In the brick vase clay cup jug exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Glenn Barkley presents a novel approach to curation. Drawing on the gallery’s online collection database, his selection of artworks is a poetic convergence of randomness and intuition. The resulting exhibition offers a fresh perspective on the connections between seemingly disparate objects. Alongside this, Barkley’s recent release, “Ceramics: An Atlas of Forms,” takes us on a global journey through the history of ceramics, sharing the stories of over 100 clay objects. This interview offers a glimpse into Glenn Barkley’s creative process and explores how blending art, history, and form can tell stories that span time and cultures.

Can you walk us through the inspiration behind using the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ online database as the primary tool for curating the show?

I was approached to curate an exhibition for the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney with a relatively short lead time, which led me to think of something that may have been more intuitive rather than over-intellectualised. I have worked as a curator for more than 20 years, and I have always appreciated the way that gallery storage has its own particular logic. I wanted this logic in some way to guide the ‘who’ but also to create an arbitrary way of creating content. There were, of course, some linkages I wanted to make and that I knew, but I also wanted to see what unexpected links could be made by just using almost arbitrary terms around which to shape the selection.

Were there any surprising or unexpected connections between artworks that emerged through this non-hierarchical approach to selection?

Whenever you bring a group of things together, a conversation starts to take place. This could be about the way things are shaped – from the simple similarity of rims and apertures – to the way marks are made and how that might carry from a three-dimensional surface to two-dimensional. Textures and materials also tether objects together.

I think the great strength of ceramics is its material memory – it holds history and fixes it in a way other art forms may not. There is, for instance, a series of narratives that run through the show that are entirely unintentional, such as the role ceramics have played in trade; or even the preponderance of a particular glaze, like tenmoku, and how that bounces around from the ancient past to the present. Other themes reveal the more prosaic life of ceramics as a building block, like a brick or as raw material extracted from the earth.

I think the best art of curating is bringing artworks together and see what chatter it might create when installed – chatter that may be enabled or enhanced by the space and installation.

Traditional curation often leans on historical context or artistic movements. How did it feel to move away from these conventions and to trust visual and intuitive connections?

I’ve always tried to be intuitive beyond anything else as a curator, but as both a curator and a maker, I feel my way of looking has changed and is done at the tips of my fingers. The great privilege of curating this show was being afforded the opportunity to spend time with objects in a personal way – holding, lifting, turning – and being assisted in this by the amazing curators at the Art Gallery of NSW who have deep and inspiring knowledge of these objects.

The exhibition also includes a new iteration of The Wonder Room. How did the collaboration with the communities of the Shoalhaven come about for this project, and what significance does it hold within the context of the exhibition?

The Wonder Room was created with a group of maker-collaborators based in the Shoalhaven region south of Sydney, which is the place where I grew up. The workshop was facilitated by the team at the Shoalhaven Regional Gallery in Nowra.

The work takes the form of a ‘house’ clad in over 700 terracotta tiles, each tile decorated by a person from the region responding to the idea of what makes the Shoalhaven special to them. Most of the participants are not artists or ceramicists and their responses are moving, funny and direct.

The Shoalhaven region has a long Indigenous history and the First Nations people there were some of the first to encounter the colonisers. I’m proud to say that many of the tiles in the Wonder Room were created by many First Nations groups from older to younger.

This work is one of the first instances where the Art Gallery has brought a work in from a regional gallery, as their touring programs usually takes their exhibitions to the regions. That fact alone makes it significant, but the human responses illustrated on the tiles and the sheer number of the participants have led many people for the first time visiting the galleries in Nowra and Sydney and emphasising these galleries civic and cultural roles within their communities.

How did you envision visitors navigating and experiencing the exhibition, and how did that compare to the reality once the show opened?

I always knew the exhibition, brick vase clay cup jug, would involve more work than a typical Art Gallery hang, but I think audiences always respond well to content. I think the public like seeing things. And why not? If it had been up to me, it would have been denser!

We have been quite light on text as we want people to impose their own logic to the hang. For instance, there are no labels. Rather, things are numbered in a catalogue that is accessible in brochures or through your phone. This is a daring thing for a gallery to do and I know it hasn’t been universally liked.

Do you see this method of curation – based more on serendipity and intuition rather than a fixed theme or concept – influencing future projects?

