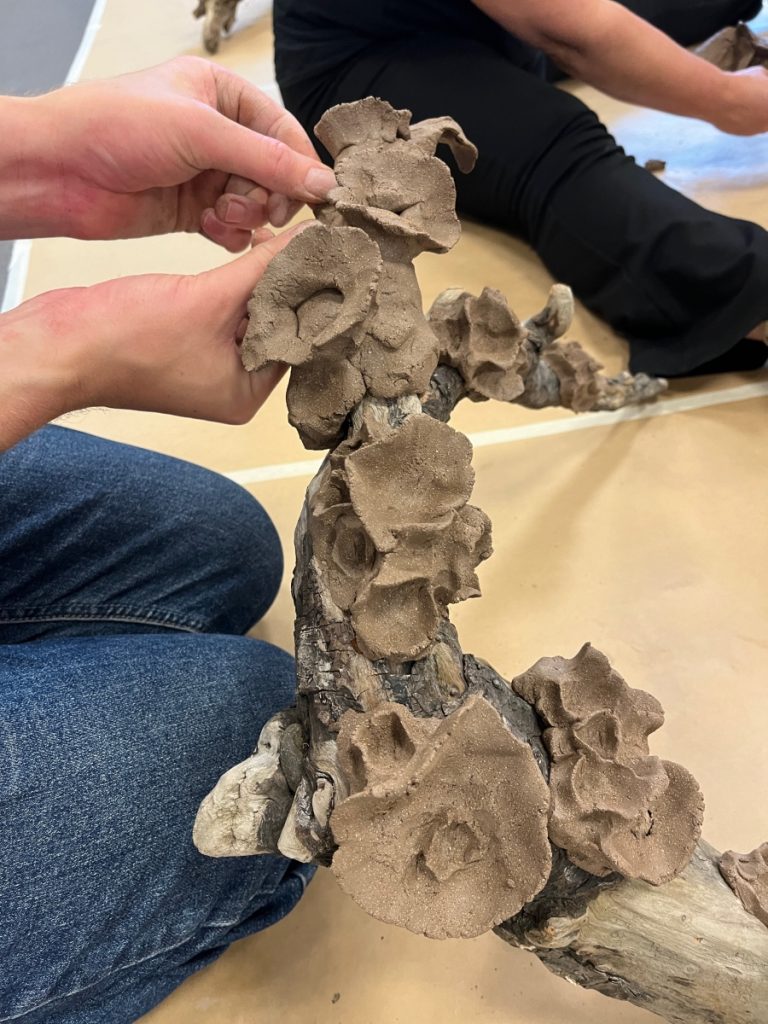

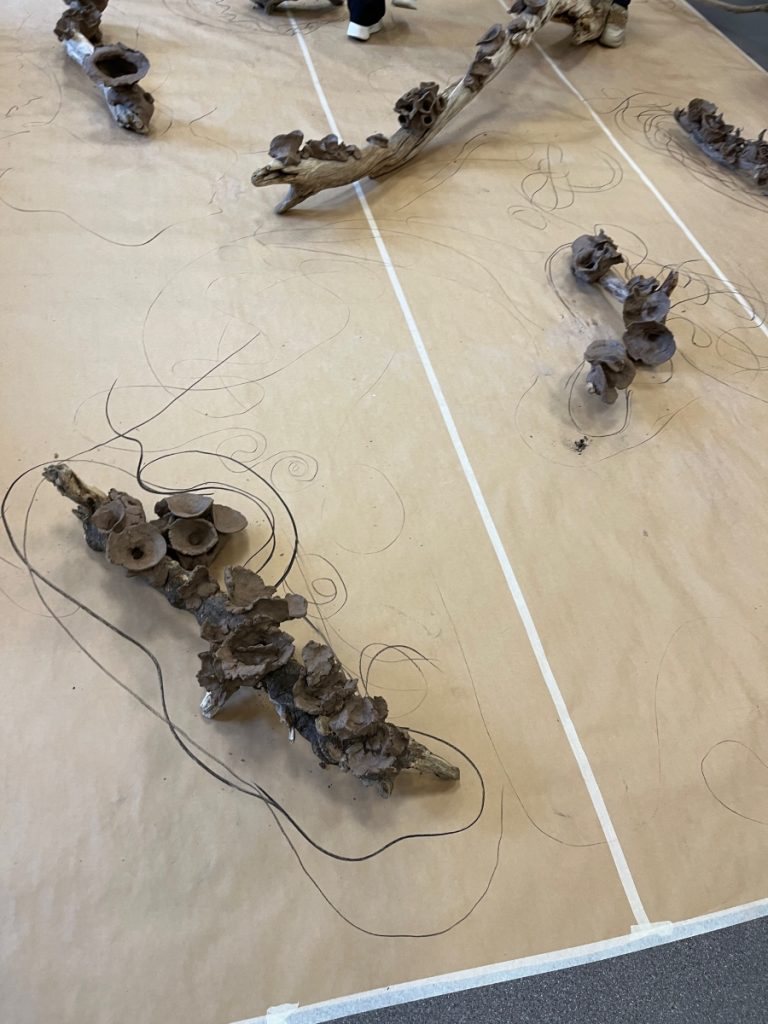

Collaborative work in the three–dimensional hand-building tradition, where intuitive expression interacts with the material agency of clay, allows students of pedagogy to gain material knowledge by sensing possibilities in the open-ended assignments (Figure 4). Most often, the collaborative work takes place on the floor while listening to music, thus allowing for movement to beats and sounds while working. Conducting a process-based project with students engaged in performative use of clay invites an intra-active mode of engaging with the material (sensu Barad 2007). This work mode requires focus, immersion and presence in the here–and–now. In this manner, the mergings of material and human agency are given open and free places to unfold.

Among the insights the students gain in this performative growth assignment is to discover form-while-making. The idea is to build from an inner space and not around it, thereby allowing the individual qualities of surfaces, edges, constructions, details, and whole forms to develop. This performative assignment was given to a group of 23 students in a classroom where the floor was prepared with a display of driftwood (Figure 5). What happens when transformative, malleable, wet clay merges with dry and unruly driftwood? Inspired by the works of Caroline Kirksæther (as discussed in Kvalbein & Reienes 2024: 103–50) and Alexandra Engelfriet, the students were instructed not to communicate verbally, only through actions with the materials, the premises of the hand, the clay, the room, the classmates, and the participating teachers. The idea was that such meetings with unruly, transformative clay and dry, organic driftwood, however brief they may be, has the potential to reveal a perceptual, bodily understanding of form.

Fingers were pressed into a lump of clay, creating tiny spaces that invited extensions. To the sound of soft electronic music, forms grew like shapes in the forest or on the ocean floor. This dynamic learning process, where ideas and insights were continuously exchanged and explored, became a practical, physical dialogue between all participants. This multimodal field was a safe space for improvisation and facilitated material encounters, thus allowing performative processes to unfold. In this manner, learning happened through dynamic interaction between the student and their material and social environment.

