Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren present Revealing the Earth. Histoires de céramique at Musée du Vieil-Aix, Aix-en-Provence and Tuilerie Bossy, Gardanne, France

June 16 – November 5, 2023

The exhibition at Tuilerie Bossy will close on September 16, 2023

Nourishing a unique history with provencal ceramics, the Museum du Vieil-Aix and La Tuilerie Bossy (Gardanne) wished to associate to honor contemporary creations.

Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren, world-renowned artists, are the leaders of this project. Their extensive career spanning forty years will be the subject of a retrospective, giving the museum free rein to showcase their works. At the same time, their legacy will be examined at La Tuilerie through a dialogue with the works of young ceramists in training at the National Art and Design School of Limoges, as well as with the ceramists of La Tuilerie who are paying tribute to them.

As a land of ceramic creation, Provence has been home to numerous artists and artisans who have excelled in this art during the 20th century. Several exhibitions have shed light on this flourishing of artistic productions, whether it’s “10 Aixois Ceramists” (Musée Granet, 1994) or, more recently, “The Buffile Workshop: 70 Years of Ceramics in Aix” (Musée du Vieil Aix and Pavillon de Vendôme, 2017). A sign of renewed interest in ceramics and a testament to its prosperity, the School of Art in Aix recently reopened a ceramic course for students. In this context, the ceramist couple Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren were trained, particularly under the tutelage of Jean Biagini in the 1970s.

At Tuilerie Bossy, the following students from the National School of Art and Design of Limoges specializing in ceramics will accompany Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren: Lou-Lolita Arnon, Choi Hyein, Leticia De Souza, Till-Nathanael, Victore Chiens, Jade Tailhander, Karina Ticona-Nava, Yang Yiyang. Local ceramists from Tuilerie Bossy: Doris Happel, Anne Larouze, Aurélia Rocher.

Underground links

Essay by Jean-Charles Hameau, Heritage Curator at Musée national Adrien Dubouché, Limoges

The exhibition Revealing the Earth. Histoires de céramique showcases the work of Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren, two ceramists who, thanks to the consistency of their work and the originality of their respective approaches, now occupy a special place in the French and international ceramics landscape. While it is impossible to provide an exhaustive account of their careers, their inspirations, their travels and their creations over more than forty years, this exhibition would seem to be the ideal opportunity to highlight the topicality of their work and how their work echoes the issues that are shaking up the art world in general and contemporary ceramics in particular. This topicality invites us to reflect on what characterizes their work and the forms and ideas that resonate with the present in each of them. It also invites us to underline the lines of force, visible or invisible, woven throughout a shared life and within a shared studio.

