October 7, 2023 – February 25, 2024

Artists: Aarti Vir, Adil Writer, Dipalee Daroz, Ela Mukherjee, Keshari Nandan Prasad, L N Tallur, Madhur Sen, Manjunath Kamath, Mudita Bhandari, Neha Kudchadkar, P R Daroz, Ray Meeker, Reyaz Badaruddin, Shampa Shah, Shirley Bhatnagar & Pallavi Arora, Supriya Menin Meneghetti, Trupti Patel

Curator: Kristine Michael, India

Drawing parallels between India’s rich cultural and philosophical traditions and the Korean cultural heritage and spiritual foundations, this significant exhibition at Clay Arch Gimhae Museum takes ceramics as the unifying creative medium that holds immense cultural, historical, and artistic significance in both countries. Clay has played a significant role in both cultures, as utilitarian objects and as items of aesthetic, ritual, festive and symbolic value. The tradition of making in clay has continued to evolve and contemporary ceramic artists blend traditional techniques with modern artistic expressions, ensuring the continuity of this ancient craft. They serve as a testament to the craftsmanship and artistic sensibility of artists throughout the ages, and they continue to be cherished as both functional objects and works of art.

India is a site where the past and present intersect in fragmented refractions. We live in a space where there are worlds together revealing the hidden connections and contradictions and worlds apart, that anticipate the future which we are moving towards with lightning speed aided by technology and globalization. This exhibition shows artistic engagement that ties in the historical past and present with specific body of works through the lens of the artists’ own lived experience or collective cultural memory. This serves as a source of inspiration in both visual and material ways in order to make visible traces of the past, often lost, displaced or counter to the dominant narratives.

Ceramics in India itself is often considered the ‘unarchived’ and ‘unrecorded’ in modernism, the forgotten primary material in the advent of new materials and technology, the marginalized narrative of an entire hereditary craft in the colonial categorisation of fine art versus craft.

The artists in ‘Multiple Realities’ each reflect on their use of the medium and their own practice from the perspective of ceramics in the 21st century not as a static entity, but one that is in a constant state of flux or transformation. Their works are not simply a question of preserving the past, but instead a challenge to rethink and reimagine the role of ceramics in shaping the cultural memory and history in the future. The voices of artistic practice seen here is defined by the past, represented in the present and anticipate the future.

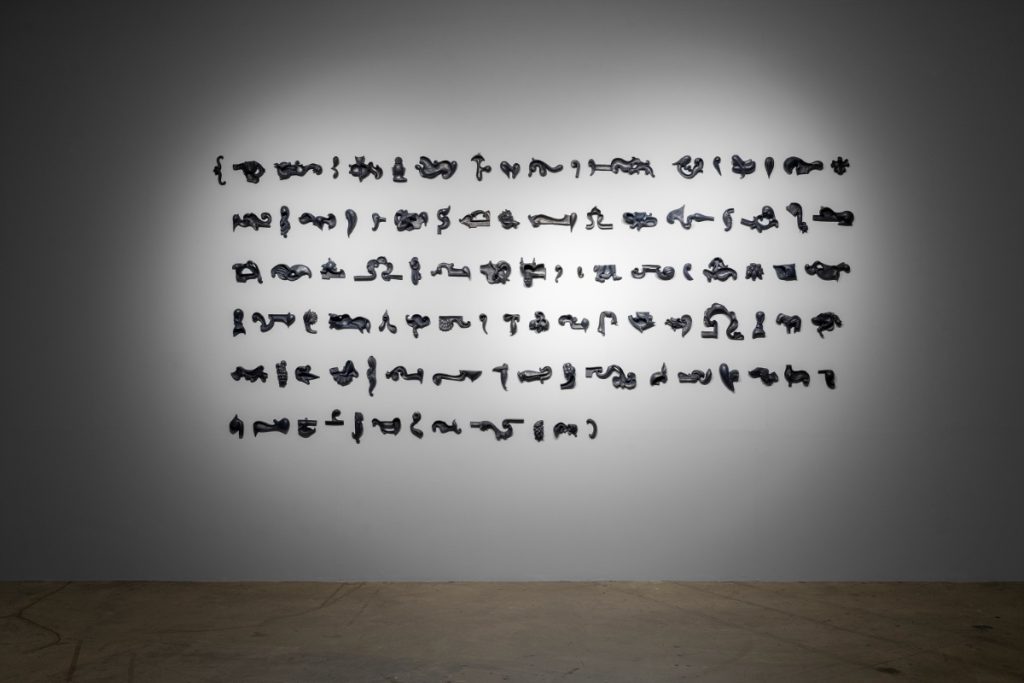

Manjunath Kamath’s relief-sculptural installation ‘Private Poem’ consists of 127 small pieces of terracotta sculpture arranged on the wall in six or seven rows, which look like text – somewhat like the ancient hieroglyphics – when viewed from a distance. On closer perusal, the individual pieces are revealed to be fragments of classical and traditional Indian sculpture and temple architecture.

Suspended between the past and the future, Daroz’s architectural gateways provide a unique sensory experience set out in space and time. The threshold marks an invasion as well as an intimate experience of a space that is both personal and public. The portal invokes resonances of the Buddhist stupas that act as transitions between old and new: gouged out with memories both of pain, delight and longing, they entice the viewer to reconsider a new age with the impulse to live anew. They are witness to the times, serving as a testimony to past lives and societies. Fossil like forms embedded in the recesses remind one again of being carriers of cyclical time.

Trupti Patel responds through her sculptures and installation to the story of Heo Hwang-ok that represents the enduring cultural and historical bonds between Korea and India and serves as a reminder of the shared heritage of these two nations.

