O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell is on view at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville

February 22 – June 15, 2025

O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell, an exhibition on view through June 15, 2025 at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, features 20 works by Jody Folwell (b. 1942), a contemporary potter from Kha’p’o Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico). The exhibition centers Folwell’s practice and situates her within the intersecting artistic contexts of Kha’p’o Owingeh, Native American art, and contemporary and American art more broadly.

Folwell has revolutionized contemporary Pueblo pottery, and Native art more generally, by pushing the boundaries of form, content, and design. She was the first Pueblo artist to employ writing and designs as personal, political, and social narratives on her pottery. Widely considered among the most significant and influential clay artists of her generation, O’ Powa O’ Meng (“I came here, I got here, I’m still going” in the artist’s Tewa language) explores the breadth of her groundbreaking career and demonstrates the arc of her artistic development. Works by Folwell’s mother, Rose Naranjo, daughters, Susan Folwell and Polly Rose Folwell, and granddaughter, Kaa Folwell, are also featured.

To see Folwell’s art is to encounter the unexpected. Folwell possesses an extraordinary and unique artistic vision that builds upon traditional Pueblo pottery techniques while pushing beyond these established styles into the realm of groundbreaking art. Throughout an artistic career that spans five decades, she has consistently reached for new horizons. Her avant-garde choices of forms, content, and designs have inspired and influenced younger generations of Pueblo potters. This retrospective exhibition presents iconic works offering new knowledge about her practice and inspirations and enable meaningful encounters with her pottery. A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition with essays and personal reflections by Folwell’s longtime artistic peers, friends, and family members.

Folwell lives and works in Kha’p’o Owingeh (“The Place of the Singing Water”), the small village where she was born and raised. Known more commonly to outsiders as Santa Clara Pueblo, it is one of six Tewa-speaking Indigenous villages in northern New Mexico. These Pueblo communities have an ancestral and continuous tradition of pottery-making that extends at least two thousand years. Folwell grew up at a time when pottery was everywhere; it was used for storing food and water, for cooking, as gifts, and as an economic tool. The pots made and used by her family inspired her as a child and provided a source of both grounding and creativity.

In the early 1970s, Folwell changed the course of her life by devoting herself to creating pottery full-time. She mastered the arduous and complex traditional methods of harvesting and processing clay; of hand-building, slipping, and polishing pots; and of firing the vessels, to give shape to her own vision. In a community full of expert potters who had spent decades honing their craft and were recognized by the Native art market, she needed—and wanted—to do something different from the established, now-canonical black and red forms of Kha’p’o Owingeh pottery. Folwell created a bold new work titled Half a Step (Buffalo-Wolves) (1975) where she used a palette knife to sculpt racing buffalo figures onto the surface of a traditional redware ceramic jar. This middle register’s un-slipped and unpolished clay, laid bare for the viewer to see within a beautifully sculpted and finished vessel, was Folwell’s innovation. It was her first entry into the storied annual Santa Fe Indian Market held by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA). Susan Folwell commented that her mother “had never seen anybody do that before, and certainly not in any of the Pueblos.”

In 1984, Folwell submitted another one of her works for competition in the Santa Fe Indian Market. Competition judges could not find a category that fit her entry titled The Hero Pot (1984), a green pot with human and horse figures painted onto the surface. It was a stark departure from the competing traditional black pots and won the competition. This single vessel—which is today considered to represent what a Pueblo pot can look like—marked the beginning of an artistic revolution in both Pueblo pottery and Native art history.

“It became a really interesting period of time for me because it was total experimentation in a different direction, and it wasn’t something that had been handed down for generations,” Folwell said. She kept elements of traditional pottery even when she was experimenting with her artwork, always starting with the basics to remember those original uses for everyday life. “If it becomes very contemporary, it still has to have that sense of tradition, the culture, this spiritualness of the piece,” Folwell said.

When discussing her personal journey and artistic career, Folwell uses the Tewa phrase “o’ powa o’ meng”: O’ powa is “I came”—as in, I came when I started making pottery. Life was really contorted for me during that period and once I started working in pottery, it was like I came, I found myself. I was able to find some kind of peace and comfort and focus because I was doing something that I was happy with. And o’ meng is ’I’m going forward’—I’m going to be focused. The Clay Spirit gave me the ability to move forward and become something or somebody that it wanted me to be. So that’s what the words ‘o’ powa o’ meng’ mean to me. I came home. It is about a life’s path; that’s the closest idea. My path was set for me. Even now, I’m just halfway home. And when I’m sitting here looking back on it, then I’m saying to myself, O’ powa o’ meng—I came here, I got here, I’m still going.”

For more than fifty years, Folwell has remained committed to the vessel form as the place for her boundless innovations. Through her pots, this exhibition reveals a daring artist who is continually experimenting with novel technical approaches, shapes, sizes, firing methods, and materials. She fearlessly uses pottery as a platform for political and social commentary—acts that were seen as radical when she started, and which are now emulated by younger artists. Her vessels also include visual metaphors for personal experiences and biographical narratives of her relations, both human and animal.

