You find something particularly human in porcelain: “it can suggest the weight of corporality as effective as it captures the translucence of spiritual experience”. When and how did you discover its capabilities?

Early in graduate school when I began experimenting with sculptural work, I was initially drawn to porcelain for its smooth elasticity that I hadn’t experienced in the stoneware and red clays I had been using. It moved nicely in my hands. My first sculptures were very heavy, weighted items. I had very little formal clay training, so it was all trial and error.

I began to study porcelain artists who pushed the opposite end of porcelain’s capabilities. They inspired me with very their thin and translucent work. At the time, I was immersed in the writings of James Hillman about the soul of the artist and Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Both explored ideas about contradictions of life, how our bodies can be heavy with burden, yet light with the insignificance of being one transitory soul in this great system. I began looking at the contrast between the fragile, translucent porcelain and the heavier weighted pieces I had been creating. I started to explore methods to get my clay to remain structurally intact while thin enough to let the light through. Porcelain slip allowed me to push this even further. I was fascinated by its ability to be both heavy and light, similar to the spiritual experience we have in life.

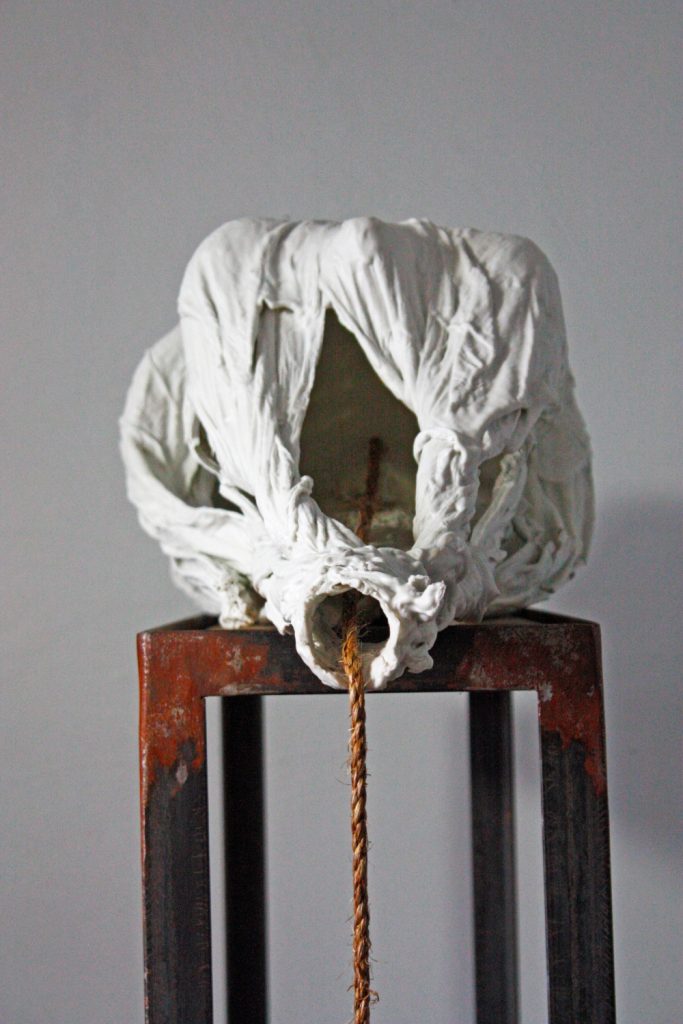

It all came together for me, however, as I began experimenting with firing. I learned from some very experienced colleagues that the porcelain clay body has this point in the kiln where it will begin to slump. If you manipulate how you place something in the kiln – by setting it up on stilts in precarious situations – you can take advantage of this property, and the porcelain seems to sag or stretch at just the right moment when the kiln reaches its highest temperature. As it cools, this movement is locked in place, and the gesture that I wanted to convey is amplified since it moved beyond where the clay could go prior to firing. This movement is very human, as though the material had a mobility of its own. This corporeality along with the spiritual connection between the heavy and light porcelain transformed the way I saw my work. This is why in my work the porcelain pieces are the body. They are the human element.

