Ozioma Onuzulike: Dotted Lines, 2023

Essay by Ngozi-Omeje Ezema

Over the years, ceramics have transcended through generations, changing styles, functions, and structures. Closer observation revealed these changes occurring in the Nsukka art school after the assimilation of Uli and Nsibidi designs. H.C. Ngumah opined that ‘with the formalization of ‘uli’ design as an artistic language of expression in the Nsukka art department of the University of Nigeria, the production of ceramic wares features profuse use of linearity in a variety of manner.’1

Uli design is a body and wall painting crafted and executed by the female folks in Igbo land. Subsequently, uli design, an indigenous idea in combination with Western art, evolved into a “natural synthesis” philosophy propagated by Uche Okeke and the other Zarianism. Zarianism is used to refer to the founding members of the Zaria Art Society, established in 1958. According to Don Akatakpg, ‘Yusuf Grillo, Simon Olaosebikan, Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Demas Nwoko, Oseloka Osadebe, Okechukwu Odita, Felix Ekeada, Ogbonnaya Nwagbara and Ikpomwosa Omagie are the founding members.’2 These artists started the movement that embraced the indigenous culture and art making, reflecting their origins rather than imbibing the European Western style of art curriculum. This movement was the genesis of modern Nigerian art. Among those cultural styles and art making are uli designs from the Southeastern region of Nigeria. Uli is best known for its linear style and dotted designs. Many contemporary Nigerian artists, particularly those from the eastern part of Nigeria and other tribes who resided within the eastern region during the inception of uli, have experimented with, explored, and used uli designs in many art genres. Uche Okeke, El Anatsui, Chike Aniakor, Obiora Udechukwu, Tayo Adenaike, Chris Echeta, and Ozioma Onuzulike have explored this design in diverse forms.

Ozioma Onuzulike, among the artists above, is one of the recent generations of artists who have experimented with uli linear designs and has taken his explorative tendencies a notch higher. In 1972, Onuzulike was born in Achi, near a pottery community called Inyi. Besides growing up in close proximity to a pottery community, he was exposed to domestic chores that inspired and added to his creative prowess in ceramics. Thus, the observed domestic activities, the palette from which he drew his early inspirations, were the repeated lyrical lines created with broomsticks while sweeping the sandy courtyard, lines of razor blades on peeled oranges, and the ‘Abacha’ (African cassava salad) technique of peeling fresh cassava tubers. Hence, it was not surprising that Onuzulike was captivated by the recognition of the similarities to his mother’s knife strokes when he enrolled at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1992, where the dance of lyrical lines of uli was very prominent at the time.

The renowned artist El Anatsui’s wood works, carved lines by Chijioke Onuora (a multi-talented artist), and lyrical poetic lines/brush strokes of Chike Aniakor (a painter and a professor of African art history) further incited his imagination. Onuzulike stated, ‘It appears that Onuora’s creative attitude and studio experiments further fired my imagination to explore carved lines and glaze colors in my ceramic vessels.’3 To a considerable degree, this informed his early carved ceramic wares: altered and distorted carved wheel-thrown tea sets, cups, and pitchers with inspiring appendages. This creative spirit and style became a launching pad, a point of departure for the current Onuzulike dotted lines.

Styles

Evidently, Onuzulike’s free nonadherence to orthodox ceramics evolved over the years, creating conventional shapes and forms. Eva Obodo, a sculptor and a professor of art history, observed that, starting from distorted wheel-thrown pieces, his thrown pieces ‘are reshaped by pressing or beating strategic parts inwards or outwards; to make them appear dynamic and elegant, legs of clay stumps are fixed to some of the pots particularly teapots and even cups, akin to the traditional aluminum tripod pots.’4 Hence, he progressed to lumpy, pinched human forms such as free-standing forms (politicians) in a combination of pliable and nonpliable materials, as some of these humanoids were hung from tree branches and traditional colanders in his suicide series; then pinched clay slabs strung with metal spokes in semblance of the traditional Nigerian suya (kebab) installed on logs of wood and in barbecue settings in the Suyascape series. Also, Onuzulike explored yam tubers in a body of work where yam seedlings were cast with plaster of paris and silicon. Thereafter, the clay yam tubers were pressed out of the molds in their realistic forms. Concurrently, he ventured into coins, making hollowed and solid coins and palm kernel shell beads. In like manner, bee hives are another body of work Onuzulike is exploring.