I can only speak personally, but it is a way I like to work. I appreciate the Art Gallery allowing me to work in this way. I think my role has shifted from first being just curator to now being an artist curator – an important distinction. When you add the word artist all of a sudden other possibilities open up and you can start to bend and break some orthodoxies – from display methodologies to the use of didactics.

In saying that, I also understand that some curators want to do that, but often, the expectations and responsibilities of their roles and the balancing act of public, artist, donors, and art history can weigh you down and tighten you up.

You recently released a new book, Ceramics: An Atlas of Forms, a global cultural study of the history of ceramics, sharing the stories of over 100 objects. With ceramics having such a vast history, how did you decide on the specific objects to include in the book?

My book, Ceramics: An Atlas of Forms, runs parallel to the brick vase clay cup jug exhibition and is another kind of overlay. The book explores the global history of ceramics from the perspective of Australia looking outwards, whereas most global histories tell a European pr or English-centric history shaped by colonial prejudice. For instance, my book includes artists from Australia, the Pacific and First Nations artists from Australia and elsewhere who have been mostly absent from other global histories.

It uses, not exclusively, collections from Australia and New Zealand to tell a global history and often the emphasis is on how that piece ended up here – the ethics of how and why it was collected being an important way to foreground some objects.

Similar to the curatorial approach for the exhibition, I also respond to ceramics as not just a writer but as a maker. There are large format images often showing unexpected details and I respond to things in an emotive and visceral way. I respond to works that are resolutely handmade, where the maker has left an obvious trace, and that are a record of meeting between ideas and material.

Lastly, I have unashamedly brought together a group of artworks that I respond to and that show my personality, and I think it’s important to be upfront about that.

How do you view the evolution of form in ceramics over the ages? Are there distinct patterns or shifts in the language of form that stood out to you during your research?

It’s interesting the way that the hand and eye often return to forms and shapes that to me feel like something the mind knows. Some vessel shapes exist within some deeper recess of the mind that the often feel reassuring. They are part of some deep time muscle memory.

In my own work, which is implicated in any of the work I do as writer and curator, I have an irresistible urge to make something that feels functional. Stranded between function and decoration. I think the strongest and most compelling argument for ceramics is that ambiguity is a useful conceptual and material hook to hang lots of ideas off.

Two things can be true at once, and the work I respond to fits within a band that is both narrow AND expansive that has evolved but still cleaves close to its point of origin. When you start to loosen perceptions such as ‘skill’ or even drawing the raw material of clay into the dialogue around ceramics, the forms endlessly shifting yet always, strangely centred.

How has the advancement of technology, from ancient kilns to modern firing techniques, influenced the forms that artists are making?

I think the advancement of technology is something that is always humming along in any assessment of ceramics across time. How something is made and fired is intrinsically bound up in what it means to the maker and the user.

The current moment, with the rising profile of ceramics in the contemporary art world, is unleashing possibilities in terms of ambitions and scale through the market, injecting capital into the medium. This capital, in turn, drives technology and the infrastructure of and around making. This is further amplified by the other end of the ceramic scale, the amateur maker, whose dalliance may be fleeting but needs ready access to materials and technology that is easy to use and easy to drop in and out of.

The most important thing in terms of contemporary ceramics and technology is that the importance, to some, of a ‘de-skilled’ approach shouldn’t be at the expense of more skilled and more technically driven ways of making and most importantly, teaching. There is such a clear connection between technology and art in ceramics, and it’s important that this is nurtured.

Speaking for myself, I think my technical skills in terms of firing and glazing is rudimentary, but I understand how skilled makers make it easier for someone like me to access technology, use store-bought glazes, and turn on my kiln by just pressing a button.

How do ceramics act as markers of cultural identity, especially when considering their form?

Ceramics have existed for so long and mark all aspects of our lives, from the domestic to the spiritual to the secular. Pots are used to commemorate, to hold, to use, to eat off, to smash. Most human beings have some kind of relationship to the material and ceramics can be culturally specific, deeply personal, and broadly universal. That’s why we people love making with clay, why we can talk about it forever, and why it is so compelling to think about.

brick vase clay cup jug is on view at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until January 2024.

Glenn Barkley is an artist, writer, curator, and gardener based in Sydney and Berry, NSW, Australia. His work operates between these interests, drawing upon ceramics’ deep history, popular songs, the garden, and conversations about art and the internet. He was previously senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (2008–14) and curator of the University of Wollongong Art Collection (1996–2007). Barkley is co-founder of Kilnit Experimental Ceramics Studio Glebe and Co-Director of The Curators Department, an independent curatorial agency based in Sydney. His work is part of the collections of the Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide), the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), Shepparton Art Museum (Shepparton) and Artbank (Sydney).

