Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled, 2004, Porcelain, 6 1/4 x 10 x 5 1/2 inches (15.9 x 25.4 x 14 cm)

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled, 2000, Porcelain, 9 3/4 x 9 5/8 x 3 3/8 inches (24.8 x 24.4 x 8.6 cm)

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled, 1994, Porcelain, 4 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 4 inches (11.4 x 16.5 x 10.2 cm)

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled (Horn Series), 2000, Porcelain, 22 1/2 x 9 x 18 inches (57.2 x 22.9 x 45.7 cm), Signed “R”

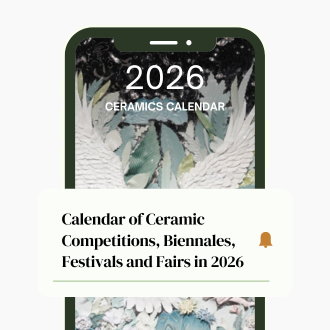

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled (wall sculpture), 2008, Porcelain, 18 x 17 x 9 1/4 inches (45.7 x 43.2 x 23.5 cm)

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled (wall sculpture), 2009, Porcelain, 9 x 8 7/8 x 4 inches (22.9 x 22.5 x 10.2 cm)

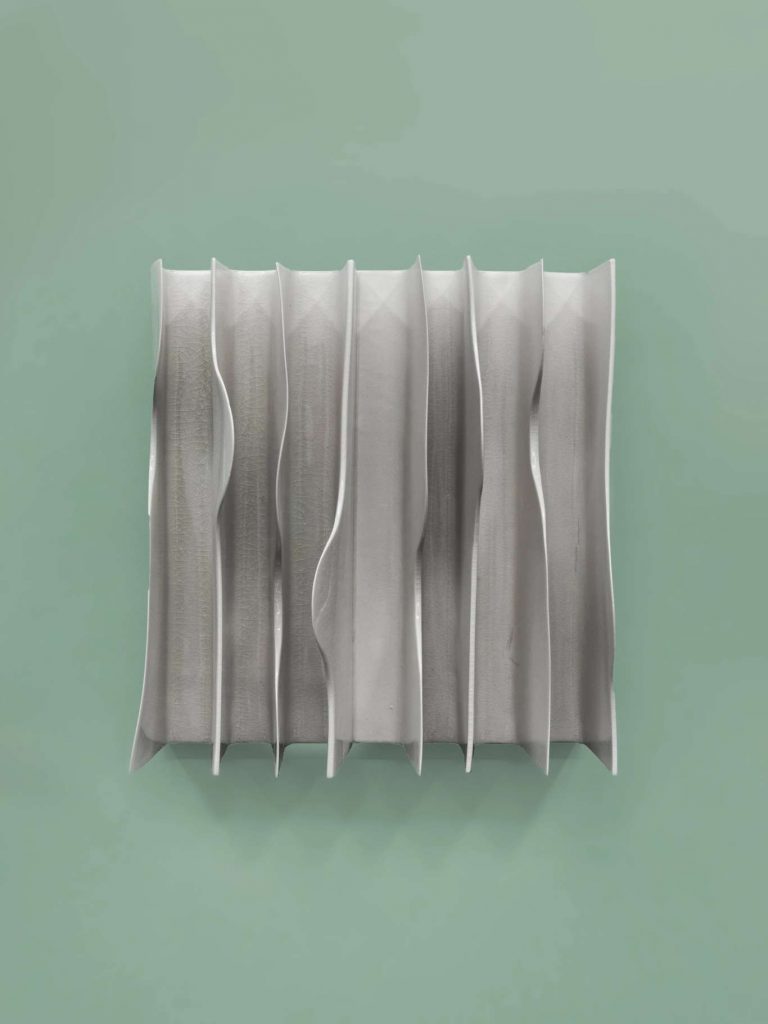

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled (Mama Pot), 1975, Hand-built stoneware, oxide colors, reduction fired, 18 x 21 x 23 inches (45.7 x 53.3 x 58.4 cm)

