Marieke Pauwels: Prima Materia, 2004-2021

The master says:

Dao De Jing, ch25

“ Elusive! Vague! Pictures in the middle! Vague!

Elusive! At the core are things!”

The creative process leads artists – me, anyway – to existential questions. At first, I found the folkloric devotional practices of the Low Countries inspiring. Gradually I started to take an interest in Eastern cultures. Once I started visiting Asia, I became more intrigued than ever by Eastern philosophies. For some time now, I have been exploring such themes as chaos and order, form and emptiness, matter and energy.

Across time and space, man has pondered the incessantly shifting substance or matter that surrounds him. Such reflection forms a starting point for my investigations – as revealed in my works pertaining to landscapes: mountains, scholars’ rocks and bivalves. This investigation of matter inexorably had me scrutinizing the intimate relationship between chaos and order, for the very process of creation demands a return to chaos, while simultaneously drawing me into the orbit of emptiness.

EMPTINESS

Without emptiness, it is not possible to create something new. First there is the raw earth and the artist. Both are empty in a certain way. “Because form is emptiness, form is possible. (…) Emptiness means empty of a separate self. It is full of everything, full of life.” (Nhat Hanh, 26).

We are referring to two notions. Firstly, emptiness is full of everything that exists around it and helps shape it. Secondly, emptiness is a condition for fullness. Without fullness there is no void and vice versa.

This emptiness, transcending its erotic aspect, also implies thinking from the body, dimming cerebral reflection. The body thinks for itself, relies on sensing in the now, and thus, on the body knowledge that has been accrued through practice, and so knows what it is doing. Body thinking is the catalyst for my method in giving erotic power to my works. To act with this embodied knowledge we must create a void, an absence of all incidental and external factors. We embrace spontaneity, coincidence, wuwei, the unexpected. Emptiness as a non-method.

Meanwhile, trying hard to achieve emptiness, ironically, my work often seems Baroque and packed. In a sense this resembles the fussy fullness of Baroque music, with all its ornamentation which embodies an otherwise unthinkable brimming emptiness.

LANDSCAPE

Landscape, particularly mountains, form an enduring source of inspiration. Moreover, it is fair to say, that my landscapes, including my erotic landscapes, reflect my own inner landscape.

In these art forms, I occasionally leave my clay unfired, thereby granting a work its own ‘being’ as well as a pregnant chaotic emptiness, a promising light-space. In La Petite Mort de Kunlun, more than three tons of unfired clay allowed my body-thinking free rein. Matter remains matter, clay resolving to the form of a mountain.

Clay is earth, and like earth it blends itself into its own shape. Meanwhile the landscape laid out in clay, acts as a metaphor for the chaos, bringing forth the world – simultaneously multiple and void.

In Parnassus (2006), a somewhat older work, I placed a mountain of unfired – and therefore free, unrestrained, not yet stone – clay on a revolving turntable. The resulting work revealed the mountain as a mighty hurdle, a result of the solidification process, but now in motion on the turntable as the observer enters the space, thus challenging the perspective of the viewer.

I was raised a ceramicist and acquired ceramic skills from early childhood. So, naturally, I also work with classic fired clay, a medium where the alchemy of the glazes forms a counterbalance to unfired matter. Take my ‘Scholar’s Rocks’ (2020) (or Gongshi as they are called in China) for example. Gongshi, refers to stones which are considered sacred, set up as a kind of spiritual guardians, usually in a pot or on a pedestal. In my contemporary interpretation, I often use space as a pedestal for the stones. These stones can truly be compared to mountains. They represent the same chaos, earth and spiritual energy. As such, I find that stones are apt to challenge the dualism between figuration and abstraction. Moreover, let me note, that I will occasionally introduce an actual figure (see Kwanyin-Kwanyin e.g.) as an element in the landscape – humble or noble, spiritual and/or erotic.

In my erotic landscapes Eros (love, lust) and Thanatos (death) are inextricably linked.

