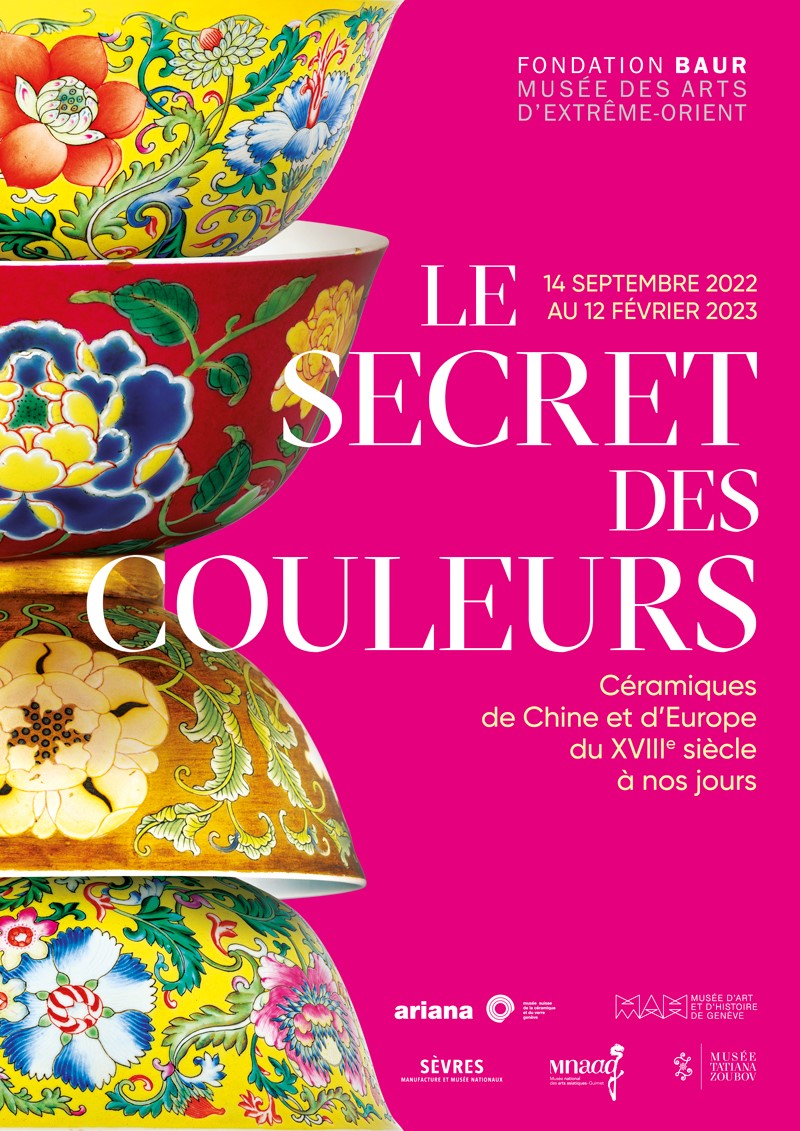

The Secret of Colours: Ceramics in China and Europe from the Eighteenth Century to the Present is on view at Fondation Baur – Museum of Far Eastern Art, Geneva

September 14, 2022 – February 12, 2023

Although our eyes have become accustomed today to seeing an infinite range of colours on all kinds of objects, from advertising hoardings to cartoons, prints and photographs, it has not always been this way. In ceramics, as in the cinema, colour was the goal of a long and sometimes painstaking quest, as well as being the cause of unprecedented rivalry.

This exhibition tells the often turbulent story of the quest for colour on porcelain in China and France. It contrasts two crucial moments in the history of porcelain driven by the desire to extend the range of enamels. They occurred at the turn of the 18th century in China and during the 19th century in France, two periods during which the interactions between Europe and China, whether cultural or belligerent, were particularly intense.

The first room in the exhibition introduces visitors to enamelling techniques, the notions of translucent and opaque enamels, and to the famille verte and famille rose. This is followed by a presentation of Chinese enamelled porcelain, principally from the reigns of Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-35), and Qianlong (1736-95), which are among the jewels of Alfred Baur’s collection and which exemplify the use of colour on porcelain over a period of more than a century. The new palette developed in the imperial workshops was soon exported from the port of Canton on porcelain and copper-enamel wares on that had been specially designed for the Western market.

The second section of the exhibition takes place a century later in France, at the Sèvres manufactory, where Chinese colours, long coveted for their brilliance, were keenly researched. Missionaries, chemists, and French consuls in China all contributed to bringing back samples to France where the mysteries of Chinese manufacturing techniques could be fathomed.