In the amassed body of artworks, Onuzulike is addressing issues surrounding politics, colonialism, globalization, global warming, and climate change.

Dotted Lines

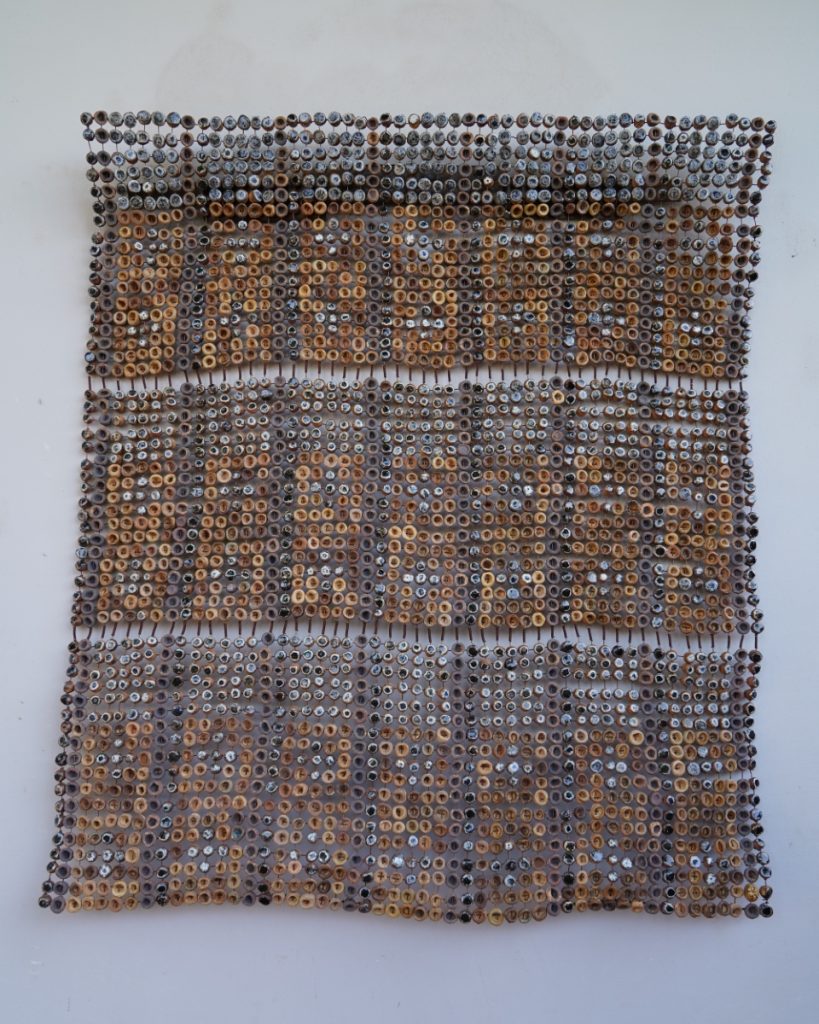

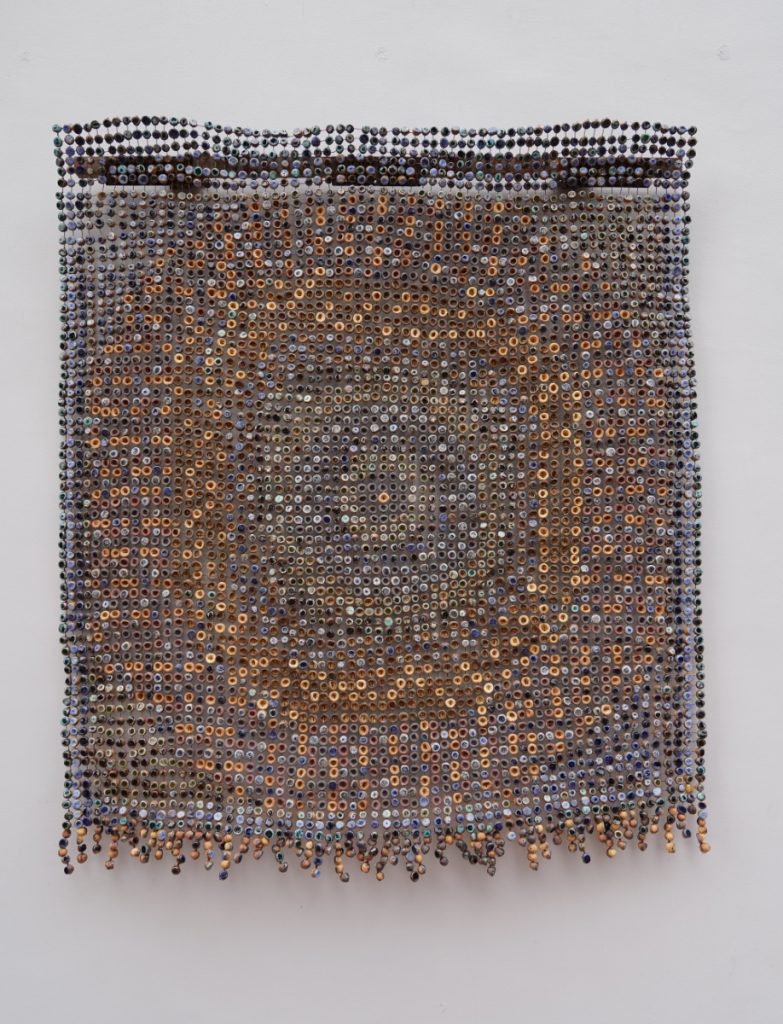

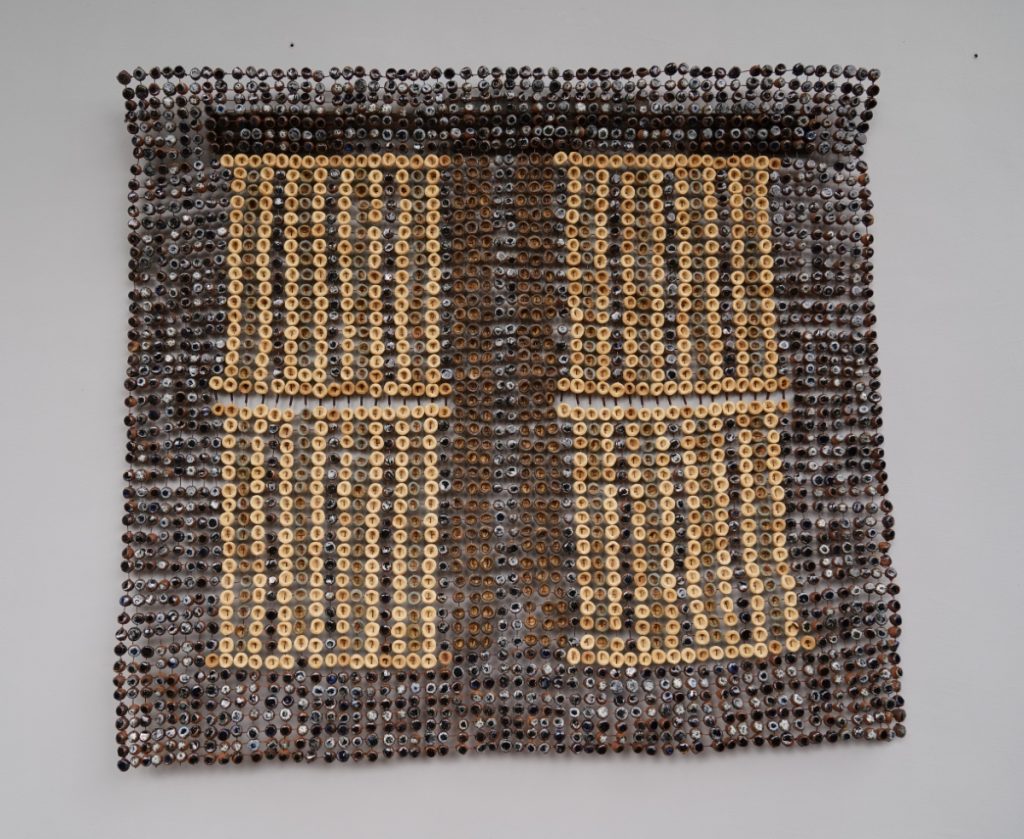

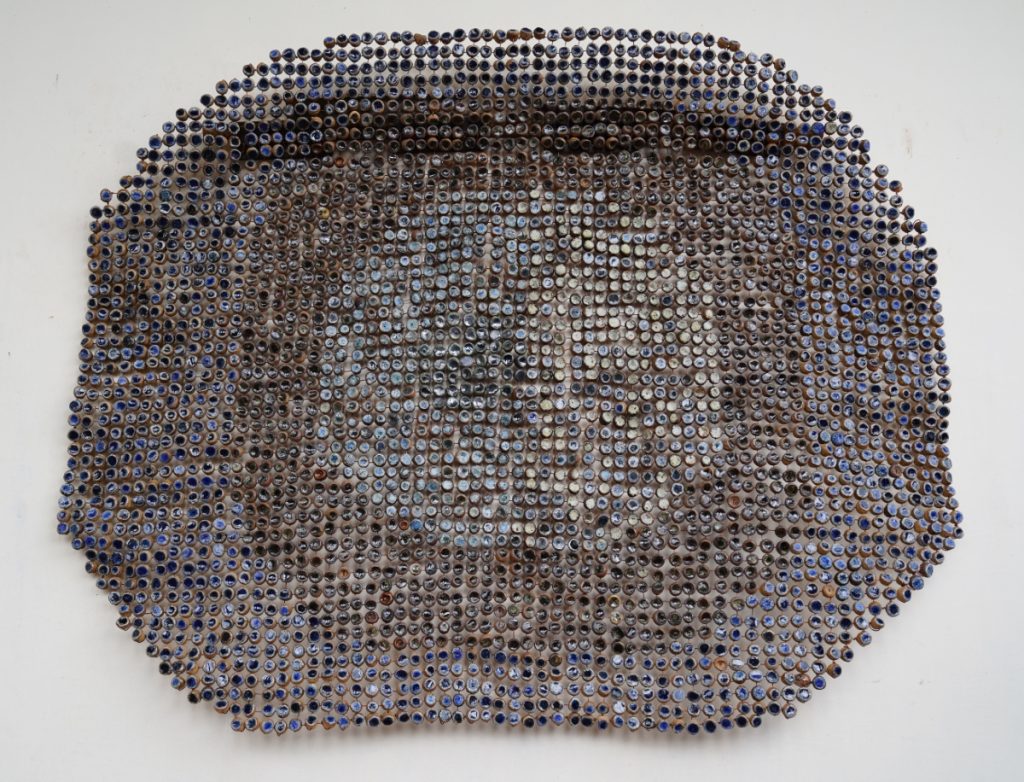

In the course of his explorations—pinching, punching, pressing, hammering, hanging, slabbing, slapping, tying, and warping the clay medium—Onuzulike has revolved back to the lyrical lines he started with in the gouged tea sets and other wheel-thrown pieces. A survey of his new directions and the body of artworks in his ongoing exhibitions confirm this observation. Obviously, these dotted lines might not be an intentional or direct representation of uli lyrical designs. However, a detailed study of the structures of the woven artworks does not deny the resemblance to kpom kpom (dots), another uli symbol. Inherently, each artwork appears as a cluster of thousands of kpom kpom converging in vertical, horizontal, squared, and curvilinear arrangements.