Interview by Vasi Hirdo, Editor of Ceramics Now, October 2023

Ceramics Now is a reader-supported publication. When you join as a member, you become part of a passionate community dedicated to the growth and appreciation of ceramics. Read more about membership and become part of our story!

Captions

- Installation views of ‘brick vase clay cup jug’, guest curated by Glenn Barkley at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio

- (image 1) Esther Ngala Kennedy ‘Marsupial Mouse Pot’ 1997, handcoiled terracotta, underglazes, glaze, applied decoration, 46.5 x 31 x 31 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1997 © Esther Ngale Kennedy, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

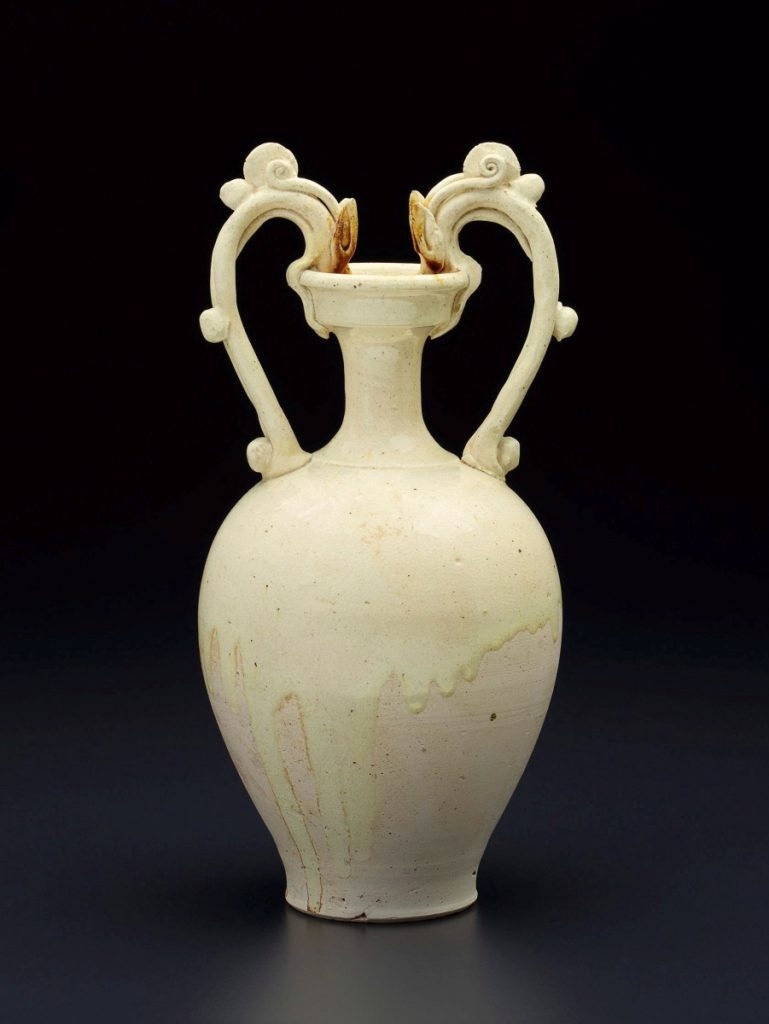

(image 2) China, Tang dynasty 618 – 907 ‘Ewer with double dragon handles’, stoneware partly covered with transparent lead glaze, 30.7 x 14 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1988, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 3) Iatmul people ‘Damarau (sago storage jar)’ mid 20th century, earthenware, modelled, 78 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1965, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 4) Roy de Maistre ‘Still life (pink dahlias)’ c1955, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 55.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, bequest of Mrs Winifred Iris Gay 1994 © Estate of Roy de Maistre, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