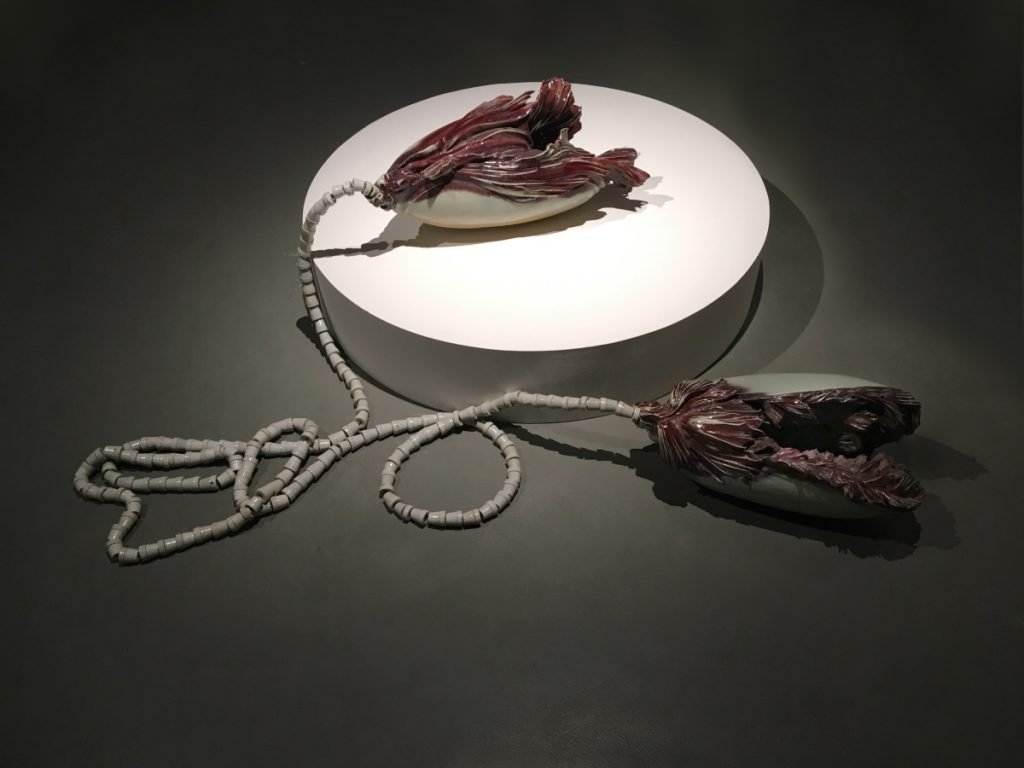

Originally, I focused on the ellipse as a symbol of emptiness – a perfect balance between two opposite foci, which coexist, not in a radical dualism, but rather in a valuable interaction within a unity. More recently, I have been exploring the formal value of the ellipse as an erotic form (abstraction of a vulva, as frequently found throughout art history). Sculptures, such as Bivalvia (several works have this title, 2020) and Lust (2012), admittedly take the form of a mussel shell, rather than a pure ellipse, so reinforcing the association with the female gender. Pure body and pure tangible, malleable matter are in play.

Displaying my work at an exhibition also ties into the notion of landscape. In earlier shows I PERFORMED with and indeed without clay. As for now, I consider each distinct piece a per-form-ance. I revel in the act of setting it all up as I move through the form and space, by way of my body-thinking, balancing the installation until the juxtaposition of lone pieces and separate sections within the room, reinvent the landscape and unveil more intricate connections and a deeper meaning. In the same way, I hope and expect that the viewer accepts my invitation to become a participant.

TWO VISIONS

In ‘Two Ways of Looking at Ceramics’, James Elkins tells us, that to be involved with ceramics means: to be on the one hand passionate about fundamental philosophical concepts such as matter, thing, utility, and on the other hand to be attentive to sensual, non-conceptual action, implying touch, colour, feeling, and temperature.

I for one, have the profound conviction that this double outlook makes for works of great strength and enticing charm. Indeed, I am very much aware that my own strongest works appear when I succeed in combining a philosophical and a physically sensitive approach to the matter.

+

Kwanyin-Kwanyin communicates space from dual characteristics: on the one hand the erotic aspect, which stands for feminine receptivity, on the other hand the religious aspect, which is portrayed in a pouring gesture, representing pure surrender.