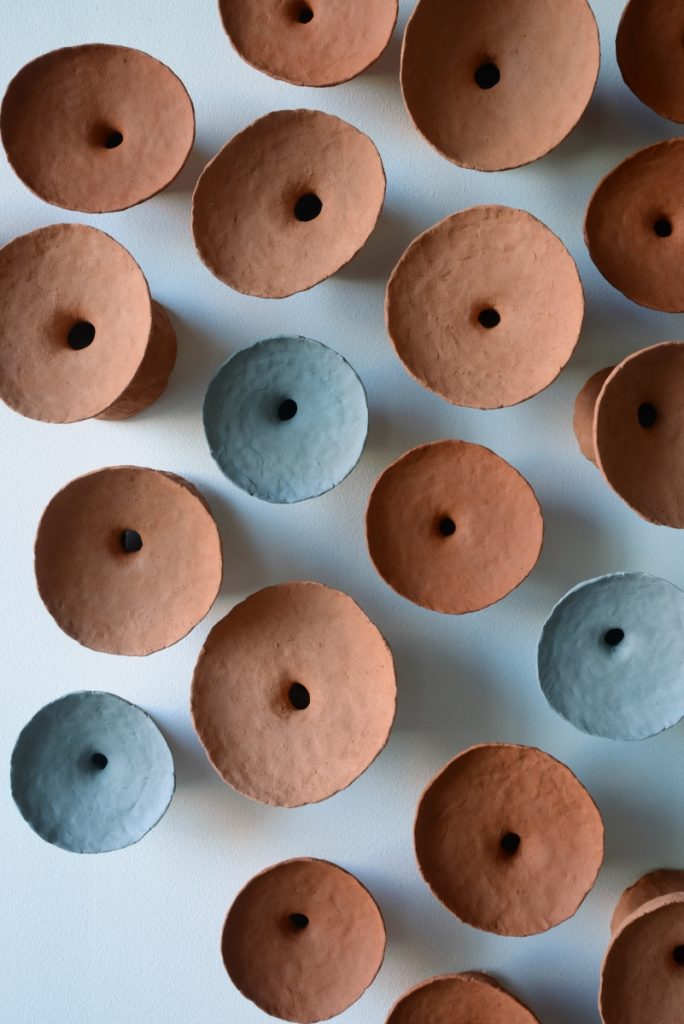

Syncopes

The work Syncopes is an assembly of 31 orange-red and graphite-grey concave shapes mounted on a white gallery wall (Figure 6). The very texture of this piece is made up of the raw, unglazed and low-fired shapes, the bare traces of fingertips pushed into chamotted clay. The tiny shapes resemble space antennas, which seem to spin while searching for signal, either for receiving or sending. The rim of each of the hand-built clay shapes is bent slightly upwards, which gives the impression of a functionally added line to prevent or stop further movement outwards. The rim itself has a rounded shape, encircling a dark and open throat – a hole where the bottom is not visible – located slightly off-centre. At the bottom of the hole, close to the wall and hidden from public view, is a piece of black velvet that undergirds and reinforces the sense of depth – and the looming darkness of this depth.

While Syncopes explores movement in minor, subtle ways that relates it to Under the Moon and Reverberance, this particular assemblage also opens up for novel inquires, in particular the suggested connotations to written and spoken words. To build a form that fits inside the hands from start to finish gave a sense of comfort, but it also brought Anne out of her own comfort zone as a ceramic artist. The work mode was different from earlier, thereby challenging her established habit of working on larger scales. The small clay shapes were made in hand, close to the body, emerging from the experience of reading poetry, listening to music and singing while working. In other words, the disjuncture of habits and the scaling down offered a change of pace and rhythm, resulting in a multi-component assemblage that expresses the importance of looking off-center for meaning and meaningful intimacy: to draw closer to really see and listen what is done and said by others.

A performative workshop

Several key aspects explored above were played out in interesting ways in a performative workshop staged in an old theatre from 1927 in Hamar, Norway, in September 2024. The installation formed a stage, an inviting framework, which brought together clay and driftwood, the latter collected at the nearby shores of Lake Mjøsa, bodies and acoustic sounds of voices and instruments (Figure 7).

The participants were students and colleagues. Each participant found their own space within the installation. Sitting with eyes closed and receiving a lump of clay, they were told to explore the clay by holding, pulling, pushing, and pinching the clay. From the room next door, music from a piano softly spread and blended unfamiliar, improvised soundscapes into the atmosphere, subtly resonating with the rich stories of the theatre building seeping out of the walls. The light-flooded generously into the room. The wind presses in from the lakeshore, literally singing through the tiny crack of the balcony door. The participants moved slightly differently as the piano sounds changed in tone and rhythm. The room was tuned in, inviting concentrated listening and exploration.