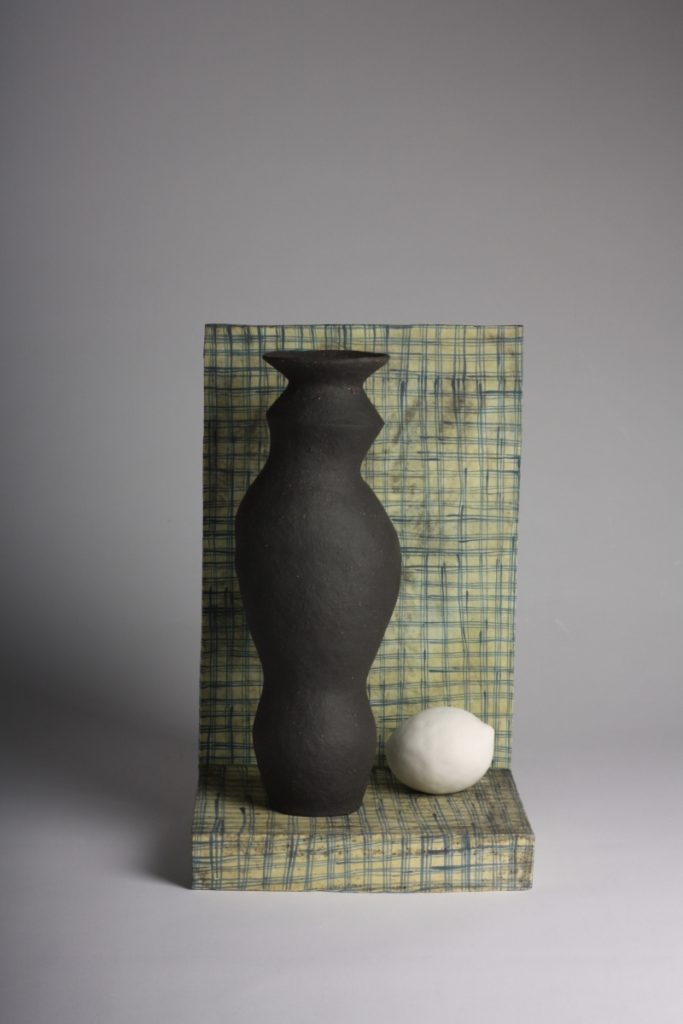

Daphne Corregan

Like the chairs, vases, pots and jugs that dot her work, the role of objects is central to Daphne Corregan’s work. This might seem obvious, given that the history of ceramics is inextricably linked with the pot, the utilitarian piece and its infinite formal variations. Yet Daphne’s relationship with her objects is not based on a logic of manufacture in the classical sense of the term, based on a fixed repertoire of forms inherited from a potter’s tradition, nor on a representation foreign to materiality. In working with clay, Daphne Corregan engages in a dialogue with the vessel on the one hand and its image on the other. The shadows cast by these objects permeate universal visual culture far beyond the medium of ceramics. Indeed, the artist herself sees her works less as pots or jugs and more as “images of pots, or images of jugs” [1]. Her regard for cubist painters such as Picasso or Braque, or ceramicists such as Betty Woodman, whose ambition she shares to reveal the object from every angle, is logically perceptible. But beyond the optical challenge, it’s about underlining the life of the objects we create or inherit, paying homage to their capacity to shape humans in return, transforming their gestures and imaginations, their mental landscape as much as their everyday environment. Daphne Corregan’s recent works feature objects that become contaminated, that escape their form and condition, moving freely from table to wall, from vase to flower [2]. They echo the work of artists and researchers who emphasize the “agentivity of objects” and describe “things” that escape the passivity with which they are traditionally associated. This relationship with objects logically leads Daphne Corregan to represent them as embodied beings and to consider them plastically as living bodies. Some of the works inspired by masks and dresses she created in the 2000s feature objects destined to be in contact with the human body, and capable of translating what drives it, what questions it or what troubles it. Treated in smoked black clay and pierced by claustras that evoke the burka, the dress becomes the medium for a political view of the female body, and of the disproportionate gap between its enhancement and its concealment, depending on the region of the world [3]. In Daphne Corregan’s work, the body is generally fragmented, seen as a vessel, not to reduce it to the status of an object, but to show its interior, which is often decorated, to signify the collection of memories, emotions and scars left by History, war and exile, or the more personal scars of individual histories. This focus on a part of the body (feet, heads, hands, bellies) and the play of combinations with vase forms enable her to sidestep strict figuration and draw attention to the interactions that are constantly taking place between the human and material things, as in her “column” sculptures charged with the memory of African women who carry pots on their heads [4]. For Daphne Corregan, the body is also the medium for her work on ornamentation, sometimes in the form of a motif that covers the body like a textile, sometimes like a tattoo engraved on the skin of the work using the sgraffito technique. Here again, the travels that have nurtured her visual culture come to the fore, from the ritual scarification so prevalent in African cultures to the henna-decorated hands of Indian women [5]. Her interest in folk art and non-Western cultures, where the hierarchical distinction between fine and decorative arts is non-existent, is no stranger to the freedom with which she represents or even presents flowers on or in her works. Instead of the great tradition of glazing and the technical virtuosity that often characterizes it, Daphne Corregan prefers textural effects: traces of smoke, whites dirtied by the sought-after resurgence of a black undercoat, rubbed, oxidized aspects [6]. Her palette gives her works the patina of objects that deteriorate, bearing the marks of time and use. This reflects her interest in the material fragility of things, as much as in human beings and their physical and psychological vulnerability. In addition to surface treatment, the diversity of the materials she works with (stoneware, porcelain, terracotta) and the techniques she uses to shape her pieces (throwing, coiling, slabs) is a form of tribute to the art of ceramics, its specificities and its own qualities. Her participation in the “Projet Afrique”, launched by ceramist Camille Virot in the early 1990s to learn more about African pottery techniques, bears witness to the importance of practice in her work. Daphne Corregan has thus played, and continues to play, an important role in a generation of artists who are asserting, in contemporary art, the permanence of decorative art in general and ceramics in particular, and their capacity to be aesthetic and political tools of vitality, freedom and emancipation.

