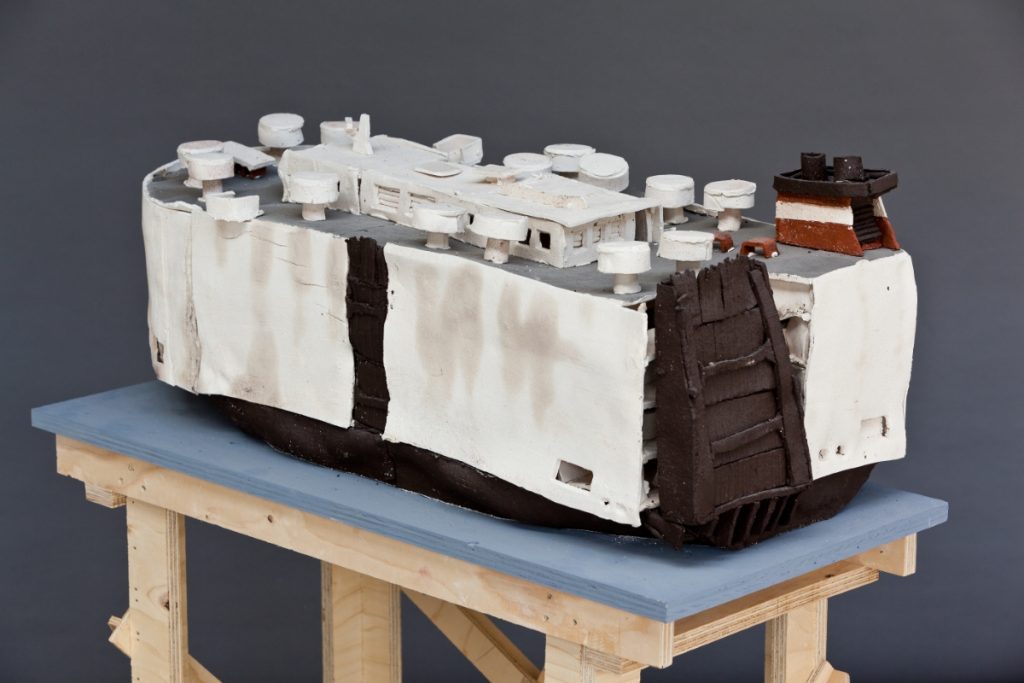

Supertanker, 2016, 189 x 51 x 36 cm (Photo Ad van Lieshout)

Supertanker, detail view (Photo Mark Weemen)

Containerriese, 2016, 228 x 59 x 50 cm

Carcarrier, 2016, 79 x 34 x 31 cm

Feeder, 2016, 104 x 31 x 31 cm (Photo Mark Weemen)

Fishtrawler, 2016, 65 x 22 x 28 cm (Photo Mark Weemen)

Bananedampfer, 2016, 104 x 31 31 cm

Tilmann Meyer-Faje: Full Speed Ahead, 2016

How many ships does it take to rightfully talk of a fleet? Tilmann Meyer-Faje built seven of them during a work period at sundaymorning@ekwc. His studio, which was open to the public, had been transformed into a yard where productivity and diligence are as tangible as the clay he is working with. At each new visit, yet another part of the 1.93-meter-tall Supertanker has been finished and Meyer-Faje has already started construction of the next ship. Bottom, ribs, hull, deck, pilothouse, railing: a life-long fascination is being translated into highly individual sculptures with industrial efficaciousness. A feeder, a banana boat, a car carrier, a trawler… Once they have been fired and installed, the ceramic ships look rusty, imperfect, ready for the scrap heap – and at the same time they are bursting with expansive energy: you can easily imagine the fleet grow into hundreds of vessels, you can see the terminals, the yards, the cranes, the trucks that carry the containers into the hinterland.

With its ever expanding cargo, the 2.28-meter-tall containership Containerriese represents one of the driving forces of globalisation. Shipping has become so cheap that the distance between production sites and the markets have become all but irrelevant. Take that cute blouse for the upcoming summer season: the cotton comes from the United States, the fabric has been woven and dyed in India, the buttons come from Vietnam, the label says ‘made in Bangladesh’ and you can still buy it off the rack for a few tenners. That is container transport – that and low wages, depressing working conditions on board, tax evasion, pollution, ship graveyards on the beaches of India and Bangladesh – stop! Enough. That’s not what the work is about. Or it is, but only in hindsight.

To Meyer-Faje, making is all that matters. During the production process, he feels liberated; any thoughts about the dominant influence of worldwide trade on our daily lives are being replaced by practical questions. How to prevent the hull from cracking in the kiln? How to make the construction both lighter and more stable? Gradually, building the ships becomes an almost meditative process; the designer has become the executor. He watches while the sculptures come into being under his hands and the underlying principles become apparent. This contemplation clings to the ships: despite their destituteness they seem to be made to withstand the issues of the day. Not a bad quality in these turbulent times.

Text by Nanne op ‘t Ende