As the soundscape expanded by adding the tones of a muted trumpet, the partakers became more exploratory. Branches and bodies intertwined with the clay. Pinched clay-filled cracks; clay sheets stretched from twig to twig. In this manner, the driftwood became a composed score spread out on the floor, with organic variations in size, weight, height, width, and length. The worn and polished driftwood has its own frequency and character: light silverish grey with graphic patterns, stripes, lines, arches, and curves. Sharp and blunt shapes. Whirling branches and trunks that twist. Bone-dry bark and unruly roots spin entangled together and out into the air. At one and the same time, the driftwood both resembles and not resembles something familiar, being deprived of earth, water, light, and growth. It serves as a springboard for imaginations and sensations, a trigger for new stories.

The clay became unruly shapes glued to the dry driftwood, slowly giving up its water content, sinking into the wood. In a short period of time, the transformative material allowed each individual to create something unique, something unseen that, to borrow Malafouris’ phrase, gained a life of its own. The engagements with materials opened a new path. New performative connections were made with materiality in motion.

A crossing of paths and its outcomes

An outcome of our joint venture into Anne’s creative processes is the unforeseen merging of two analytical domains. On the one hand, there is the temporality of making. As we have seen, changes of bodily pace and rhythm may not only result in different work modes and their flows, but it may also even change the scale of the works themselves. On the other hand, there is the sociality of learning, the very co-creation of meaning resulting from the bodily absorption of inspiration from the artist’s immediate surroundings. This undergirds the importance of paying attention to the intimacy between body and materials. Indeed, it only makes sense, as pointed out by Malafouris (2014: 152), “to think of process and flow and ask questions about what the clay and human hand can do when acting together, in partnership”.

The genealogy of creativity behind Anne’s hand–built tiles reveals the deep connections between subtle-textured surfaces, and the lines emerging from them, and the emerging forms in which these surfaces and lines grow and expand in unruly ways. Moreover, as seen for Syncopes, an outcome of a disturbance or disjuncture in an artist’s established, routinized engagements with clay may cause changes to form and scale. This leads to a new set of questions, which we leave open for future exploration:

What is the role of such interventions and disturbances in the creative process?

Sources of inspiration

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ingold, T. 2018. Touchlines: Manual inscription and haptic perception. In Johannessen, C.M. & van Leeuwen, T. (eds.) The Materiality of Writing: A Trace-Making Perspective, 30–45. London: Routledge.

- Kvalbein, Å. & Reienes, A.B.S. 2024. Leire og keramikk. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget.

- Malafouris, L. 2014. Creative thinging. The feeling of and for clay. Pragmatics and Cognition 22(1): 140–158.

- Nedreaas, T. 1987 [1947]. Nothing Grows by Moonlight. London: Penguin Random House.

Anne–Brit Soma Reienes has an MA degree from the Ceramic Institute at Bergen Academy of Art and Design, Norway (1988) and an MA in crafts from the Hungarian State Academy in Budapest (1993). Reienes has participated in several exhibitions in Norway and internationally and has made installations for public as well as private clients. She works transdisciplinary and performatively with text, drawing and materials, and has previously also created installations in public outdoor spaces using brick and granite. Reienes is currently employed as an Associate Professor at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Inland, Norway, and is a member of the International Ceramic Academy in Geneva. Reienes works with clay sculpturally and two-dimensionally and contributes to the ceramic field by publishing books, chapters and articles. Among her latest contributions is a handbook on clay and ceramics (in Norwegian) co-authored with Åse Kvalbein, published in 2024.

Per Ditlef Fredriksen has a Cand. Philol. (2002) and a PhD (2009) in archaeology from the University of Bergen, and he is currently a Professor of Archaeology at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo, Norway. Fredriksen is the leader and PI of the research project ARCREATE. An Archaeology of Creative Knowledge in Turbulent Times (2023–28). His key interests are craft knowledge, learning and creativity, human–thing relations, meetings between knowledge systems and ontologies, memory studies and translocality. He works within the fields of contemporary, historical and prehistorical archaeology and critical heritage studies. His interest in contemporary archaeology extends into anthropology and environmental humanities. The engagement with arts and crafts has led to collaborations with artisans and artists in Norway, South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Zambia.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Featured image

- Figure 1. Anne–Brit Soma Reienes, Under the moon, 2021, stoneware-clay, glaze, 129 x 214 cm. Photo by Julie Tørrisen