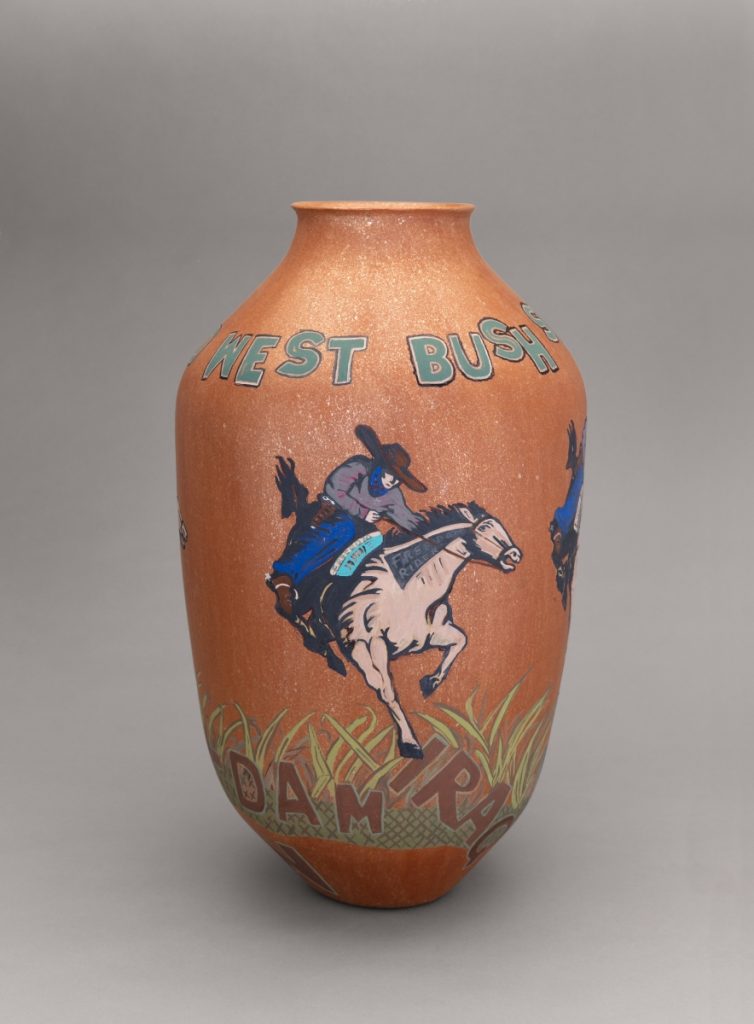

Among the works on display is T’ah p-ah sa’ wae (Dad’s Fish) (circa 2000), a jar that was inspired by childhood memories of the artist’s father’s love of fishing. In Wild West Show (1996–2003), Folwell painted the Western-comics style scene on a jar in response to events after 9/11 where she depicts President George W. Bush as a modern cowboy on horseback, eager for war. Her Wild West imagery speaks to American occupation of lands both abroad and at home. Roober Stampede (1990) is an ironic observation of the Native art market itself, with a mad dash of horses representing pottery collectors vying for award-winning pieces. Folwell replicated the style of prehistoric European cave paintings to convey the beginnings of art and humanity in Ancient (2018 or 2019).

One of Folwell’s favorite pieces in the exhibition is Lucky’s Conch (1990) a pot shaped like a conch shell that she wanted to resemble a shell that could be picked up and blown into like a horn. “I have chosen to feel that the shell pot was used to call someone and to call people to the pottery world,” Folwell said.

Folwell’s artistic influence is also evident in the work on display done by her daughters and granddaughter. All three carry forward her practice of creating provocative narrative vessels. The creative process embodied within o’ powa o’ meng has allowed Folwell a path of endless innovation. Pulled by a creative force, she is in a perpetual state of becoming herself—and discovering herself—through her artmaking. Always intensely curious, Folwell is on a personal and artistic journey that has brought her to the present moment. She’s here, she has arrived, and she is still going.

O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell is organized by The Fralin Museum of Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The exhibition is co-curated by Adriana Greci Green, Ph.D., Curator of Indigenous Arts of the Americas at The Fralin Museum of Art; Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Ph.D., Curator, Cafesjian Art Trust Museum, Shoreview, Minnesota; and, Bruce Bernstein, Senior Scholar, School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

This article is based on text from the exhibition catalog by co-curators Adriana Greci Green, Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Bruce Bernstein.

Contact

info@uvafralinartmuseum.virginia.edu

The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia

155 Rugby Road

Charlottesville, VA 22904

United States

Captions

- Jody Folwell, Buffalo Soldier, 2023. Clay, paint. Pot: 15 x 14 in.; five tiles: 12 x 12 in., 10 x 10 in., 8 x 8 in., 6 x 6 in., 4 x 4 in.; ten balls, each approx. 2 1/2–3 in. Tia Collection. Photo by Addison Doty © Jody Folwell

- Jody Folwell with Bob Haozous (Chiricahua Apache, b. 1943), The Hero Pot, 1984. Clay, paint. 10 x 9 1/2 in. Wilshin Family Collection, Scottsdale, Ariz. Photo by Kelso Meyer © Jody Folwell

- Jody Folwell, Wild West Show, 1996–2003. Clay, paint. 21 7/16 x 14 1/16 in. Courtesy of the School of Advanced Research, cat. no. SAR.2004-16-1. Photo by Addison Doty © Jody Folwell

- Jody Folwell, Lucky’s Conch, c. 1990. Clay. 12 1/4 x 7 1/2 in. Heard Museum Collection, Phoenix, Ariz. Gift of Neil and Sarah Berman, 4391-8. Photo by Craig Smith © Jody Folwell

- Installation views, O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, 2025. Photos: Stacey Evans Photography