Production Processes

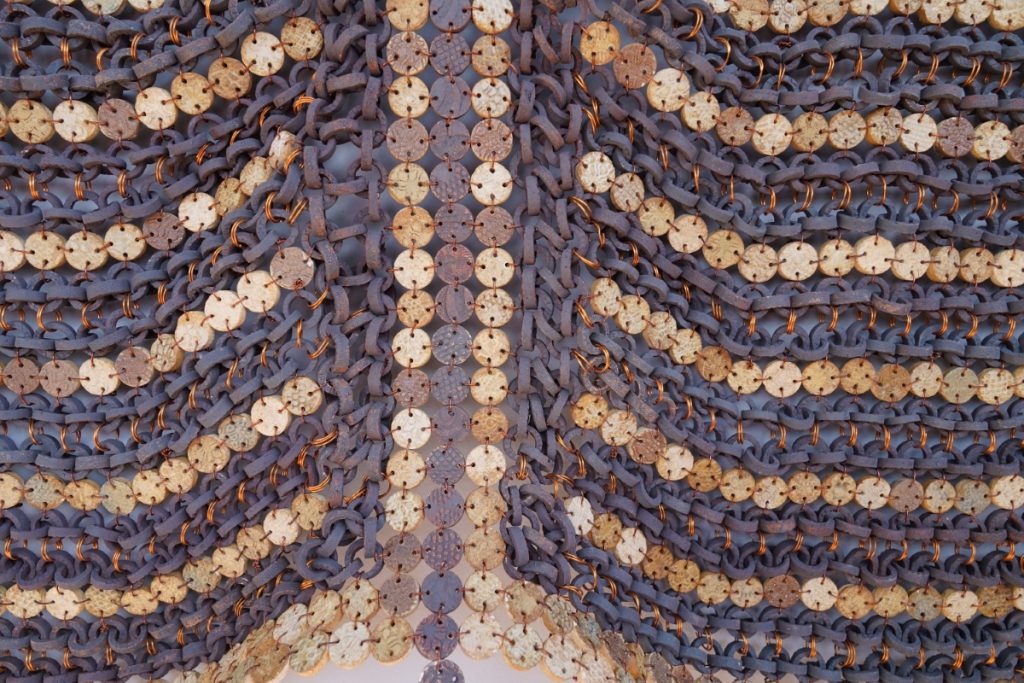

To create his art, Onuzulike relies on locally sourced ceramic materials—fire clay, stoneware clay, ash glaze, and recycled glass. Utilizing these clay bodies for different hues and shades as well as green strength, ceramic palm kernels of various sizes are individually pressed out of the plaster of paris mould in large numbers. The palm kernels are perforated at the right stage of hardness to become bead-like. Afterward, they are bisque-fired to nine hundred degrees centigrade. Ash glaze and recycled glass are inlayed in the depths of the clay kernels, invariably filling the space that the nuts would have occupied. Then, they are gloss-fired up to twelve hundred degrees centigrade in a gas or electric kiln. Utilizing copper wire, the ceramic palm kernels are woven together to create different clothing forms, though not wearable because of their nature and heaviness.

Marc Straus, in a press release during Onuzulike’s exhibition in New York in September 2023, expressed his opinion that Onuzulike ‘uses these new beads to weave textile structures that remind one, not of the slave trade era (of which Onuzulike addresses in some of the artworks), but instead of Africa’s prestigious cloths like the Akwaete of the Igbo of Southeastern Nigeria, the Kente of Ghana, and even the Aso-oke of the Yoruba people of Southwestern Nigeria.’5

When Hearts Beat with Lofty Dreams, an exhibition of Onuzulike’s ongoing solo show of ceramic installations in Afikaris Gallery, Paris, France, consists of ceramic palm kernels and ceramic yam tubers. The focus of this major presentation is on the two outstanding series in his current body of works, namely the palm kernel shell beads and seed yams of our land projects.