The last part of the exhibition introduces more contemporary research on the use of colour, first of all by Fance Franck (1927-2008), who from the late 1960s worked with the Sèvres factory to recreate the famous “fresh red” or “sacrificial red” that had been mastered by the potters in Jingdezhen several centuries earlier. The exhibition’s investigation into this endless chromatic quest is brought to a close by the pure and gleamingly colourful works of Thomas Bohle (born in 1958).

Exhibition Curator: Pauline d’Abrigeon

Scenography: Nicole Gérard

with the assistance of César Preda and Corinne Racaud

Administration and coordination: Audrey Jouany Deroire

Communication: Leyla Caragnano

With the exceptional participation of the following institutions: Musées d’Art et d’Histoire de Genève, Musée Tatiana Zoubov, Sèvres – Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Musée Ariana.

A new palette

At the turn of the 18th century, a real chromatic revolution took place in the field of painted enamel in China: the range of colours expanded from a fewer than a dozen to an infinite number of shades.

Enamel consists principally of crushed glass and a fluxing agent, such as lead, to lower the melting temperature to which a metal-oxide colourant may be added. This is applied to the surface of ceramics during a second, low-temperature firing in small “muffle” kilns. In China, the first painted enamels were created in the kilns in Cizhou during the 13th century. Until the 18th century, these enamels were composed of flat translucent tints that permitted almost no alterations of shades, not to mention blends of different tones. Wucai 五彩 (lit. “five colours”) and doucai 鬥彩 (“joined colours”) developed during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), allowed the existing underglaze cobalt blue to be combined with these few overglaze enamels: red, aubergine, yellow, black, and pale and dark green. In the course of the first half of the Kangxi era (1662- 1722) under the Qing (1644-1911), blue was applied over the glaze and green was used increasingly in the painted decoration. At the end of the Kangxi period, new coloured enamels appeared, in particular an opaque white that allowed mixing of colours to create different shades, as well as a pink enamel obtained from colloidal gold, a formula known in Europe as “purple of Cassius”.

In the 1860s, based on the study of exported Chinese porcelain, two French authors, Albert Jaquemart (1808-1875) and Edmond Le Blant (1818-1897), coined the terms famille verte and famille rose. The first refers to the predominantly green porcelain wares of the first half of the Kangxi era, the second to the carmine porcelain produced from the start of the 18th century. Use of the word “famille” (family) may come as a surprise: it is borrowed from botany, a science that had gained widespread acceptance at the time in terms of classification. The two terms are still used to this day in Western languages, while other terms are used in Chinese depending on the context: hua falang 畫琺瑯 (lit. “painted enamel”), yangcai 洋彩 (lit. “foreign colours”), fencai 粉彩 (lit. “powdered colours”) or falangcai 琺瑯彩 (lit. “coloured enamels”).

The Jesuits at the Chinese imperial court and the development of new colours

The revolution in decorative colours in the production of Chinese porcelain at the turn of the 18th century was closely linked to the presence of Jesuits at the imperial court. In 1685, a group of six French Jesuits led by Jean de Fontaney (1643-1710) was sent to China by Louis XIV to establish a mission. On his arrival, Jean de Fontaney wrote from the port of Ningbo to ask for European enamelled objects to be sent to him as gifts for the emperor. These painted enamels, some of which are still held in the Chinese imperial collections, were diplomatic gifts of the highest order. Chinese fascination

with these European objects, and their painted decoration not unlike an oil painting, may have been pivotal in the emperor’s decision to set up imperial enamelling workshops in the Forbidden City in 1693.

Three years later, the German missionary Kilian Stumpf (1655-1720) established a glassmaking workshop near the Jesuit church in Beijing. The imperial workshops developed into centres of profuse artistic activity that brought together craftsmen and artists with different specialities and fostered experimentation into new techniques and materials. In this context, new colours – such as white, rose, Naples yellow, lime green – made their appearance on porcelain in China.

The development of new colours was partnered by profound changes in manufacturing techniques: the use of kilns dedicated to the firing of enamels, and the use of oil instead of water, glue or soluble gum to dilute the enamels allowed the painting of finer lines, creating effects similar to painting on canvas.

From the 1690s onwards, the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662-1722) requested that a European enamel painter be sent to the court. In a letter dated 1716, the Jesuit Matteo Ripa (1682-1746) relates how he and his Jesuit colleague Giuseppe Castiglione (1688- 1766) were insistently requested to paint on enamel. Unhappy to consent to such forced labour, they two Jesuits painted so badly that the emperor gave in and declared “Enough!” That same year, Kangxi also received craftsmen from Canton at court, where enamelling workshops had been set up at the start of the 18th century. It was not until 1719 that the Jesuit enameller Jean-Baptiste Gravereau (1690-1762) finally arrived in China, at a time when many European techniques had already been assimilated or adapted.

Exporting the new palette

The new colours developed in the imperial workshops were soon imitated in private commercial kilns, whose products were in part made for export. With their gleaming decorative designs, these new porcelain wares met with great success in Europe. In the 18th century, Canton was the only Chinese port to trade with the outside world. An area overlooking the port, on the edge of the Chinese city in the heart of Canton, was reserved for foreigners. It was here that the East India companies, in particular the English and Dutch, purchased supplies of tea, silk, lacquer, wallpaper as well as porcelain. Although most of the pieces they imported until the 17th century were blue-and-white, the turn of the 18th century saw the appearance of polychrome porcelain on the market. As with all innovation, polychrome pieces were sold at a higher price. They were designed to provide a range of services to cater for the growing consumption of tea and coffee, and were sometimes decorated with their owner’s coat of arms. Polychromy, and the prevalence of pink and gold, were particularly suited to the fashionable Rococo style in Europe.

Towards the start of the 18th century, enamelling workshops were established in Canton to better meet the specific decorative requirements of Westerners: the pieces, which were still produced in the porcelain capital Jingdezhen, arrived undecorated in Canton where they were painted with differently coloured enamels.

Enamelling was not limited to porcelain, but also applied on metal. Enamels painted on a copper alloy became a speciality of Canton, to the extent that the term “Canton enamels” is used to describe this form of production. Copper enamels were made for export – as the forms of some of the pieces in this section of the exhibition bear out – but also for the imperial court. The nature of the decoration and the presence of reign marks (nianhao 年號) on the underside of the pieces indicate this particular destination.

Chinese documentation attests to the frequent exchanges between the imperial court and officials in Canton: the circulation of objects, craftsmen, and new materials freshly arrived from Europe contributed greatly to the development of a new palette of enamel colours in China.

Research into Chinese colours at Sèvres manufactory

Another time, another place. The following room will introduce you to the manufactory at Sèvres close on a century after the experiments on coloured enamels were carried out in China.

Beginning in the 1830s, Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), the learned administrator at the Manufacture de Sèvres, attempted to get hold of materials and information on Chinese production techniques by asking for the help of merchants and consuls of all nationalities who had the opportunity to visit China. His endeavours remained fruitless until he came into contact with the congregation of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, whose Lazarist missionaries were established in China. Father Joseph Ly (Li Yuese 李約瑟, 1803-1854) was finally commissioned to collect materials in China from where he brought back clays, porcelain pastes and various enamel colours.

In 1844, Jules Itier (1802-1877), a member of a trade delegation and a talented daguerreotypist, also brought back a series of colours he had purchased in a Canton enamel workshop: having succeeded in getting into “the workshops of Canton’s largest manufacturer” in the district then called Henan 河南, he bribed a craftsman painting ceramic pieces with a few piastres to allow him to take away brushes, colour pots and other equipment used in enamel painting. Just a few years later, the British consul in Shanghai, Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897), also sent off a considerable number of pigments to the Sèvres manufactory.

These various shipments were analysed by the manufactory’s chief chemist, Alphonse Salvétat (1820-1882), on their arrival at Sèvres. Starting in 1848, he carried out tests to imitate the Chinese copper red – known in the West as “oxblood” – a colour that was particularly difficult to obtain. He also understood that the translucent Chinese enamels, admired for their bright, gleaming colours, could only be imitated by altering the composition of Sèvres’ porcelain paste.

In 1875, the French chemist Anatole Billequin (1836-1894), a teacher at Tungwen College in Beijing, was commissioned to bring back Chinese ceramics to the Sèvres manufactory. These were studied to learn more about the Chinese nomenclature given to the colours applied to ceramics: “aubergine violet”, “leek green”, “eel-skin yellow”, or the “mule’s liver, or horse’s lung”.

Sèvres was not the only porcelain producer to have an interest in Chinese colours. In the second half of the 19th century, the ceramists Théodore Deck (1823-1891) and Ernest Chaplet (1835-1909) succeeded in producing pieces with flambé, celadon or turquoise-blue glazes on porcelain or earthenware, fully the equals of their Chinese models.

Fance Franck

This last room introduces more contemporary research into colour, exemplified by the work of ceramist artist Fance Franck (1927-2008). Born in Montgomery (AL) in the United States, she spent the greatest part of her career in France where, with the artist Francine Del Pierre (1917-1968), she founded a workshop in Rue Bonaparte, Paris.