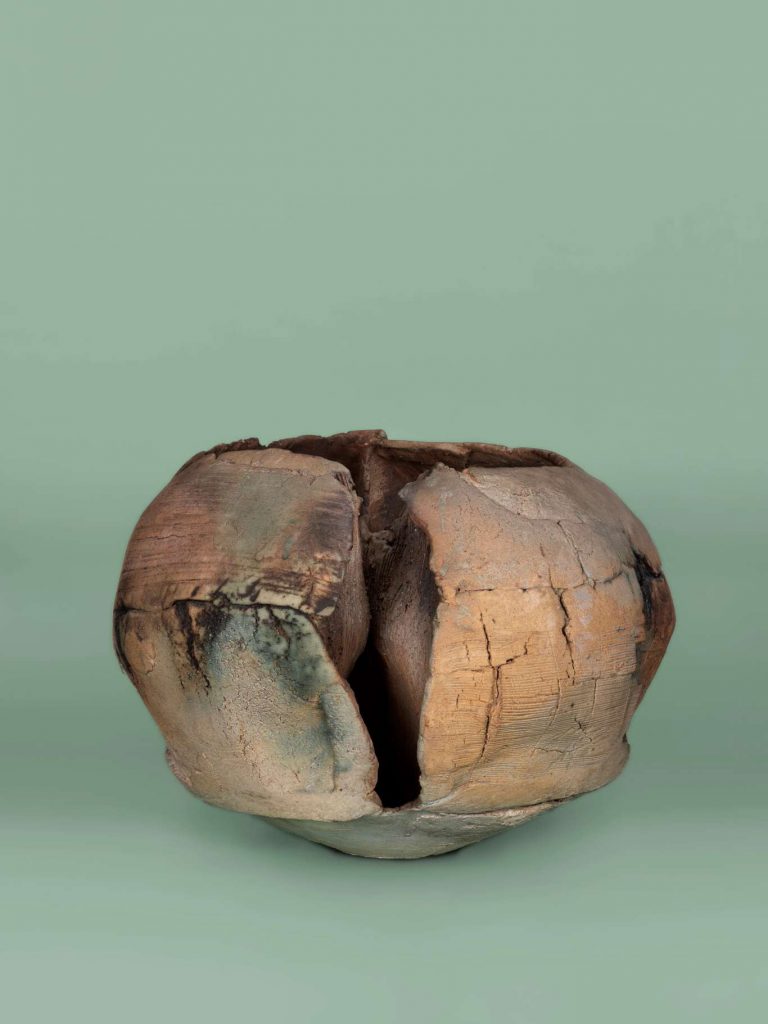

Estate of Ruth Duckworth, Untitled (Mama Pot), 1980, Hand-built stoneware, oxide colors, reduction fired, 11 x 12 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches (27.9 x 31.8 x 29.2 cm)

She’s Clay, sculptures from the Estate of Ruth Duckworth at Salon 94, New York

June 30 – September 11, 2021

Ruth Duckworth (1919–2009) was a lifelong outsider: a woman artist, a Jew born in Germany, and an immigrant, first to Britain as a child and then to the U.S as an adult. It is no surprise, then, that when she had a choice about whether to follow dominant trends or to stand outside them, she chose the latter. In choosing clay as her medium she doubled-down on her outsider status. Her use of clay to make sculpture was seen as a conceptual impossibility in the field in the late 20th century, preventing her work from receiving the critical understanding it deserves.

Born in Hamburg in 1919, Ruth Windmüller Duckworth emigrated to England in 1936, where she built a career as a ceramicist during the post-war period. As a young artist in the forties and fifties, she struggled like so many others, working as a tombstone cutter, button-maker, and puppeteer, trying several art schools before finally graduating from the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Together with fellow refugees Hans Coper and Lucy Rie, she became known for British Studio Pottery, non-functional ceramics combining Eastern and Western influences. The great modernist sculptors Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, and Constantin Brancusi influenced her work. They were all adapting natural forms into abstract sculptural languages, but only Duckworth was doing it with clay.

In 1964 at the invitation of the University of Chicago, Duckworth immigrated to the U.S. to teach ceramics at Midway Studios. In 1966, she had her first one-person exhibition in the U.S. at the Renaissance Society, where she attracted the attention of Julian Goldsmith, Dean of Geophysical Sciences. Dean Goldsmith, an avid collector of Pre- Columbian ceramics, commissioned the artist to create a ceramic installation for the Brutalist Hines Geophysical Laboratory, then under construction. During this period, the university underwent a Brutalist building boom, with notable and rare enthusiasm for avant-garde art and architecture.

