Johan Creten: Strangers Welcome is on view at Perrotin, New York

June 1 – July 26, 2024

Perrotin is pleased to announce Strangers Welcome, a continuation of Johan Creten’s exhibition Le Coeur qui déborde (The Overflowing Heart) at the remote Abbaye de Beaulieu-en-Rouergue in France. The Paris-based sculptor will introduce his colorful, mysterious creations and gilded bas-reliefs to New York, presenting viewers with his eclectic metaphors on the human condition.

The following is an essay written by Dr. Leigh Arnold, Curator at the Nasher Sculpture Center, for Johan Creten’s newest catalogue titled Strangers Welcome, released concurrent to the opening of his exhibition at Perrotin New York.

A large white whale in the middle of a green sea.

Johan Creten’s description of the setting for his 2023 solo exhibition Le Coeur qui déborde (The Overflowing Heart) at the Abbaye de Beaulieu-en-Rouergue poetically references the unadorned Romanesque architecture of the 12th-century Cistercian abbey (notably, the white stone that comprises it) and the lush forest surrounding it, and effectively sets the scene for his “oceanic” exhibition of recent ceramic, resin, and bronze sculptures. In literature, the “white whale” refers to the central antagonist of Herman Melville’s 1851 epic novel, Moby-Dick, which follows a sea captain’s obsessive quest for vengeance against the natural instincts of a colossal leviathan. In the years since Moby-Dick’s publishing, the “white whale” has become synonymous with an obsession that is relentlessly pursued. Such could describe Creten’s own efforts to elevate ceramics to the level of “high art” within the realm of contemporary sculpture—a pursuit he took up nearly 40 years ago. Trained as a painter, Creten’s interest in clay began when he discovered an abandoned ceramics studio as a student at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent in the 1980s.

“I chose ceramics also because nobody else was working with this material,” Creten explained. “There is a place to take ceramics, there is a history to write with this material. You can express things. You can talk about politics. You can talk about the world. You can talk about yourself.” Creten continues to chip away at the stale hierarchies that often denigrate media associated with use value or craft, like clay—an inexpensive and messy material that requires hands and labor to manipulate (rather than the “clean” ideas of conceptual art that are manipulated by the mind). Renouncing popular taste and trend, Creten’s sculptures are a feast for the eyes, with their gestural, virtuosic glazes and sumptuous surfaces that also light up the mind with their enigmatic and inscrutable references. Creten challenges his viewers to embark on their own individual quest for meaning and interpretation.

