Kyle Scott Lee: Patternmaster

By Susannah Israel

When I saw Kyle Scott Lee’s black and white ceramic cups brushed with vivid color, I thought of techno mudcloth. Our minds get a kind of one-two punch from seeing familiar and unfamiliar stimuli at the same time. My response was to get myself a cup; it’s on the desk as I write. Thus foregrounded in my day, Kyle’s cup led me to examine and review his remarkable work. Dave Hickey calls that one-two punch “Huh?/wow!” because art should make the viewer look closely. “Huh?/wow!” he explains, provides “that visual jolt of unfamiliarity that is prelude to delight.”

Kyle came to New York to be a painter, and he succeeded mightily. After taking a pottery class, he directed his intentions to painting pots. He financed the move to Brooklyn and established his studio while working in IT (computer information technology) as a change manager. A change manager, says Kyle, plans across multiple processes, reviews and balances these changes, and helps people use and adapt to the new. I find this germane to the artist: changing his life, learning new methods and technology, and applying them to create original ceramic art.

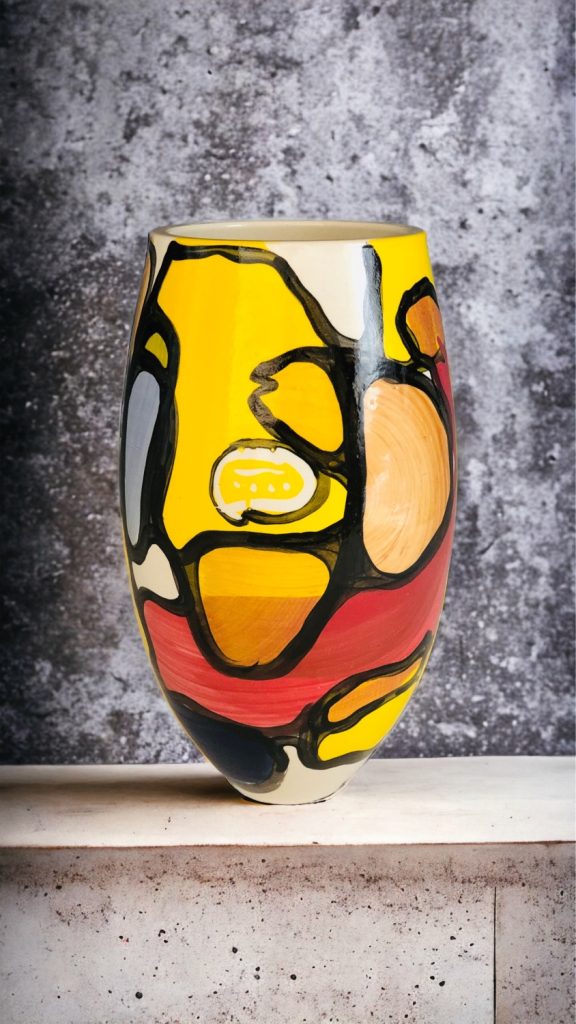

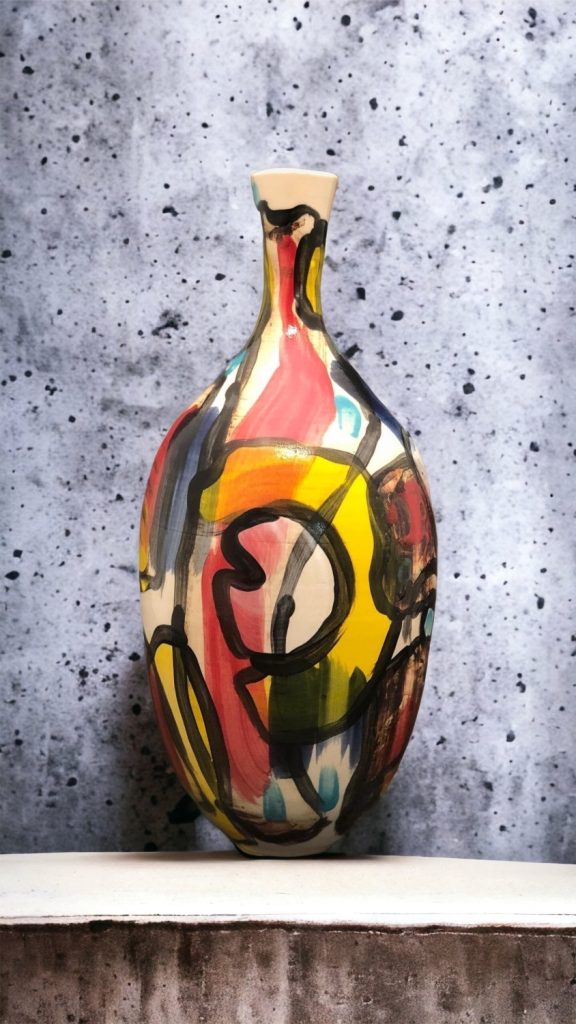

Asked about influences, art history, and theory, Kyle doesn’t cite American studio ceramics. His cup, platter, vase and bowl forms provide elegant surfaces for a wide range of evolving ideas. Where I see Yayoi jars, he sees shaped canvases for his brilliant, dynamic paintings. He recently made a series of pieces inspired by the pattern-in-a-square of Chuck Close. He mentions the influences of Basquiat and Mondrian, but also see Ettore Sottsass’ elegant designs and the Miro/Artigas collaborations: echoes of Joan Miro are present in his freehand brushwork, where blocks of strong color are outlined in black as they move around the form.

This is a 21st-century artist at work. Kyle’s art education has been his own diligent art practice. American ceramic artists who went to art school share a common knowledge of precepts, persons and history which doesn’t influence Lee. He considers himself self-taught in ceramics, after taking a community class to learn technique and set up a studio. This is less and less unusual. There are many paths to the ceramic arts, from the college degree and its fine art association to direct apprenticeship and many kinds of cultural practices. Cost and accessibility have certainly made the college path harder, while improvements in recognition, representation and resources have been a positive change for those historically denied access. What is evident is that no matter the introduction to learning, it is by making the work that we learn. It’s a lifetime journey.

Kyle Scott Lee and I both grew up on the East Coast of the United States when the colonial framework was imploding worldwide. Yet cultural appropriation continued to be an insidious problem. In the 21st century, we are seeing more recognition of artists throughout the African Diaspora. African American artists have deep roots in ceramic history. Previously, lack of opportunities to teach, practice and sell artwork limited Black ceramicists being recognized now. An important part of the community for Black ceramic artists is conscious support of one another’s work, forming groups, holding events, creating art centers, and teaching.