A ceramist, poet, and professor of African art history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Onuzulike uses these artworks in this first solo show in France to explore the notion of social elevation and weave the hope of equality. Strategically curated, the artworks were hung on the walls and installed from the ceiling to the floor. Having the form of regalia, the palm kernel beads are woven together as symbolic relics of the upper class of Nigerian settings. Afikaris Gallery described it this way: ‘Onuzulike’s imperial blouses, babariga, and royal shirts, sometimes in lace and alligator skin patterns, carry with them both conceptual and ornamental functions. The weight and size of these items make them unwearable adornments. Any utilitarian notions disappear, elevating them to the status of objects of power. Like precious relics preserved in a museum, protected from time, use, and damage, they become the privileged witnesses of an era in the throes of mutation.’6

The seed yam of our land is displayed in the inner gallery room. In this section, arrays of assorted ceramic yam tubers are tied together in mimic reflection of a traditional Igbo man’s yam barn. In traditional African societies, where yam is considered a precious commodity, particularly in Igbo communities, the size and quality of the yam seedlings is a yardstick to measure one’s economic status. Thus, Onuzulike uses this precious crop to interrogate exploitation, devaluation, and the ongoing brain drain in some African countries, particularly Nigeria.

Ozioma Onuzulike joins the growing numbers of African artists who use traditional materials and motifs to express political and socio-economic circumstances on their continent.

Ngozi-Omeje Ezema is an artist born 1979 in Nsukka, Nigeria. She graduated from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 2005, Department of Fine Applied Arts, and obtained her Masters of Fine Arts in the same Department and Institution. After completing her MFA, she was retained as a lecturer in her Alma Mata to teach Ceramics since May 2009. Ngozi-Omeje has participated in several national and international events such as the Abu Dhabi Art Fair, United Arab Emirates, the Korea International Ceramics Biennial and the Cheongju International Craft Biennale, South Korea, and the 60th Faenza Prize, Italy.

Captions

- Royal Mask for the Jagaban IV, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (3,813 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 175x143x10 cm

- Royal Jumper with Embroidered Shine-Shine, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (5,695 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 198x160x13cm

- Beaded Regalia for Sanusi II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (4,914 ceramic and natural palm kernel shell beads), 163x133x10cm

- New Lace Material for the First Lady, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (2,420 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 132x116x10 cm

- Thick-Madam Blouse with Kente Weave, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (2,828 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 143x134x10 cm

- Ada’s Three Piece Lace II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (2,754 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 135x120x10 cm

- Thick-Madam Blouse with Earth Colours, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (4,881 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 178x163x14cm

- Patterned Lace for Wike, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (6,537 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 225x188x12cm

- Extra Large Babariga for Akpabio, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (27,090 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 338x280x15cm

- Peacock Weave II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (4,685 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 180x160x10cm

- Akwaete Woman’s Weave II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wires (2,800 ceramic palm kernel shell beads), 121x134x9cm

- Zipped Armour for Obi II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, iron oxide engobes and copper wires, 130x113x10cm

- Royal Mat III, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, ash glazes, recycled glasses and copper wire, 120x160x8cm (35kg)

- Yam Barn: Of Harvest and Mixed Feelings, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, iron oxide engobe, recycled glasses, burnt wood and copper wire, 131x221x11cm

- Ageing Beehives, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, iron oxide, ash glazes, recycled glasses and burnt wood, 130x194x4cm

- Yam Barn: Of Harvest and Scorched Earth, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, iron oxide engobe, burnt wood and copper wire, 122x219x13cm

- Honeycombs II, 2023, earthenware and stoneware clays, iron oxide, ash glazes, recycled glasses and burnt wood, 141x189x4cm

Footnotes

- H. C. Ngumah, ‘The Influence of Linear Style on Nsukka Ceramic Art Forms,’ CPAN Journal of Ceramics, Nos. 2&3, 2000

- Don Akatakpg, The Zaria Art Society: A New Consciousness, (link)

- Eva Obodo, ‘Ceramics Sculpture: Ozioma Onuzulike’s Exploratory Tendencies,’ CPAN Journal of Ceramics, Nos. 2&3, 2000

- Ozioma Onuzulike, ‘Towards the Unique and the Light-Weight: Carving the Ceramic Vessel,’ CPAN Journal of Ceramics, Nos. 2&3, 2000

- Marc Straus, ‘Ozioma Onuzulike’, Sept. 2023, (link)

- Afikaris Gallery, Ozioma Onuzulike, Nov. 2023 (link)