“I have always felt hyper aware of my emotions and what I perceived to be other people’s emotions.”

What emotional states do you express through visual representations of precariousness, fragility, and tension?

I like to watch people, and their physical reactions to situations they aren’t even involved in. If a group of ballet dancers enter the room, everyone seems to sit a little taller, straighten out their backs, a subconscious reaction to feeling a little insecure in comparison to the perfected postures ballerinas have. If a stack of books sits wobbling on the edge of a table, a viewer will sit on the edge of their seat. They will jump with a start when the books hit the floor, as though they, themselves, were stressed by the pending fall. Our bodies manifest outwardly what we are feeling on the inside. Precarious situations make us nervous, edgy, and uncomfortable. Seeing something fragile may make us feel protective and cautious; or may leave us feeling free, unburdened and buoyant. When we experience tension in a personal relationship, we feel conflicted, tight, heavy with worry.

I think making art, and perhaps being a creative person, in general, can be very manic. Your emotions can waver between complete inspiration and ingenuity to a forlorn sense of being directionless. I have always felt hyper aware of my emotions and what I perceived to be other people’s emotions. You can see in their physical demeanor that something is influencing them, but I think people are often unaware of it. We brush these feelings aside to carry on with our day. Putting my sculptures in these physical states is my way of giving significance to these daily emotions and the way we feel them in our bodies. It gives an object that we can pause over and reflect on.

Do you believe the viewers can experience the same tension and physical stress that you do?

This is my intent. But I think that it can differ based on what is going on with your life and your experiences. Many pieces mean different things to me at different times. Often, I am just making, and I don’t quite know where it is coming from. Months or years down the road I can look at it and know that a big life change or emotional moment was occurring at the time of creation, and I’m almost embarrassed at how literal it seems to me. I enjoy hearing from people what my pieces bring up for them. Sometimes if someone I know quite well is drawn to a specific piece, I feel quite sure that I know exactly why, based on their personality or what is going on in their lives.

Through the firing process, you preserve and even amplify the human gesture your sculptures take on during their creation. How do you create a new piece? What techniques do you use?

I rarely have an idea of what a piece will be in its final state when I begin working on it. Sometimes it starts with a technique I want to use, or I just flow with what I am feeling. My three primary ways of working right now are through slip dipping fabrics and sculpting with them, hand building, or manipulation of slip cast pieces. When I slip dip fabric, I have to be in my creative flow to have any success. It’s a pretty subconscious way of working. I have thoughts, feelings, sketches, inspiration of what is emotionally moving me at that moment, and I just create. When the fabric is thick with porcelain slip, it takes on a very skin-like, leathery feel. It’s amazing to work with, although very hard. It is also very time-limited. Once the fabric-dipped piece begins to get tacky, you are done, the ability to work the material stops. You can add bits on or make small manipulations, but the big gestures have been set. This limitation inspires me. It reminds me to leave perfection out of it and go where it takes me.

I long ago let go the notion of waste. Many things I create in my studio never see the light of day and my way of working and firing produces much trial and error. However, even a failed attempt can lead to an idea that turns into a great studio success. After I have created many of these pieces, I do a big firing. The fabric pieces are actually at their most durable state when they are bone dry but are far too fragile when bisque fired to be moved, so I just fire everything once. When they come out, there is a period of contemplation in the studio where I try to discover what the porcelain parts – the body – need to be completed. Do I need multiples? Could I add additional parts to put it into a situation that tells me a story or expresses a physical or emotional state? Does it need to be re-fired on stilts in an attempt to manipulate its shape or gesture? This is where a lot of my found objects such as steel, wire and wood play a role. I use these to create an environment for the porcelain piece. My studio is always full of my porcelain pieces. Sometimes they sit dormant for years before they find their home in a finished piece.