Aarti Vir’s Shadow Crossing references the Indian myth of the tyrannical asura Hiranyakashipu, who cannot be destroyed by weapon, man or beast, neither during the day or night, nor indoors or out. He meets his death at the hands of Narasimha, half-man half-lion avatar of Lord Vishnu who dismembers him – with his claws, on a threshold, at dusk. The life-size doorways invite visitors to walk through. As each threshold is breached, the viewer will pass into a space and substance that either physically challenges or provokes the senses, with the intent to encourage reflection upon those often-unnoticed spaces, with their potential for transformation, resurrection or dissolution.

Ela Mukherjee’s Meanderings is an installation based on her experience of the pandemic lock down in Delhi. It consists of approximately 125 pieces and spans in a spiral of 7 ft diameter. The work is a repetitive sequencing with separate smaller elements to form a large cohesive sculptural installation. The minimal drawings on each of these records her daily experience of the period on abstract terms.

Neha Kudchadkar’s Weightlifter, a moving image work, is part of a recurring project – Auto Ethnography Through Objects – which marks Kudchadkar’s body in the socio-political space it occupies through objects, at different points of her life. Weightlifter documents a difficult, precarious, uncomfortable moment in time, made heavy by grief, breakdowns, depression and helplessness. Made during the pandemic, it records the guilt and struggle of breathing as a world collapses around her.

Often, in Kudchadkar’s work, the focus is the body. The actor. The acted upon. She explores the body as object. As a tool for the making as well as the experience of objects. The objects tell stories of their making, stories (and secrets) of the body. The body has often been likened to clay. The body as ‘that which has emerged from the earth and that will eventually become one with it’.

Madhur Sen’s art not only has the potential to create meaningful and thought-provoking visual experiences but also to advocate for positive change and social justice. By portraying the daily wage workers of India and their struggles, Sen is contributing to a broader dialogue about the importance of fair wages, labor rights, and social equity. Her work is a powerful testament to the resilience and strength of these individuals who play a vital role in society. Through her art, she humanizes the daily wage workers, giving them a face and a story which helps the audience to empathize with their struggles and recognize their dignity and humanity. It documents a part of Indian society that is often invisible or ignored, preserving their stories for future generations.

Filmmaker Pallavi Arora and Ceramic artist Shirley Bhatnagar explore the idea of loss and creation through the medium of clay. Engaging with artifacts unearthed from the oldest Indus Valley Sites from figural to anthropomorphic works the duo have combined animation and drawings to make a lyrical and experimental film.

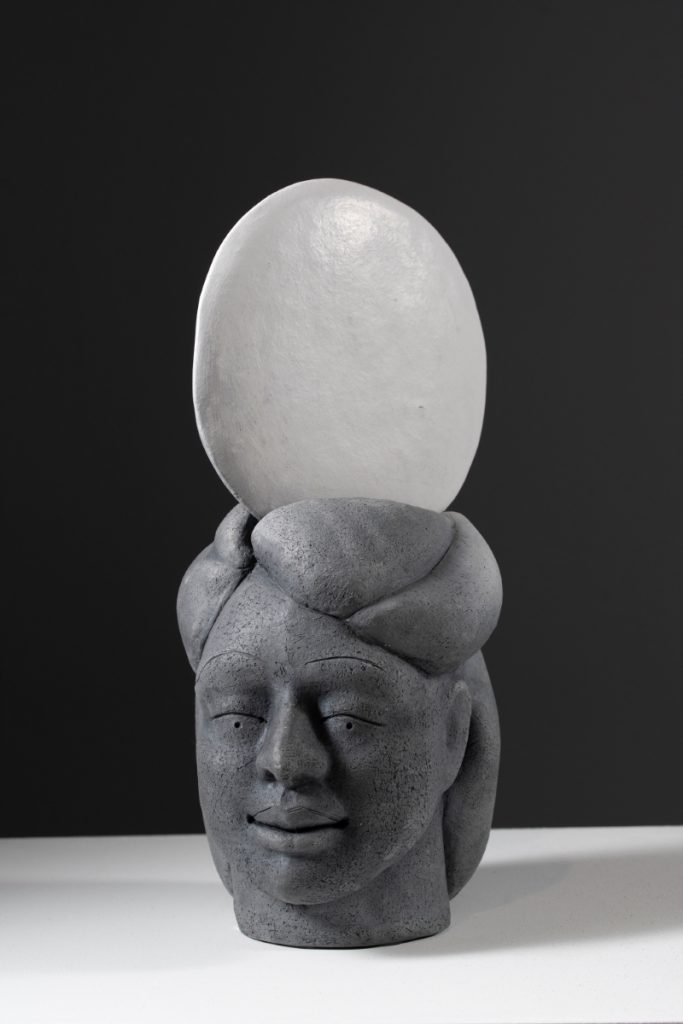

The complicated exchanges between the legacies of cultural imperialism and the ever-increasing popularity of yoga around the world today attest to an inverse dynamic of colonialism. Tallur’s installation is based upon a strange confluence in India’s colonial history. Two hundred years ago, Christian missionaries from Basel opened a tile factory in the coastal town of Mangalore in the southern Indian state of Karnataka (where L.N. Tallur was raised and continues to live part-time). While drawing a connection between Hatha Yoga, the representations of colonial subjects for museological displays, and the gruelling experience of the missionaries during their time in India, Tallur’s sculpture also reflects upon some of the more absurd manifestations of human endeavour.

Contact

info@clayarch.org

The ClayArch Gimhae Museum

275-51 Jillye-ro, Jillye-myeon

Gimhae-si, Gyeongsangnam-do

South Korea

Photos Courtesy ClayArch Gimhae Museum