Dean Goldsmith wrote a letter to alumni about the incomplete atrium project in 1966: “As one walks into the building, he will pass through its essence. […] I think it will be stunning, for not only do I consider Mrs. Duckworth to be one of the world’s leading art-ceramicists, but she has spent a great deal of time prowling in our library and looking at rocks, minerals, landscapes, waves and weather, on our behalf.” Duckworth’s immersion in the burgeoning field of geomorphology at UChicago, especially in novel satellite images of the earth, as well as its geophysical collections, transformed her work, and led to the creation of not only the groundbreaking Earth, Water, Sky in the Hines Atrium, but also to her masterpiece, Clouds Over Lake Michigan, as well as a huge range of vessels, murals, and sculptures made from earthenware and porcelain.

In fact, the effect of this experience on Duckworth was so profound that she herself referred to her pre- and post-geomorphology periods. Geomorphological traces are particularly visible in the earthenware works, both wall works and vessels, from the 1970s. But over time, the ridges and craters become more abstract and less connected to the landscape, and the forms shift from earthenware to porcelain. The chunky ridges become nearly translucent fins (sometimes inverting into slits and slots in the vessels), the craters become perfect hemispheres (both convex and concave), and the palette fades from rich earthy browns and azure glazes to the faintest pastel tints. Her later works, especially the “cups and blades,” are as refined as any Robert Irwin projection, but they maintain the visual vocabulary she first developed in the late 1960s.

Despite the fact that this remarkable development in her work over time has not received the critical attention that it merits, the last decade has seen both a burgeoning of art historical interest in previously overlooked women modernists and a reconsideration of so-called “craft media,” such as ceramics, in the field of sculpture. Lee Bontecou, Judy Chicago, Gego, and Ruth Asawa are just a few of Duckworth’s contemporaries whose oeuvres have benefitted from recent scholarly attention. A 2015 exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery, The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art, proposed a bold reconsideration of the medium within the terms of modernist sculpture and foregrounded her work. Duckworth’s career is ripe for examination within these novel rubrics.

In 1974, impressed by Earth, Water, Sky, the Dresdner Bank commissioned Duckworth to make a monumental ceramic mural for their flagship office in Chicago, which was completed in 1976. When the Dresdner Bank closed its Chicago office in 1984, Clouds Over Lake Michigan was purchased by the Chicago Board of Options Exchange and moved to the lobby of its LaSalle Street headquarters where it remains today. The work is 9’ high and nearly 30’ long, comprised of 65 ceramic tiles in high relief, set in mortar on a wall.

Clouds Over Lake Michigan is a majestic work, fluidly blending representation and abstraction, with an aerial view of the southern tip of Lake Michigan and its watershed as its origin point. Bright blue glazes on the lake and rivers meet the warm colors of rocks and earth. The static grid formed by the tiles counters the flow of dynamic organic shapes welling up out of the surface, a technique Duckworth pioneered in the Hines Atrium. Meteorological, geological, and geographic features are interspersed with imaginary archaeological traces. In its deployment of ceramics, and as a breathtaking evocation of the grandeur of the region, the work is peerless. (This is one of the first landscapes ever made from the high vantage afforded by then-novel satellite views of the earth, which played a galvanizing role in the environmentalist movement.)

This exhibition represents the beginning of a new research initiative into Duckworth’s oeuvre, a new consideration of her work within environmental, feminist, and sculptural terms. In the vessels, wall murals, and sculptural objects included here, we find further developments and refinements of geomorphological interests that reveal a burgeoning environmental awareness not dissimilar to Robert Smithson and other Land Artists working at the same time, though expressed in formally dissimilar ways. We can also see the bulges, concavities, and clefts that typify the work of women abstractionists of the late twentieth century, which call out for further investigation. Duckworth referred to her work as ceramic sculpture, inviting a consideration of her work within terms that grew out of the nature-based practice of her heroes Moore, Noguchi, and Brancusi, whose influence is clear. Her career flourished in the late 20th and early 21st century, and she exhibited widely on the East Coast and in Europe.

Finally, more than fifty years since Duckworth arrived in the U.S., art history is catching up to her, and the full range of her remarkable career can be understood.

Text by Laura Steward

Contact

info@salon94.com

212.979.0001

Address

3 E 89th Street

New York, NY 10128

United States

Photos by Dan Bradica. Courtesy of the Estate of Ruth Duckworth and Salon 94, New York.