Claire Partington: When the rocks were soft is on view at Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh

September 28 – October 29, 2023

Scottish folklore is full of fairy changelings – unearthly beings who take the place of human children lost to, or stolen by, the fairies. Nan MacKinnon, a tradition-bearer from the outer Hebridean island of Vatersay, tells of a woman whose suspicions are aroused by her baby’s sudden insatiable and uncanny appetite for porridge. A village elder instructs her to leave the child on a rock surrounded by the rapidly incoming tide; sure enough, for fairies cannot cross salt water, the infant shape-shifts into ‘an old fairy bodach’, who threatens and curses her. The mother stands strong, demanding the return of her stolen child; the faes comply and, at least briefly, equilibrium between human and otherworlds re-aligns.

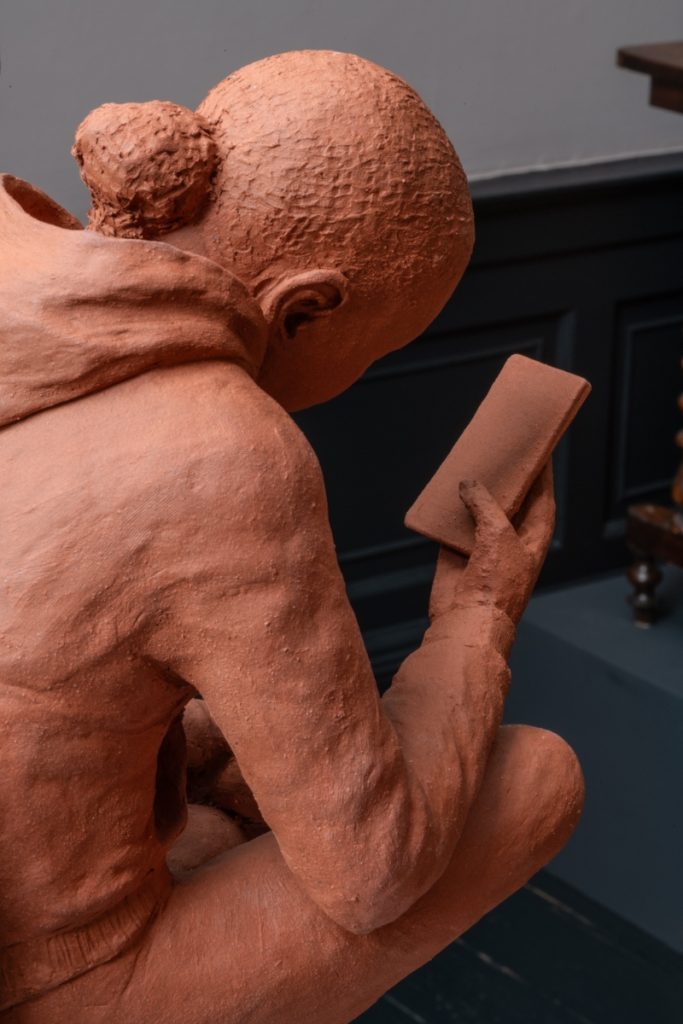

MacKinnon’s telling of the changeling narrative which permeates Celtic folk traditions captures the rapid, unpredictable, shape-shifting turns of uncanny spirit worlds, and their emotional powers, a theme which runs through all of Claire Partington’s pieces for this new exhibition. The ghost of Mackinnon’s uncanny child might be seen in Partington’s ‘Changeling’, whom we see crawling, as if towards, or away, from something; embarking on a journey, or perhaps waiting for, like all of Partington’s sculptures, they possess a stillness which is full of immanent movement. New-born and vulnerable yet solid and embodied, their tiny gold crown summoning the image of the ‘royal child’ of fairytale, they are literally etched with words. Their body, young and old and timeless all at once, bears the imprint of every ambivalent changeling, on the cusp of change, as if caught between stories.

There are echoes and hallmarks of some of Partington’s earlier work in this exhibition’s use of the symbolic and visual languages of folklore, fairytale, myth, and magic. This is entwined with elements of the sacred and mystical, as in ‘Simultana’, an elemental goddess-being of physical and cultural hybridity; evocations of medieval Madonnas, and the miraculous, magical bodies of female saints; or the spiritual and folk iconographies of ‘Unicorn’ which, so characteristically of Partington’s craft, meld together the powers of the feminine and the creaturely. There are multiple criss-crossings of culture and temporality in these pieces; but the distinctive, uncanny textures of Scottish folk and fairy traditions are persistently manifest, incarnating stories of selkies, mermaids, and kelpies gathered from the shorelines of Scotland’s archipelagic islands and coasts.

Such stories live on the edge between oral and literary cultures, and in the liminal spaces of Scottish folk tradition; here, fairies are far removed from the winged ethereal sprites of 19th century representation and embody the capricious, carnivalesque energies of the medieval folk imaginary where fairies and witches are in alliance. From the early medieval period onwards, poetry, tales, chants, riddles, prayers, and the like, composed in the historical and geographical range of Scotland’s different languages – Gaelic, Scots, English – speak of the emotionally

charged connections between spirit and human worlds. The faes, or the sìthchean, whom the great Gaelic folklorist and collector, J.G. Campbell, called in English ‘the still folk, the noiseless people’, could take away and destroy as much as they blessed and saved – livestock, a child, a dwelling, a lover. Traditional ballads, tales, and stories pay homage to these fragile and intense relational bonds; when it comes to the rituals of human love and life, birth and death, the folk spirit world is always close by.