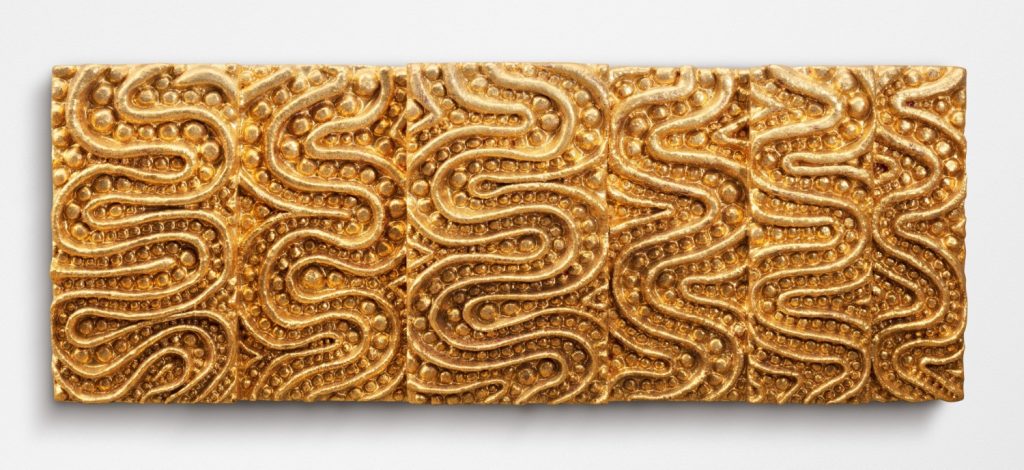

Returning to the “oceanic” metaphor that permeates Le Coeur qui déborde (The Overflowing Heart): throughout the nave of the church, sea beasts—cheeky mermaids, sinful sirens, and seahorses undergoing metamorphosis—perched on color coded ceramic socles, while gleaming gold bas-reliefs containing abstract patterns evocative of mollusks, oyster shells, snakes, or eels lined the walls of the damp and dark cellar. Within this motif, Creten exploits a play on words to great effect: the French homonyms la mer / la mère: the sea and the mother become the artist’s protagonists. Personifications of the sea as feminine abound in literature and poetry that symbolically link the seas and ocean to creation, fertility, and mystery, but also to chaos, tempestuousness, and irrationality. Through this lens, the patterns on Creten’s gold bas-relief sculptures begin to take on forms of female sexual anatomy and remind us of another play on words: in French, “la moule” (mussel) is vulgar slang for vagina. The ambiguity in these wall-based works—are they representations of la mer or la mère? —is a leitmotif found in many of the artist’s sculptures, from the Odore di Femmina series, first shown in 1991, to his series of Waves for Palissy, begun in 2004, to the more recent bas-relief sculptures Relief IV (2012) or Vulva (2017).

Creten installed the Éloge de l’ombre bas-reliefs at the same elevation along the cellar walls, creating a ribbon of gold or a lustrous frieze of shimmering patterns that situates them in the realm of architectural adornment. In the context of a religious setting, gold evokes illuminated manuscripts, the halos of saints in Eastern Orthodox icons, or chalices used in the Eucharist, but here it was a stark addition given the vows of piety, poverty, and adornment the monks inhabiting this Cistercian monastery would have followed. These works also functioned to bring light into the dark cellar through their reflective surfaces. Creten purposely left this space unlit to further dramatize subtle lighting on the variegated surfaces. This strategy refers to the writings of Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (Japanese, 1886-1965), whose 1933 essay, “In Praise of Shadows” (éloge de l’ombre in French) argues that the power of beauty resides in shadow and subtlety, rather than total illumination. By limiting the lighting, Creten further emphasized the many shadows in each work, referencing taboo subjects or the many holes and crevices of the human body that can be used for sexual pleasure (a hole is a hole is a hole).

Intriguingly, a single work from this series, Nr 13 (2022-23), was inset in an alcove just outside the cellar and oriented vertically, with its long sides running parallel to the walls. Unlike others from Éloge de l’ombre that are dense with patterns and lines, Nr 13 contains only three elements: two tubes on either long side, with a sphere nestled in the center. As installed in the Abbaye, the bas-relief becomes a kind of threshold, with the long tubular forms pushed aside or opened by the ball between them. In this vertical orientation it also recalls Jasper Johns’s 1958 encaustic Grey Painting with Ball in which “the upright dimension is given by a gash in the canvas, pried and held open by an intruding ball.” Johns used wooden balls in several paintings of that period to critique the masculinity typically associated with Abstract Expressionism and the notion that a painting need have “balls” to be successful. Notably Johns came up one short of typical male anatomy with Grey Painting with Ball. While Creten’s Éloge de l’ombre – Nr 13 formally resembles Johns’s painting, in the context of the surrounding bas-reliefs from the series, with their labia-like patterns and the overarching theme of the sea, the sculpture becomes representative of anatomy of the opposite sex— the slit or “gash” (each slang for vagina) formed by two tubes becomes a point of creation and mystery. Rotating the sculpture’s orientation by 90 degrees, in line with others in the series, generates even further interpretations, transforming the gleaming central sphere into an enormous pearl in the mouth of a mussel or oyster, or an eye. In that sense, the work echoes Georges Bataille’s 1928 novella Story of the Eye (l’histoire de l’œil in French), a pornographic fantasy of two lovers delving into the world of sexual fetishes and deviancy. Roland Barthes would later go on to theorize about the centrality of the eye in Bataille’s novel and its interchangeability with testicles, eggs, and other ocular objects throughout.