Kyle Scott Lee does all of these. Community is fundamental in his practice, which includes curating, exhibiting, organizing and attending community art events. He cofounded Gasworks, where he continues to teach a weekly class, He serves on the Board of the Kaabo Clay Collective of Black ceramic artists. Kyle was also artist in residence at Watershed, where he began to use a vinyl cutter for his painted designs. He says of his last, intensive, hand worked vase, “That’s the last one I’ll ever do this way. I just can’t paint another ten thousand circles by hand.” This gave him further scope in his designs, of which my favorite is his sumi-ink brushed circles that expand the intricacy and relationships of form that began with dots.

The “visual jolt” Kyle’s work delivers certainly brings delight. Color and design are what the work is all about, he says. The intense color and the profusion of repeating designs brings to mind the Pattern & Decoration movement. In a 2020 interview with David Ebony, curator Anna Katz states that P&D was considered bold, flashy, and promiscuous. Why promiscuous? Because pattern is not specific to any medium or material, it was not considered “high art,” confronting the racial bias of historical categories and value systems of Western art. The Pattern & Decoration movement helped set in motion an important contemporary change in ceramic art practice. This is integral to the energy and freedom of Kyle Scott Lee’s studio work. It is not necessary to have a degree in color theory to create a painting, as Kyle’s color sense makes clear. Ceramics rewards patience and the ability to learn from mistakes as well as success. Kyle’s painterly surfaces begin with priming the forms like a canvas. Next layers of color are fused in the kiln before receiving intricate patterns and a final glaze firing. His brushwork, resist techniques and airbrush make each piece unique.

Kyle Scott Lee’s distinctive work has received much critical attention. He’s a prodigious workhorse with recent exhibitions at Radius Gallery, Companion Gallery and Bergdorf Goodman. The NY Historical Society chose Kyle for the Commeraw Commission, Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw. Born enslaved, Commeraw rose to prominence as a free Black entrepreneur, owning and operating a successful pottery. For the commission, Kyle transformed Commeraw’s 17th-century designs into elegant borders for the 21st-century forms he created. Currently Kyle is making work for the second annual Cookout, a wood firing at the Hambidge Center focusing on Black ceramic artists. He’s pursuing the challenge of vivid reds and yellows so elusive in wood-firing practice. I look forward to his results.

June 2024

Read more about Susannah Israel and discover her work in Ceramics Now.

Visit Susannah Israel’s website and Instagram page.

Comments 1