A late 17th century treatise written by Robert Kirk, minister of the parish of Aberfoyle in the Trossachs, entitled The secret commonwealth, or, An essay on the nature and actions of the subterranean (and for the most part) invisible people heretofore going under name of elves, faunes and fairies, bears witness to this arresting universe in a striking fusion of magical and scientific thought. Its busily occupied, diverse, and viscerally corporeal ‘ministry of spirits’ are located between the realms of spirit, earth, and air, co-existing alongside a more orthodox world of supernatural divinity. Like many spirit worlds, Kirk’s is also fragile, on the point of extinction, its beings infused with a kind of resistant yet melancholic energy.

Something of this fragile yet powerful embodied energy echoes through these sculptures. Like Kirk’s sprit beings, these faes seem ‘earthed’ to their world through soft yarns of wool; the luminescence and texture of skin, its sheen and warmth; the ripples of hair; the gold of jewellery. These evoke the materialities of traditional ballad language – the shining rings, bells, mantles, cups, and jewels exchanged between fairy lovers, sisters, daughters, mothers. These beings are caught, too, in moments of quotidian embodiedness; beach shoes and sun lotion gather up the talismanic powers of more transparently magical objects, such as the horseshoe. They are anchored in layers of landscape, waves of marbled colour resembling geological layers, as if sand, rock, stone, water had become one. Everything, and everyone, is ‘on the cusp’: the selkie seems half-way between shore and sea; the kelpies appear to be making their way, gently, playfully, towards the water’s edge; the mermaid looks poised, entwined in herself and waiting, on the rock. They seem like embodied echoes of the fairy beings of traditional Scottish lore and literature who belong in, and of, the hollows of the earth; the greenness of fairy mounds; between woods and water; the depths of river, pool, and sea. Glimpsed only at special liminal times of year – Midsummer Eve or Halloween when the membrane between worlds is thinnest – or by the gifted, blessed, or unwary, they live at the edges of our vision, the spaces-in-between. So too do these sculptures, seeming to harbour a choreography of immanent motion which we happen to come upon.

We interrupt some of the protagonists in moments of encounter. In ‘Wurm’, maiden and serpent are locked in a stilled moment of immense physical energy. Like a virgin-maiden from mediaeval romance, her spear is drawn with sharp certitude against a creature, freighted with resonance from biblical myth and vernacular legend (the ‘Stoor-Wurm’ of Orcadian tradition springs to mind). Coiled in conflict, she bears an echo of Mélusine, from medieval French legend, cursed by a fairy mother to transform into a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. Within each sculpture, then, lie inner strata of stories, like the rippled layers of geological colour on which the water-figures sit.

Elsewhere, as in ‘Card Game’, the protagonists seem like conspirators, rather than adversaries – their exchange of gazes, and the placement of cards, suggesting unfathomable processes of withholding, knowing, (mis)trusting. In each sculpture, the gaze – its focus, ‘holding’, and depth – becomes the locus of emotional experience which we, in looking back, imagine. The Faeries seem to watch with a hard purity of line and vision, though Faerie 3’s gaze seems to catch a flicker of anxiety, as if encountering something beyond. ‘Kelpie’ presents a tender family moment where bodies – parental and child – seem caught up in gentle spaces of light, joy, and play. This is an unexpected and beautiful embodiment of the kelpie, more familiarly known in Scottish lore as a masculinised, shape-shifting water spirit, incarnate on land as a horse, who practices tricksy malevolence. Instead, Partington’s ‘Kelpie’ weaves images of the creaturely, the feminine, and the intimate into gentle life.

Sculptural form, then, crafts a new and distinctive imaginative language for these enduring layers of myth and belief. ‘Selkie’ gives powerful expressive weight to the affective power of the seal-maiden story which runs deep in Scottish and Irish lore. Half-human, half-seal, they are ‘in between’ beings whose erotic encounters with mortals – sometimes ending in marriage and the bearing of children – can spell eternal, land-locked separation from their own kind, ‘the people of the sea’. Only re-possession of the sealskin that was shed (or stolen from them) to enter mortal life ensures free return and loving re-integration with their creaturely selves and kin – even when that means the loss of their human family. The bend, curve, and weight of Partington’s selkie – the heaviness of their gaze, deflected from us – speaks of the emotional depths of selkie legend, with its tracery of grief, memory, and unbelonging. Always on the cusp, at the edge of vision, the shoreline of imagination – these sculptures spell a new becoming for these stories.

Essay by Sarah Dunnigan, 2023

Sarah Dunnigan teaches at Edinburgh University, and has published on diverse aspects of Scottish literary history, including women’s writing, medieval, traditional, and children’s literature. She is currently writing a book about fairies in Scottish literature.

Contact

info@arushagallery.com

Arusha Gallery

13A Dundas St

Edinburgh, EH3 6QG

United Kingdom

Photos courtesy of Arusha Gallery, © ZAC and ZAC Photography