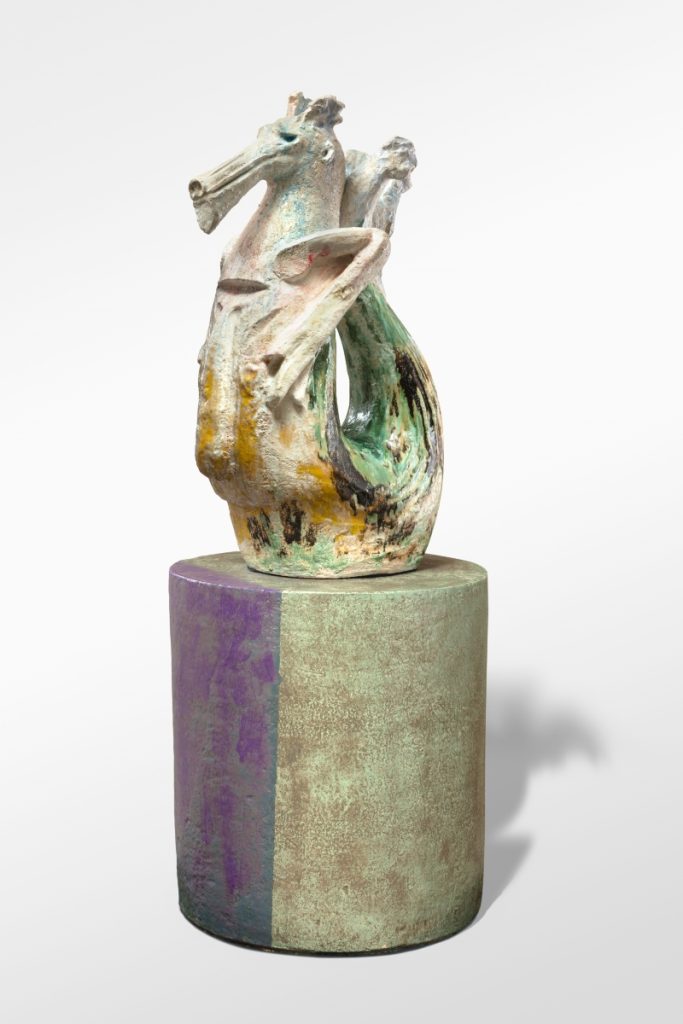

Moving into the nave of the church, the bestiary Creten created for his 2022 exhibition at La Piscine – musée d’art et d’industrie André Diligent de Roubaix continues with new humanoid aquatic creatures. La sirène effrontée (the naughty mermaid) and bronze La Laguna (a reference to Venice, the floating city), each feature female-coded effigies holding postures reminiscent of the Madonna in prayer. Installed around these seemingly pious characters were sculptures resembling seahorses undergoing metamorphosis to something otherworldly or hybrid in form. Their arms and hands—in some cases talon-like, while in others webbed like fish fins—ape the piety displayed by the mermaids, hinting at their true nature as beguiling and dangerous sea nymphs. In medieval bestiaries, the siren was an enchantress, who seduced, entrapped, and killed incautious and unmindful men through their propensity for causing shipwrecks. In the context of La Coeur qui déborde (The Overflowing Heart), these figures relate to ideas of sin, temptation, and the lurking dead.

A sense of violence permeates many of Creten’s seahorse hybrids, as exemplified best in The Sex Addict, Pump and Dump / Satyriasis (2021-23). Featuring a kind of sea satyr resting on a socle glazed in the primary colors of red, yellow, and blue, the entire composition appears to be bleeding from a deep wound at the head or neck of the beast. Red and black glazes gush down its sides in homage to the gesture so emphatic in Abstract Expressionist painting. Even the pedestal’s colors bleed, with red dripping into the yellow band. Its title reads like a short poem that breaks down in three parts referencing a form of securities fraud or financial trickery—pumping up a stock price, only to dump it to reap the artificial rewards to the detriment of the economy—bookended by colloquial and pathological terms for sexual addiction. Altogether, The Sex Addict, Pump and Dump / Satyriasis references the type of creature Creten sculpted: a mischievous male spirit with an insatiable sexual appetite.