There is a contradiction in your work between the precious porcelain and the metal or found objects that you use. What does this contrast reveal?

It started as just an aesthetic that I was drawn to because of my architectural background and the fact that I live in the rust belt, where cities are full of the beautiful detritus of their past mixed in with the new. I love that look, and I love that feel of the clean and dirty co-existing. It didn’t take me long to discover that this contrast between the old, rusty, deteriorating elements with the precious, clean and often fragile porcelain provokes the tension that I am often trying to convey. The metal pieces particularly can be oppressive, yet the stark and intriguing porcelain is what draws you closer; it lifts right out of the sculpture. Manipulating the relationship between these parts allows me to decide what the feel of the piece is going to be. Who is dominating, the light, the beautiful? Or will the precious be suppressed, held back, held down by the environment around it?

Before completing your MFA in ceramics, you studied architecture and worked in that field for several years. When did you know what you have a passion for ceramics? What prompted the change?

I highly value my architectural education. The program had a strong art development component. We drew by hand, water colored, visited many museums and studied a year in Italy where I experienced art like I never had before. Upon returning from my year in Rome, I wanted more of that freeing kind of creativity that I was surrounded by there. Architecture is so specific; I decided on a whim to take an elective ceramics course and immediately fell in love with working in clay. I continued to do ceramics as independent studies when I had taken all the formal classes.

After school, I worked four years in urban design and architecture. Although I loved many aspects of it, I didn’t find the practice of architecture as creative as its formal education and I began to feel a bit lost and unfulfilled. I think it was the lack of creating things with my own hands that I was missing. During a job change, I took a couple months where I worked only part time, and I spent the rest of my time at the Union Project ceramics co-op that made me incredibly fulfilled and happy. So I decided to take the leap and pursue my MFA. Mostly, I wanted a period where I could concentrate directly on my art and create a body of work. I had no idea how influential school would be in completely transforming my creative thought process and change the direction of my development as an artist. I am a pretty practical person, so it was a big risk for me to get a degree in a field that I knew was financially insecure, but I figured that the pay-off in my happiness and spiritual growth would be worth it. It certainly has been.

Did you have a mentor when you were growing up? How about in your development as an artist?

I’ve had so many people who have supported me along the way. Growing up my maternal grandmother, Dottie was a big influence on me. She was a very creative person and a pure lover of life. She designed and sewed her own clothes and taught us that if you could make things with your own hands, you would never be bored. My parents always did a god job of creating opportunities to pursue creative endeavors for my brother, sister and me. They found art classes and programs for us to be involved in outside of school, and I tried just about every type of art, dance, or theater class that was out there. I think that creativity can easily get stifled in youth, and I am so glad that was not the case in our family.

In graduate school at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, I had some fantastic professors, Linda Cordell, and Sumi Maeshima, who pushed me to venture into working sculpturally. They had to work hard at this. I was insistent on continuing to make only functional ceramics. When they finally broke through to me, I found I really enjoyed the freedom of letting go of the need for art to function as anything aside from art. However, the biggest influence on my development as an artist has been my mentor Ed Eberle, an exceptionally talented porcelain artist whose studio is in Homestead, near Pittsburgh. He opened me up to new ways of thinking and introduced me to some reading that evolved my creative process. He also broke down the self-consciousness that was holding me back. He convinced me that just making things, and being true to myself in what I was making was the art, forget about everything and everyone else. Having this support and encouragement from someone I deeply respected and admired as an artist helped me to let go of the doubt that was holding me back. He openly shared his wealth of knowledge on technique, process, and technical skill. Ed continues to mentor me, long after my formal schooling has ended. For this, I am tremendously grateful.

2015. Interview by Vasi Hirdo, published in Ceramics Now Magazine Issue 3.

Visit Erica Nickol’s website.

The interview is copyright of Ceramics Now and Erica Nickol, and cannot be reproduced without permission. All images are copyright of the artist unless otherwise stated.