It stands for an open free mind, which frames an endless space. An invisible and immaterial spirit – originally inspired and represented by the Eastern Goddess of Charity Kwan-Yin, confirms the ultimate moment when this freed spirit evaporates into unfathomable space. The Goddess Kwan-Yin tells us: “Everything returns unto the void”.

These relics derive from teeth. Traditionally our people offered wax teeth in devotion because they believed this offering would relieve toothache. I confronted this phenomenon with the essence of the artist, who, using material, aspires to transcend material. I researched forgotten rituals in the folklore of diverse peoples, questioned rationality versus irrationality, the abstract versus the material, … In each culture I encountered stories and legends in which teeth have a special meaning.

The ceramic teeth I originally created have since evolved to resemble the shapes of bones. I worked the noble porcelain with an unusually rough and primitive approach. To me this does nothing to degrade this noble and elevated material. My work can no longer be regarded as teeth or bones, but has become a discovery of a relic. My concept is one of many more bones heaped up … as a ritual, indeed, as a potential offering.

The cluttered disorder of my studio was the original starting point for Abanico/Cast 1. In my later research I hope to be able to confirm that this practical disorder is related to the chaos in the cosmos.

Todo es abanico: cual es el punto Céntrico? is a work through which I attempted to archive my studio stuff. I tried to archive it in horizontal layers of Emptiness, Materials, Energy, Final form, Waste. Vertically I tried to order the themes Landscape, Eros & Thanatos, Myths & Religion.

I soon noticed I could not put certain things in the right box/place: a piece of waste becomes my work, or my work becomes material … In the end I prefer to leave room for change and development, not creating rigid strata. I want to play and to keep connected things moving.

Photo captions:

- La petite Mort de Kunlun, 2019-2021, Chinese porcelain and loam, 400 x 250, © We Document Art

- La petite Mort de Kunlun – detail

- La petite Mort de Kunlun – detail

- Expo Das Spiel der Najaden – overview, @ We Document Art

- Das Spiel der Najaden (after Arnold Böcklin), 2021, stoneware – wood – metal bars, box: 120 x 160 x 135 – total: 350 x 420 x 320, © We Document Art

- Das Spiel der Najaden (after Arnold Böcklin), setup research EKWC, 100 x 156 x 120

- Prima Materia, 2012, installation: glazed porcelain – styrofoam – dry clay, 420 x 680 x 460, © Wim Wauman

- Scholar Rock, 2017, installation: stoneware – metal – plastic, size depending on the space – rock: 100 x 65

- Scholar Rock, 2017

- Space Grains, 2018, porcelain and stoneware, 32 x 19 x 21, © Boud Cielen

- Scholar Rock Formation, 2017, porcelain – wood, 26 x 17 x 20, © Boud Cielen

- Parnassus, 2006, installation: unfired clay – potterswheel – wallpaper and poster – the mountain starts to run when someone enters, size depending on the space – wallpaper length: 6m

- Bivalvia – Lust, 2019, stoneware, length 120 cm, © Miles Fischler

- Expo Das Spiel der Najaden – overview Bivalvia, © We Document Art

- Ellips, 2019, stoneware, 120 x 60 x 25, © We Document Art

- Bivalvia – Co-existence #1, stoneware – porcelain – wood, total installation: 200 x 160 x 50 – one shape: 50 cm

- Bivalvia – Co-existence #2, stoneware – metal – porcelain pearls, 110 x 80

- Cabernet Sauvignon #1, 2015, porcelain, 70 x 30 x 15

- Cabernet Sauvignon #2, 2015, porcelain and chalk, 120 x 100 x 30

- Kwanyin-Kwanyin, 2015, porcelain, 138 x 60 x 36, © Peter Cox

- Yellow Intervention, 2020, porcelain, 18 x 13 x 24, © We Document Art

- Relics & Apollonia, 2004-2007, Westerwaldprize 2009 – exploration in popular piety, porcelain and plaster, size depending on the space – 1 bone: 120 cm

- Abanico/cast 1, 2014, installation – various materials, 220 x 200 x 160, © Kurt De Wit