Scattered throughout all the spaces were ceramics from Creten’s Observation Points series of hybrid sculptures / stools / pedestals, that resemble traditional bases used to display sculpture and function as seating for gallery visitors. Creten strategically installed these works to correlate to different viewpoints. He also considers the number of Observation Points in any given space and how that will affect the dynamic and experience of his viewers: with one, there is observation; with two, there is dialogue; with three or more, there is a crowd, and so on. Their portability as stools that can simply be picked up and moved, along with their flag-like appearance, transform these objects into symbols of universal migration.

In contrast to previous installations of Observation Points, the Bestiarium at Roubaix for example, the colors for those installed in the Abbaye were much more discreet, in keeping with the architecture and design of the Cistercian monastery. Creten’s previous Observation Points were glazed with bright primary colors commonly found at the circus: reds and yellows; bright pinks and blues. In contrast, Cirque 10, for example, is almost monochrome, with alternating shades of pale and grey blues recalling the iconography of Jasper Johns, whether the stars from his iconic Flag paintings or the lesser-known sculpture from 1958, while also referring to the six-pointed star in the nave of the abbey. Creten’s more subdued color palate for the observation points there suggest that this is not a place of whimsy or folly, but rather a place for somber reflection and appreciation.

Creten’s Le Coeur qui déborde (The Oveflowing Heart) continues in part at Perrotin New York as Strangers Welcome in June 2024, in a markedly different space: the “neutral” white cube gallery. Transposing the exhibition from one heart to another: the heart of one of the most remote places in France to that of the bustling contemporary art scene fulfills Creten’s desire to share these works with a wider audience (i.e., to welcome strangers to his most recent oeuvre) and in many ways further solidifies his place among the ranks of contemporary sculptors. Returning to the Moby-Dick reference that opened this essay, if Creten’s “white whale” is synonymous with the “white cube” of the contemporary art scene, it would seem he has caught it. The hybrid sculptures that populate both exhibitions—sea beasts or humans, pedestals (for display or performance) or seating (for observation or contemplation)—draw analogies to the human condition and all the dualities contained within it: sacred and secular, pious and sinful, beautiful and grotesque.

Johan Creten was born in 1963 in Sint-Truiden, Belgium, and now lives and works in Paris, France. Frontrunner in the revival of ceramics in contemporary art, the Paris-based artist Johan Creten has been working on the move for almost forty years, from Mexico to Rome, from Miami to The Hague.

With his innovative use of ceramics, he started working with clay in the late 1980s, when the medium was still seen as taboo in the contemporary art world. Famous for his allegorical sculptures in ceramic and bronze, Johan Creten continues since the 90’s his representations of a world full of poetry, lyricism and mysteries. They underline the importance of beauty in his work, while reaffirming his humanist consciousness and the social and political resonance of his practice. In his creative process, Johan Creten mentions “slow art” and the need for a return to introspection and exploration of the world with its individual and societal torments.

Contact

newyork@perrotin.com

Perrotin

130 Orchard Street

New York, NY 10002

United States

Captions

- Installation views of ‘Strangers Welcome’ (2024). Photographer: Guillaume Ziccarelli. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, Éloge de l’ombre – Nr 5, 2022 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, gold luster, 17 x 43 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, Éloge de l’ombre – Nr 11, 2022 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, gold luster, 17 x 43 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, The Closet Vegan, 2021 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, 84 x 30 x 24 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, The Dealer Blue Eye – Red Eye, 2021 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, 82 x 30 x 32 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, Gigolo Falling off a cliff, 2021 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, 84 x 30 x 34 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

- Johan Creten, The Sex Addict, Pump and Dump / Satyriasis, 2021 – 2023, Glazed stoneware, 81 x 30 x 39 inch. Photographer: UNKNOWN. ©Johan Creten / ADAGP, Paris & ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.