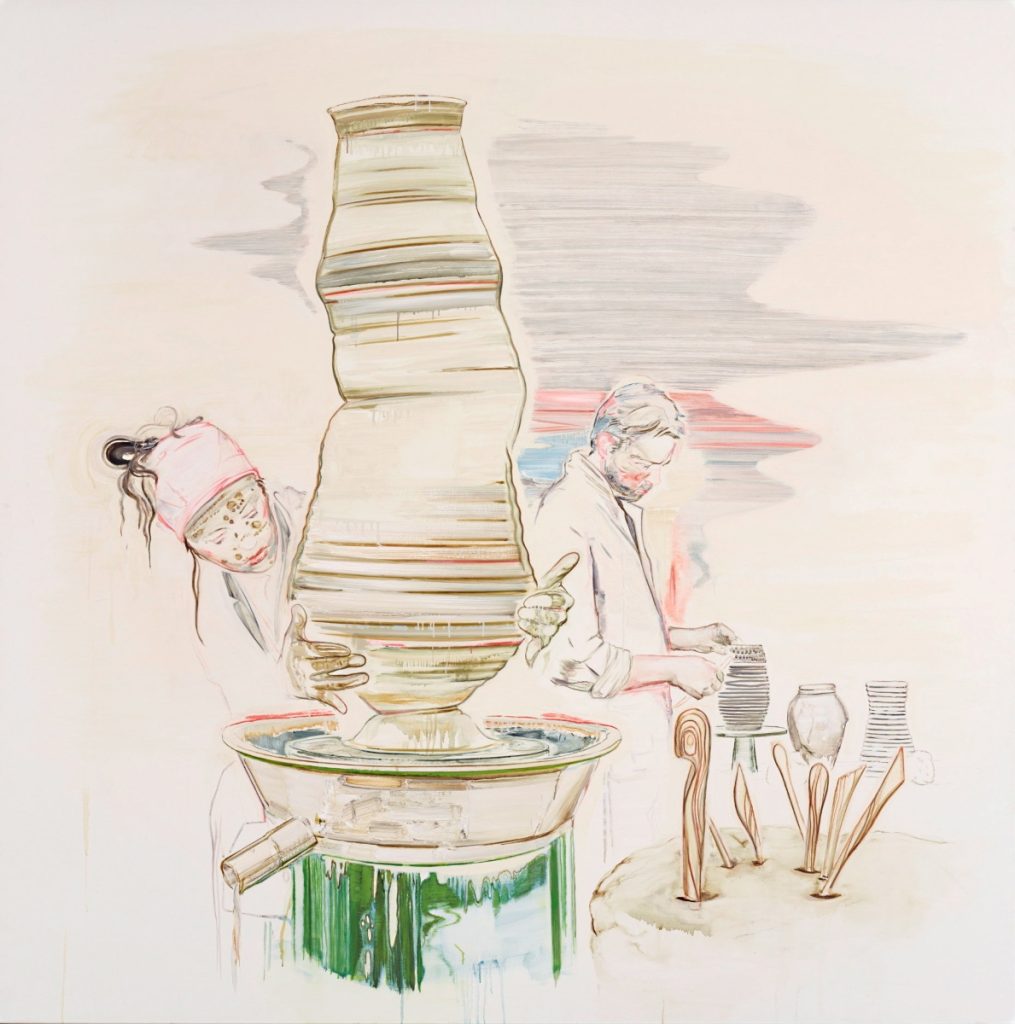

(image 5) Tim McMonagle ‘Plaza’ 2005, oil on linen, 180 x 180 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales gift of Dakota Corporation Pty Ltd 2014, donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program © Tim McMonagle, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 6) Margaret Rose Preston ‘Flowers in jug’ c1929, woodcut, printed in black ink, hand coloured in gouache on thin cream laid Japanese paper, 28 x 20.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1975 © Margaret Rose Preston Estate, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 7) Kirsten Coelho “The crossing’ 2019, porcelain, matt glaze, and iron oxide, 25 x 60 x 25 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Vicki Grima Ceramics Fund 2020 © Kirsten Coelho, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(images 8-9) Dean Cross ‘Untitled (self-portrait as water and clay)’ 2015 (video still), single-channel video, colour, silent, duration: 00:04:43 min; aspect ratio: 16:9, collection the artist © Dean Cross

(image 10) Lloyd Frederic Rees ‘The road to Berry’ 1947, oil on canvas on paperboard, 34.6 x 42.2 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1947 © A&J Rees, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 11) William Yang ‘Tea with the Deputy High Commissioner, London’ from the series ‘miscellaneous obsessions’ 2002, type C photograph, 35.5 x 53.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Photography Collection Benefactors’ Program 2003 © William Yang, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

(image 12) Thanakupi ‘Mosquito corroboree’ 1994, stoneware, 32.4 x 34 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Mollie Gowing Acquisition fund for Contemporary Aboriginal art 1995 © Estate of Thancoupie, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales