Yasuhara Kimei, Ikebana Sogetsu, and the Art of Japanese Ceramics

Dai Ichi Arts is delighted to present “Object, Vessel: Yasuhara Kimei, Ikebana Sogetsu, & the Art of Japanese ceramics”. This exhibition celebrates the profound ceramic works of Japanese potter Yasuhara Kimei and his subsequent impact on both the influential Sodeisha movement, and the Ikebana Sogetsu school in Tokyo. This show is the first exhibition in the West to present a collection of Yasuhara Kimei’s works, showing the gallery’s longstanding commitment to presenting the heart of Modern and Contemporary Japanese ceramics.

Little known in the West, Yasuhara Kimei (1906-1980) was one of Japan’s most avant-garde ceramic artists of the 20th century. Best known for his “Sekki” flower vases, his ceramic work inspired the innovative floral artists of the famous Ikebana Sogetsu school and produced a transcendental impact on modern potters and Ikebana artists alike in Japan that has lasted generations. In particular, his conceptualization of the “Object Vase” inspired the founders of the important Sodeisha school, Yagi Kazuo & Kumakura Junkichi.

Yasuhara Kimei’s Significance in the World of Ceramic Art

Abridged essay by Kazuko Todate, published on the occasion of “Object, Vessel: Yasuhara Kimei, Ikebana Sogetsu, and the Art of Japanese Ceramics” at Dai Ichi Arts

Yasuhara Yoshiaki (known in the west as Kimei), was born in Tokyo in 1906. His father was a sailor on a foreign route. In 1924, at his father’s urging, he studied pottery making techniques under Miyagawa Kozan II (1842-1916) in Yokohama, and around 1927, he studied under Itaya Hazan (1872 – 1963), learning how to be an individual ceramic artist.

It is important to note that Yasuhara learned from both a master craftsman and a pioneer ceramic art at the start of his pottery career. Miyagawa Kozan II inherited the Makazu kiln, which had been in operation since the Meiji period (1868-1912), and was the master of a large pottery workshop with over 100 craftsmen, and was well versed in various ceramic techniques. On the other hand, Itaya Hazan, like Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886– 1963) and Kusube Yaichi (1897–1984), was a pioneer of individual ceramic artists in the 20th century, who studied “creativity” at art school and established himself as an artist by exhibiting his works at exhibitions.

This means that Yasuhara was able to learn from the most talented ceramic artists of his time the necessary requirements for a ceramic artist: a broad range of traditional ceramic techniques and authorship (creativity). Yasuhara’s later work in an extremely wide range of techniques, including pottery, porcelain, and stoneware (especially glazed, non-glazed, inlaid, and painted porcelain), and the development of his own expression using these techniques, were based on the knowledge and teachings he had learned from Kozan and Hazan from the beginning of his pottery making career.

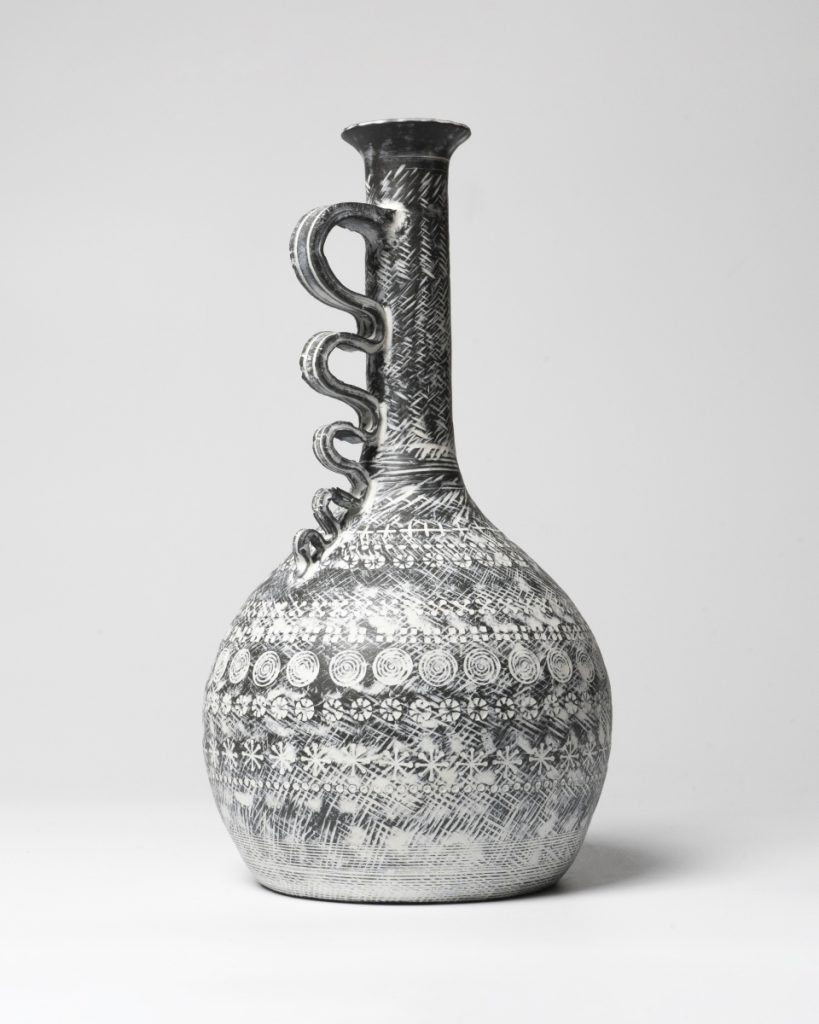

One of Yasuhara’s best-known series is what he called “Sekki 炻器 (Stoneware)”. Molded in grayish-blue clay mixed with pigments, the surface is carved with a unique pattern, then filled in that carved line with white clay and fired at high temperatures. The vessels look modern and solid, but at the same time, they have a dignified and stately atmosphere, as if they were excavated from some archaeological site. Yasuhara’s vases are sometimes reminiscent of “ships” or “harbors” in shape. This may be due to the fact that his father was a sailor.

In the mid-1930s, Yasuhara had another important encounter, following Kozan and Hazan. This person was Teshigawara Sofu (1900-1979), the founder of the Sogetsu school of ikebana. Teshigawara probably came to know Yasuhara at his first solo exhibition at Shiseido gallery in 1934.

Tea masters and flower arrangement artists are the natural companions for ceramic artists in the course of their work. In the early modern period, tea masters mainly instructed the potters, and masterpieces of tea ceramics were produced. Ceramic artists are still involved in tea ceremony ceramics, devising “expressions” in the limited sizes of tea bowls and water jars.

On the other hand, flower vases are also a typical item for which ceramic artists receive orders. In the mid-twentieth century, the world of ikebana has provided ceramic artists with even greater formative inspiration than the tea ceremony. For example, the creative provocations of the flower arrangement artists, who were inspired by the avant-garde trends of Western art, were also behind the postwar efforts of the Shiko-kai artists to create ceramic objects. Among the several schools in Japan, Misho, Ohara, and Sogetsu are said to be the three major schools. Kansai ceramic artists including Kyoto such as Hayashi Yasuo are more closely associated with the Misho school, while Kanto artists including Tokyo such as Yasuhara tend to associate more with the Sogetsu school of flower arrangers.

Around 1937, Yasuhara began creating vases for Teshigawara Sofu. At that time, Teshigawara was exploring ikebana art as a creative new form and space, rather than formalized ikebana. Radical ikebana artists like Teshigahara were quick to learn about the objects of the Surrealists and Dadaists in Western art from magazines of the time, and began using terms such as “obuje (objet d’art)” and “obuje kaki オブジェ花器 (vase as art object)“. Ceramic artists who had been in contact with flower arrangement artists also began to produce vases with a different formative and creative style. Yasuhara, who had been in contact with Teshigawara, also began to expand his expression considerably from the late 1930s onward.

Although each of these works by Yasuhara is a functional “flower vase,” as the title suggests, the overall impression is that of an object. Yasuhara’s tube-shaped composition series may have influenced Yagi Kazuo (1918 – 1979)’s first objects.

Perhaps Yasuhara was always consciously trying to make room for “flowers” in his own functional ceramic works. This is the underlying attitude of Yasuhara, who was a close friend of Teshigawara Sofu and the Ikebana Sogetsu School. Yasuhara’s attitude of pursuing new ceramic forms may have been synchronized with Teshigawara’s attitude of seeking new expression in the world of flower arrangement, and Yasuhara may have sought to further expand his own formative expression through collaboration with flowers. In other words, Yasuhara’s ceramics seem to regard the “vase” itself as an important part of the “flower arrangement object”. Moreover, Yasuhara’s flower vases have a certain autonomous presence as individual forms, even without flowers.

One of Yasuhara Yoshiaki’s most important formative qualities and achievements, is his ultimate establishment of the noble and modern robust “object vase,” designed to become a new object when flowers are inserted, pushing the limits of the binary categories of functional and sculptural in the world of Japanese ceramics.

Contact

info@daiichiarts.com

Dai Ichi Arts Ltd.

18 East 64th Street, Suite 1F

New York, NY 10065

United States

Captions

- YASUHARA Kimei 安原喜明(1906-1980), Flower Vase 炻器花生, Ceramic with Matte Black Glaze and Incised Motifs, H10.6″ x W5.7″, H26.9 x W14.6 cm

- YASUHARA Kimei 安原喜明 (1906-1980), Flower Tall Vase 花生線彫文炻器, Ceramic with Matte Black Glaze and Incised Motifs, H11.7″ x Diameter 6.3″

- YASUHARA Kimei 安原喜明 (1906-1980), Flower Vase 花挿, Ceramic with Matte Black Glaze and Incised Motifs, H12″ x Diameter 4″

- MIYANOHARA Ken 宮之原 謙 (1898-1977), Tenmoku Glazed Large Jar with Handle 朱天目釉手付壺, Stoneware, H13.7″x Diameter 9.5″

- KUSUBE Yaichi 楠部彌弌 (1897-1984), Turquoise Blue Glaze Flower Vase with Flower Bud Shape 蒼釉萌花瓶, Stoneware, H9.4″ x Diameter 5.8″

- Kumakura Junkichi 熊倉順吉 (1920-1985), Glazed Rectangle Jar 釉彩角壷, Late 1940’s, Stoneware, H6″ x W4.8″ x D2″