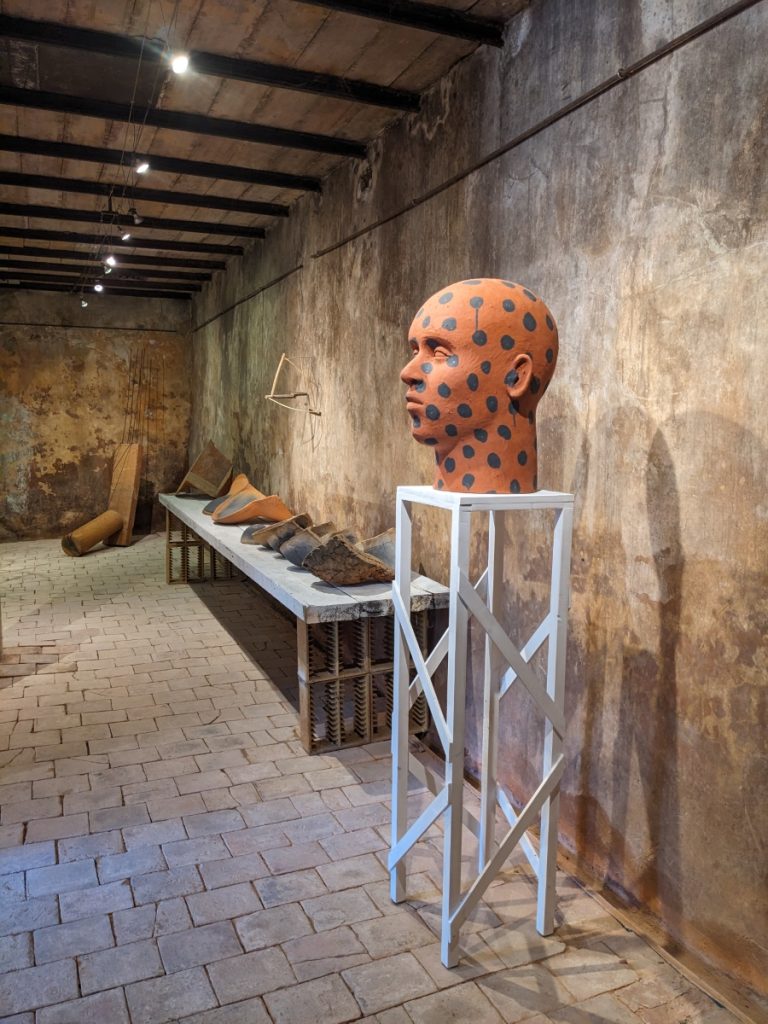

Gilles Suffren

Alongside artists such as Daniel Pontoreau, Jacques Kaufmann and Claudi Casanovas, Gilles Suffren belongs to a generation that has exploited the sculptural potential of ceramics in large-scale installations. If clay is important in his approach, it’s less for its link with the vessel than for the material’s ability to form rigid masses, counterweights that are both aerial and anchored to the ground [7]. His work is based on a search for balance between volumes, often made of terracotta and linked together by wire. Extruded, coiled or, more frequently, molded or rammed like cement or concrete, the ceramic parts form the ends of large pendulums, pieces of clay raised by the artist to make them move « standing on pointe, like dancers “. From a simple question, “How does it stand up?”, Gilles Suffren, an architect by training, builds unstable structures. His abstract sculptures are akin to “machines à rien”, mechanisms for testing gravity and defying gravitation [8]. He readily admits to having been impressed by the blockhouses on the Normandy coast, by these colossal abandoned and sometimes ruined edifices on which we can see fragments of concrete held in balance by a few remnants of the metal reinforcement that strengthens them. This fascination, perhaps tinged with a form of unease or concern in the face of the fragility of human constructions, is perceptible in his large-scale pieces, which engage in a dialogue with the space and techniques of the construction: they replay the tensions at work in a suspended bridge, a vault or an overhanging roof [9].