In 1969 she began a series of experiments to rediscover the ancient Chinese method used to create “fresh red” xianhong 鮮紅 and “sacrificial red” jihong 霽紅 using copper oxide as a starting point. Like the potters of Jingdezhen several centuries earlier, she had to deal with the colourant’s extreme versatility, which is only revealed by perfectly controlled high-temperature reduction firing. Very often, even if applied in the same way and in equal proportions to two pieces of the same shape and fired in a similar way, the colourant produces completely different coloured effects.

In 1971 and 1972, Fance Frank conducted tests over a period of months. Antoine d’Albis, the head chemist at Sèvres manufactory, provided her with a porcelain paste of his own composition for her experiments, and in spring 1972 she succeeded in producing pieces which she considered satisfactory. She then went to the Percival David Foundation in London where, with the encouragement of John Pope and Margaret Medley, she compared her experiments with the copper reds of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

In addition to the technical aspect, Fance Franck immersed herself in the symbolism of the colour, its significance in Chinese linguistics and mythology, and of course its place in the history of Chinese ceramics.

Her research led Fance Franck to visit numerous collections, including the Baur Foundation’s, where the then curator Frank Dunand (1937-2014) showed her a “fascinating stem cup” dating from the second half of the 14th century, during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). The Foundation was therefore particularly keen to reconnect with her story by presenting some of the artist’s finished pieces, as well as a large number of test pieces from the workshop’s collection illustrative of her intense research.

Thomas Bohle

Thomas Bohle, the artist invited to exhibit at the Baur Foundation in the context of its partnership with the 50th Congress of the International Academy of Ceramics and the Parcours Céramique Carougeois, brings the exhibition’s chromatic investigations to a close.

Born in 1958 in Dornbirn, Austria, Thomas Bohle was 26 the first time he sat at a potter’s wheel. Influenced in particular by the ceramics of the Song period (960-1279), he directs his attention towards the creation of pure forms and shimmering glazes.

To arrive at a piece’s colour, Bohle starts from its form. It is often while shaping the piece that the first ideas for the glaze come to him. The colour, as if melted into a thick layer of glass, contrasts with either a matt black glaze or the fired clay left bare. Thus, the interior and exterior of these silhouettes, which always suggest a container without ever evoking a precise functionality, are characterised by the dissimilarities of these materials. However, container and content meet in a single wall of clay that encloses and protects a space of emptiness. Most of the pieces presented here are the fruit of this virtuoso technique, in which the outer wall and bottom of each work are produced as a single piece in a play of curves and counter-curves.

The colour on the rims of certain pieces seems to be almost organic, where it flows, motionless, in droplets frozen in time and space. These alone embody the fragile versatility of the material on its technically perfect support. Thomas Bohle’s palette ranges from midnight blue to a luminous matt yellow; here a black ground shining like lacquer, on which touches of emerald-green amplify the brilliance; there, bluish celadons evoke the shimmer of crystalline water.

Oxblood glazes have a special place in Thomas Bohle’s work: the unpredictability of this colour provides the artist with a lesson in humility, and sometimes invites him to renounce his expectations and simply accept the often very singular beauty of the pieces as they come out of the kiln.

His works are also present in the permanent collection, like touches of colour in dialogue with the Chinese ceramics of bygone centuries.

Contact

musee@fondationbaur.ch

Baur Foundation, Museum of Far Eastern Art

Rue Munier-Romilly 8

1206 Geneva

Switzerland

Photo captions

- Famille verte dish with phoenix, Porcelain and translucent overglaze enamels, d. 52 cm. China, Qing dynasty, mark and Kangxi period. © Fondation Baur, musée des arts d’Extrême-Orient, Genève, photo Marian Gérard

- Bowl with floral and leaf decoration, Porcelain and overglaze polychrome enamels, d. 12,5 cm. China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi mark and period. © Fondation Baur, musée des arts d’Extrême-Orient, Genève, photo Marian Gérard

- Fance Franck (1927-2008), Two cups on high foot, Manufacture de Sèvres porcelain, Decoration and red copper background, left: h. 22.7 cm, 1973; right: h. 22.9 cm, 1978. © Atelier Fance Franck, collection Jean d’Albis, photo Nicolas Foucher

- Thomas Bohle, Vessel, Double-walled stoneware, cobalt-green enamel, h. 17,5 cm, Reduction fired at 1280 °C. Collection of the artist © photo Frigesch Lampelmayer