However, his interest in construction is not confined to the architectural scale: it is also expressed in works of a more modest format, in assemblages of solid, dense parts in clay, metal or plaster, and voids revealed by a wooden rod or a wire that seems to draw a line in space [10]. Through his research and the innumerable models scattered around his studio, Gilles Suffren has developed a truly three-dimensional language that is both personal and echoes the history of modern sculpture, from EL Lissitzky’s PROUN spaces to Anthony Caro’s metallic compositions. As a child, Gilles Suffren played with superimposing his cutlery to create small, precariously balanced sculptures. From this playful relationship with assembling, he has retained a taste for a spontaneous practice marked by an economy of means that affects not only the technique and materials employed (those at hand), but also becomes an aesthetic bias: if some works are pared down or even stripped bare, it’s less for stylistic effect than to avoid distracting the eye from the tensions and movements he creates [11]. He sometimes abandons ceramics in favor of recycled materials (branches, crates, pieces of cardboard), which he likes both for their shape and for the lack of ecological impact their use implies [12]. For him, ceramics is not a sacred artistic discipline laden with rules and constraints; it is, above all, a sculptural material, as much available for bricolage as for building a house. In fact, he practices both activities, switching from one to the other with ease, without seeing any contradiction or submitting to the social imperative of regularity or exclusivity in professional activity.

His practice of ceramics thus reveals a vision of creation that frees itself from the hierarchies separating technique from artistic gesture. His eyes light up when he recalls the astonishment and emotion provoked in children by the use of a simple crowbar, capable of levering a rock weighing several hundred kilos. He is sensitive to the beauty of tools: his taste for mechanisms is illustrated by the objects he and Daphne Corregan collect, such as a Chinese anti-theft device or a Dogon padlock brought back from a trip. By focusing as much on finished form as on tools and their physical and relational capacities, Gilles Suffren makes tangible a relationship to materials and technical devices well described by Bruno Latour and to which many ceramists are currently receptive.

Lines of force

Despite the specificities of their respective aesthetic language, the two artists share much in common. Gilles Suffren’s streamlined constructions [13] are matched by Daphne Corregan’s small-scale architectures, which capture the poetics of space and the luminosity of colored plaster [14]. In both, we find a desire to make space visible, a desire for architecture expressed in ceramics as an alternative to the built environment. Faced with Gilles Suffren’s shelves full of models, or Daphne Corregan’s work such as Shades of Brown [15], a veritable “skyline of pots”, sometimes glazed, sometimes smoked, we find the same ability to transform everyday, domestic things into a constructed landscape, a microcosm of the city in which their visual memories and imaginations crystallize. Their works transpose into ceramics, which fascinated the painter Giorgio Morandi and the architect Aldo Rossi.

Their shared taste for systems of connection between two volumes, for compositions linked by a wiring or an excrescence, is another line of force that unites their approaches and their works. Daphne Corregan’s Two Bellies [16] presents two spherical wombs linked together by a shape and a decoration to create an organic solidarity between the offspring. The energy symbolically transmitted by the umbilical cords visible in his work expresses, in other ways, the physical strength of the cables that, in Gilles Suffren’s work, enable his constructions to stand upright[17].

The idea of a passageway between two spaces is also reflected in the porosity of their pieces (open forms, openings, pipes, chimneys, funnels), which allow air to pass through and enable a sculpture to breathe or communicate with the outside world [18, 19, 20]. More than a formal principle, these links reflect the generosity of two artists sincerely committed to transmission in all its forms. The exchange functions first and foremost on the scale of the duo they form, both in the city and in the studio, when, for example, one collects the other’s pieces and vice versa or when they create joint pieces, one form being complemented by the other’s work. It’s a sign of freedom and a clear bond of trust to entrust the other with the task of modifying a work, altering it, and allowing oneself to be surprised. Of course, the transmission of knowledge also takes place through contact with other artists, through curatorial work for the former, and teaching for the latter. Over the course of its millennia of history, ceramics has long been an anonymous and collective art form, linked as it is to the need to gather forces to extract the raw material, ensure a firing, and to the specific skills required to perfect a clay body, shape it or decorate it. In the face of social and environmental crises that indict Western deafness and individualism, Daphne Corregan and Gilles Suffren update and make visible a material and cultural link that can be taken care of by ceramics.

Contact information

Musée du Vieil-Aix: Christiane Aublet, 04 88 71 84 45, aubletc@mairie-aixenprovence.fr

Tuilerie Bossy: Daniel Bossy, 06 16 17 78 52, expo@tuileriebossy.com

Musée du Vieil-Aix

17, rue Gaston Saporta

13100 Aix en Provence

France

Tuilerie Bossy

1285 chemin du moulin fort

13120 Gardanne

France

Citations

[1] The recent exhibition Les choses (Musée du Louvre, October 12, 2022-January 23, 2023) curated by Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and her essay on the subject, Pour en finir avec la nature morte, Gallimard, Paris, 2020, spring to mind.

[2] See her description of this series of works in a lecture given at ENSAD Limoges on November 8, 2022, online video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBKekHJrx8I&list=PLZZ7jpgQvfsTr52HQRqxapEuW5QRyvhmP&index=5, accessed 05/05/2023.

[3] “During an exhibition at Galerie Sarver, Daniel Sarver told me: ʺthis is art, you can’t put flowers in it!”ʺ I had to fight to show my piece with flowers in it, and I’m proud of it.”, lecture at ENSAD Limoges, Op. cit. 4 See Camille Virot, La poterie africaine, éditions Argile, La Rochegiron, 2005.

[5] On the subject of ceramics, see Anne Dressen, “La révolution permanente de la céramique” in Les flammes, exhibition catalog, Paris-Musées, 2021. See also for the question of ornament the work of Thomas Golsenne and in particular “L’ornement aujourd’hui”, Images Re-vues [En ligne], 10 | 2012, put online on , accessed 02 May 2023. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/2416 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/imagesrevues.2416

[6] “It’s a relief for me to make pieces in wood, without clay, there’s no firing, no Co2 that goes into the atmosphere, it’s not bad.” conference at ENSAD Limoges, November 8, 2022, Op. cit.

[7] See Bruno Latour, Petites leçons de sociologie des sciences, la Découverte, Paris, 2007.

[8] We’re thinking here of Aldo Rossi’s drawings, in which he shows his work table, the objects on it and the way they inspire him to create architectural forms and solutions. See Carter Ratcliff, Aldo Rossi drawings and paintings, Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

[9] On this subject, see Alain Macaire, “Figures du doute”, in Dialogues céramiques, Gilles Suffren, Exhibition catalog, Musée d’art contemporain, Dunkerque, 1994.

Photo Captions

- Daphne Corregan, Still life with cake, 32 cm h, terracotta, 2022 © Gilles Suffren

- Daphne Corregan, Black vase and white lemon, 40 cm h, stoneware, porcelain, 2023 © Gilles Suffren

- Daphne Corregan, Breathing, 67 cm h, terracotta, 2022 © Philippe Biolato

- Daphne Corregan, Still life with Black Flowers, 56 cm h, 2023, stoneware © Gilles Suffren

- Gilles Suffren, Agrégat, 97 h cm, terracotta, iron, 1996 ©Philippe Biolato

- Gilles Suffren, sans titre, 40 cm h, terracotta, wood 2023 © Gilles Suffren

- Gilles Suffren, sans titre, 41 cm h, smoked clay, wood, 2023 © Gilles Suffren

- Gilles Suffren, sans titre, 42 cm h, terracotta, iron, 2023 © Philippe Biolato

- Gilles Suffren, sans titre, 43 cm h, terracotta, iron, 2023 © Philippe Biolato